The Tale Of Two Hezekiahs

Co-written by: Lynn Mumma and Marlena Jareaux

Final editing by: Gina Richardson and Annora Bailey

Research by: Marlena Jareaux

note: this is about a 20 minute read, without doing a dive into the images and links that are included.

Trying to piece together the story about someone from the 1800s can be both rewarding and frustrating. The record-keeping systems of the time were not as accurate and therefore not as reliable as we’ve come to expect them to be in this century. In researching Hezekiah Brown, we began with the writeup found on the Maryland State Archives website, which stated that he was from Calvert County. However, the only Hezekiah Brown we found in Calvert County was 60 years old and living with a white household according to the 1850 census. The Hezekiah Brown we were seeking was a teacher in Howard County 34 years later, so we kept looking. Our search unearthed the pieces of two other fascinating lives, and what follows is the story of two Hezekiah Browns. It is our hope that it both informs and engages you. Maybe some parts of it will even surprise you!

Subject 1: Rev Hezekiah M. Brown:

an extraordinary man who was deeply committed to educating African Americans at a time when so many were not.

Childhood

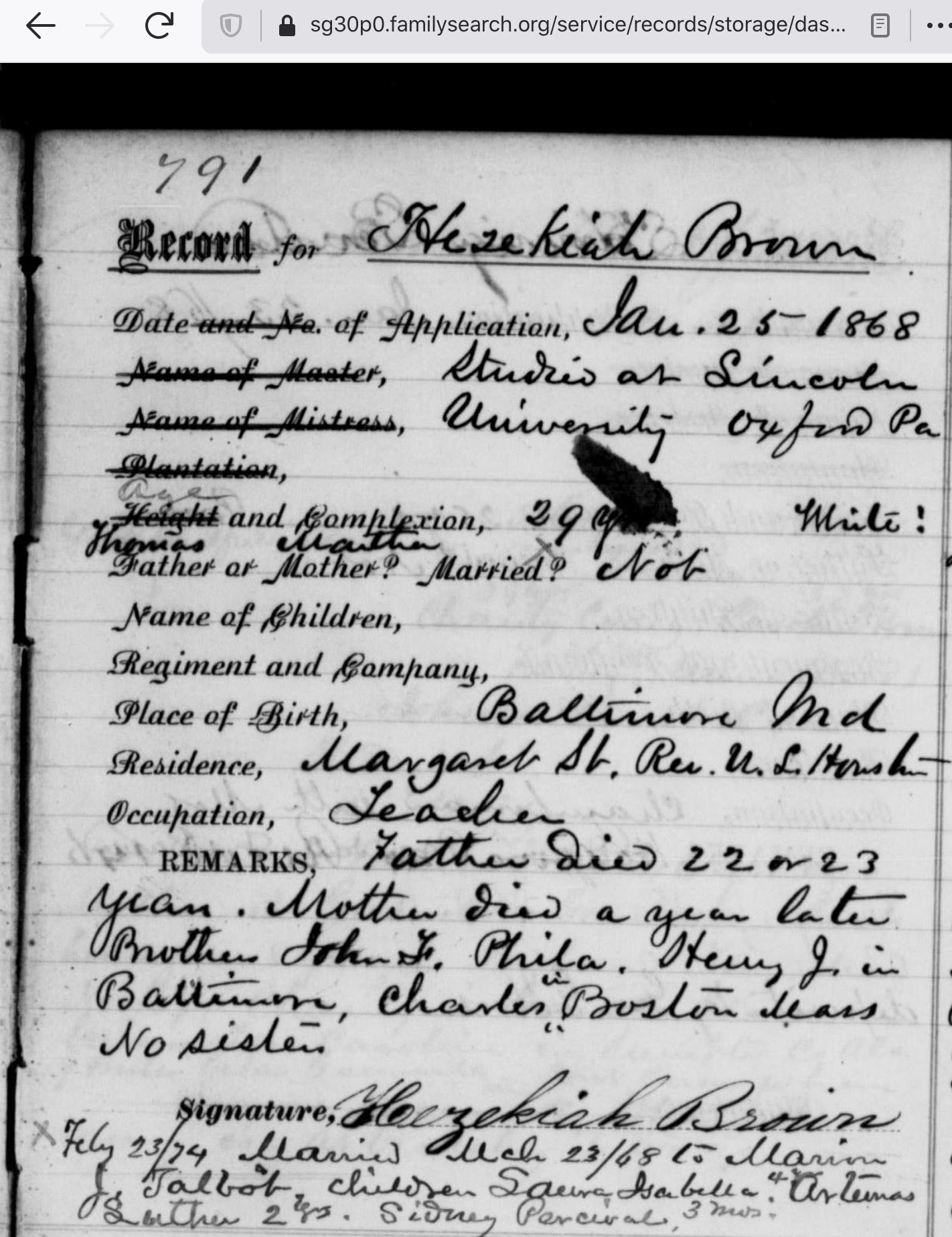

This Hezekiah’s precise year of birth is unknown but was most likely around 1837-38. His father’s name was Thomas Brown, and his mother was named Margaret. Nothing is definitively known about the lives of either of them. Documents consistently identify Hezekiah’s race as being “mulatto,” with references to him having been very light-skinned.

The above bank record lists Baltimore, Maryland as Hezekiah’s place of birth, and Pennsylvania as where he grew up. If the bank record is interpreted as his father having died 22-23 years prior, he would have died around 1846, with Hezekiah’s mother dying the following year. This means that Hezekiah had lost both of his parents by around the age of 10.

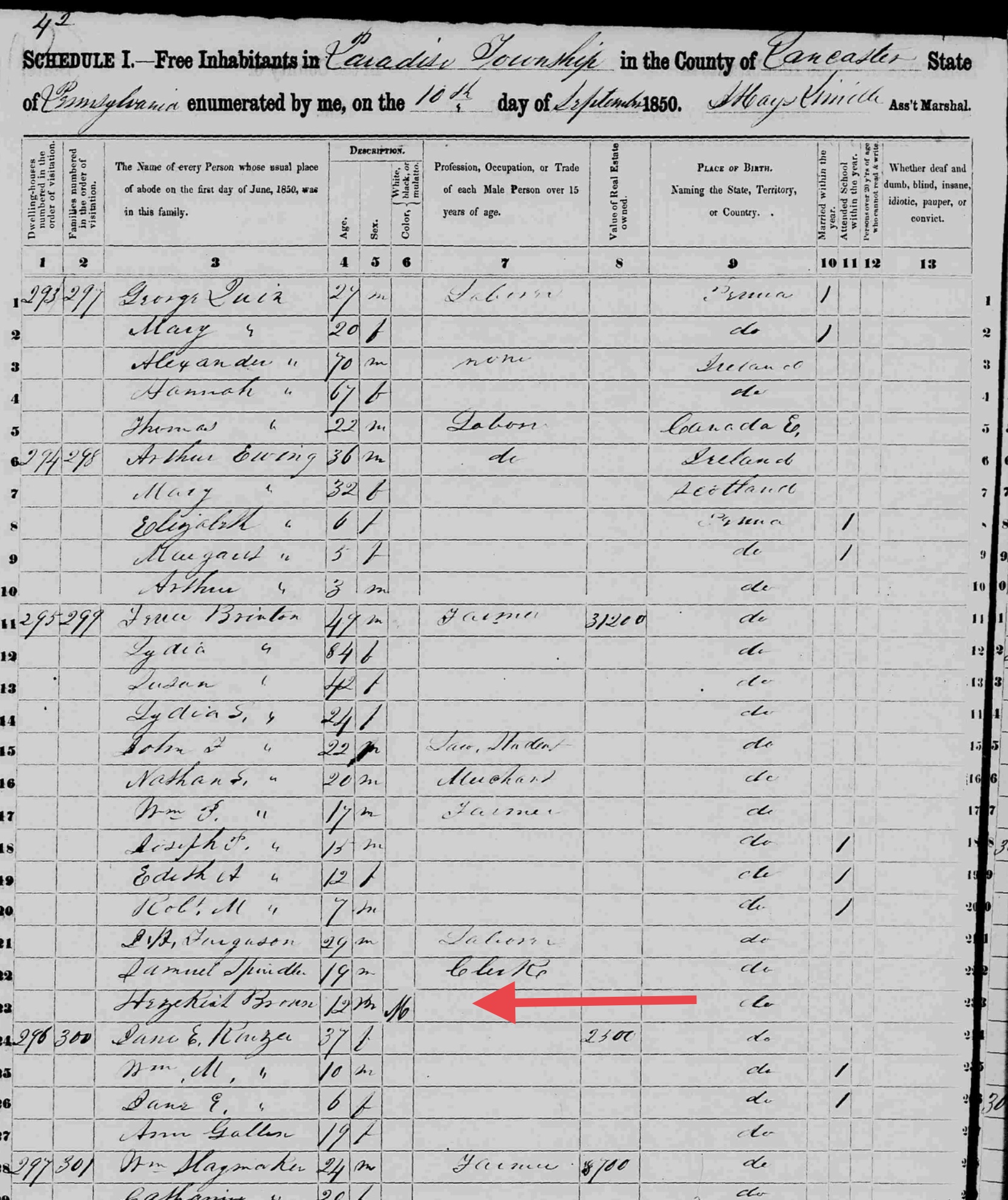

The below 1850 census document lists Hezekiah Brown, mulatto, age 12, living in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania with the family of Ferree Brinton, who was a judge and farmer. According to the census, Hezekiah was not enslaved. He was listed as being free, as was the rest of the household.

Hezekiah is recorded on bank records as having at least four brothers (John F., Henry J., Alexander, and Charles). He also had a sister (Selina), whom he reported in 1871 as having died, as had Alexander.

However, none of these siblings lived with him in the Brinton household in 1850. If this is the same Hezekiah, which is likely given what we know about his age and where he grew up, he spent at least some part of his childhood living in a white household, separated from his family. We do not know how or why he came to live in the Brinton household. We also do not know if it was with the blessing or knowledge of his parents. We do know from the census that whereas the Brinton children were enrolled in school, Hezekiah was not. This would soon change.

Early Adulthood

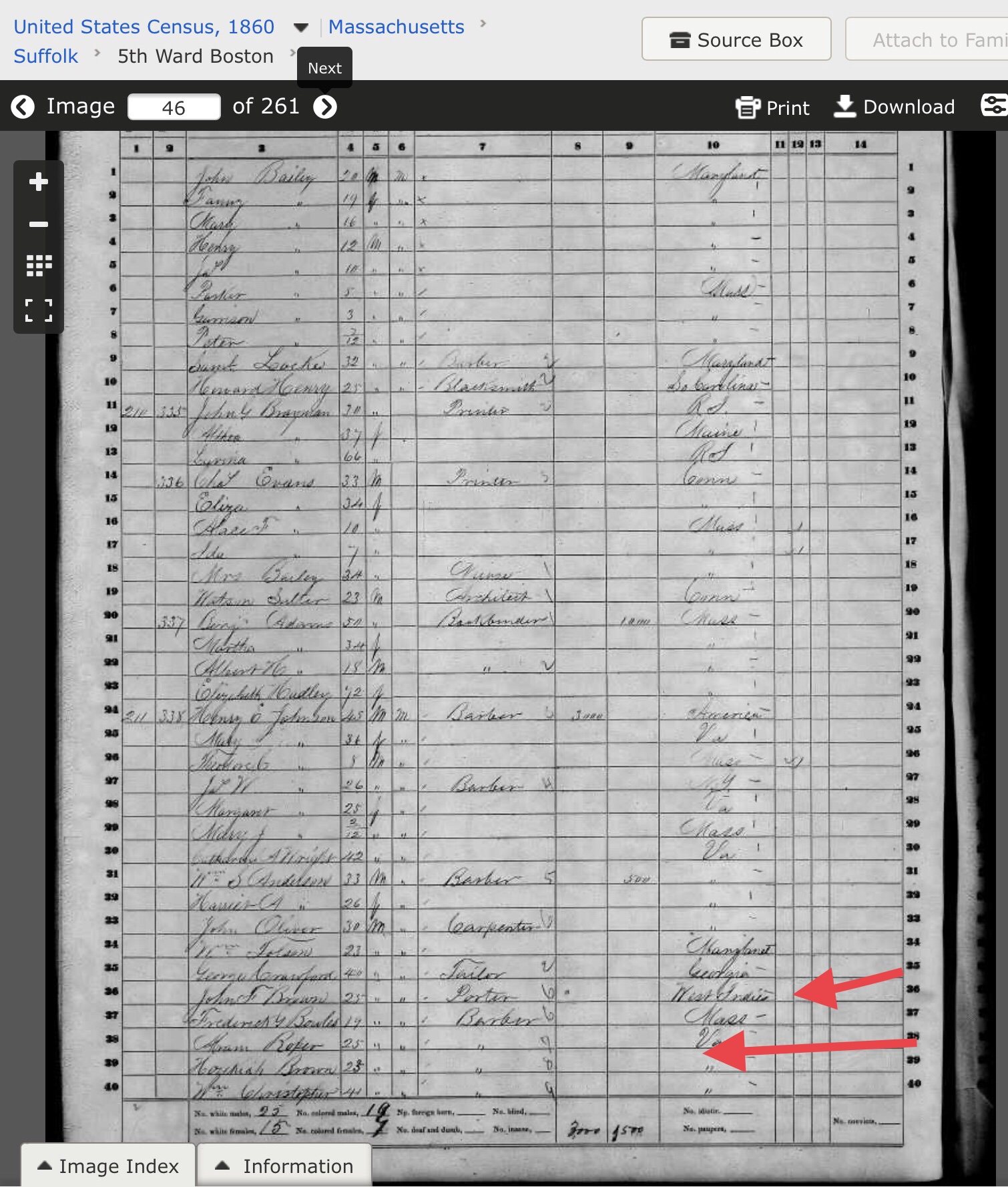

In 1860 there was a Hezekiah Brown living in the 5th Ward of Boston, Massachusetts in a household with several other African American young men (most labeled as “mulatto” by the census taker), including John F. Brown. As this was the name of Hezekiah’s older brother, we assume it is the same Hezekiah. John’s occupation was listed as porter, and Hezekiah as barber. They were living in an interesting community, with printers, a bookbinder, and an architect living in nearby households. Interestingly, John B. Bailey, who was a somewhat famous African American, lived nearby. John was born free in Maryland. His occupation was listed as a teacher on the census, but he was so much more. He owned a gym and pistol gallery and what he “taught” was self-defense!

Education

Hezekiah subsequently returned to Pennsylvania and was a student in the Theological Department at Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania during the 1865-66 and 1866-67 terms. The 1866-67 university catalogue lists him as being from Philadelphia, PA.

Lincoln University (originally Ashmun Institute) was founded in 1854 as a college and theological institution for men of color. It had three departments (Theological, Academical, and Preparatory). One of its Trustees, General Oliver O. Howard, played a role in forming Howard University in Washington DC. Gen. Howard was also the first Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which helped to set up educational systems for African Americans after the war was over. An interesting note is that another student, James R. Dorsey, was from Ellicott’s Mills, MD, which is located in what is now Howard County, where Hezekiah had family roots. It isn’t known if the two young men knew each other prior to attending Lincoln. Alexander H. Brown from Hollidaysburg, PA, was another fellow student. It is possible that this was Hezekiah’s brother. Also of note: the catalogues were printed by the press belonging to H.L. Brinton. It is conceivable that he was a relative of Judge Brinton.1

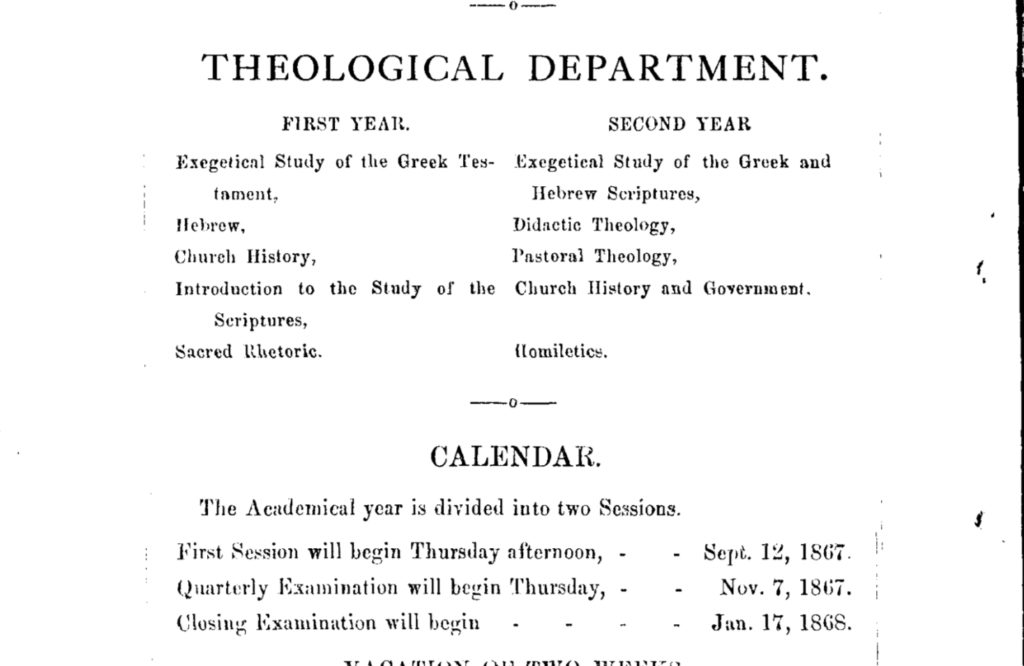

The 1865-66 catalogue does not indicate the specific program in which each students was enrolled, but the studies for Hezekiah’s 1866-67 year would have been one of the following curriculums:

Lincoln was known to be a school that supplied teachers to the South. Meeting minutes of its Board of Trustees reflect that the Faculty’s Annual Report, dated June 19, 1867, states that “several Associations for the moral educational advancement of the Colored People are asking for teachers from this Institution for their schools in the South. We could secure renumerative situations for more than forty teachers, in Sept next, if we could supply the men.” (Source found pg 72 HERE)

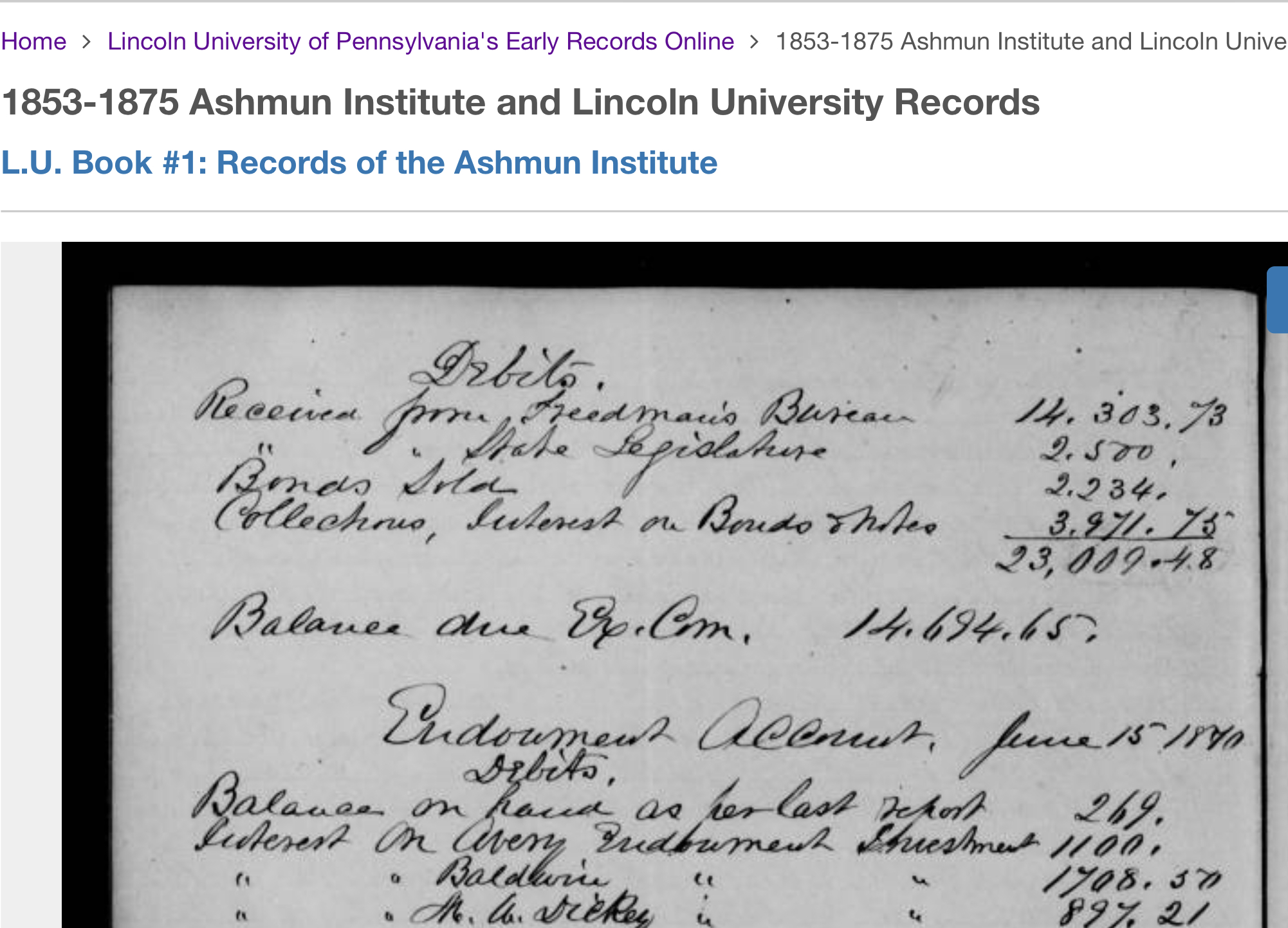

The Freedmen’s Bureau paid monies to Lincoln University:

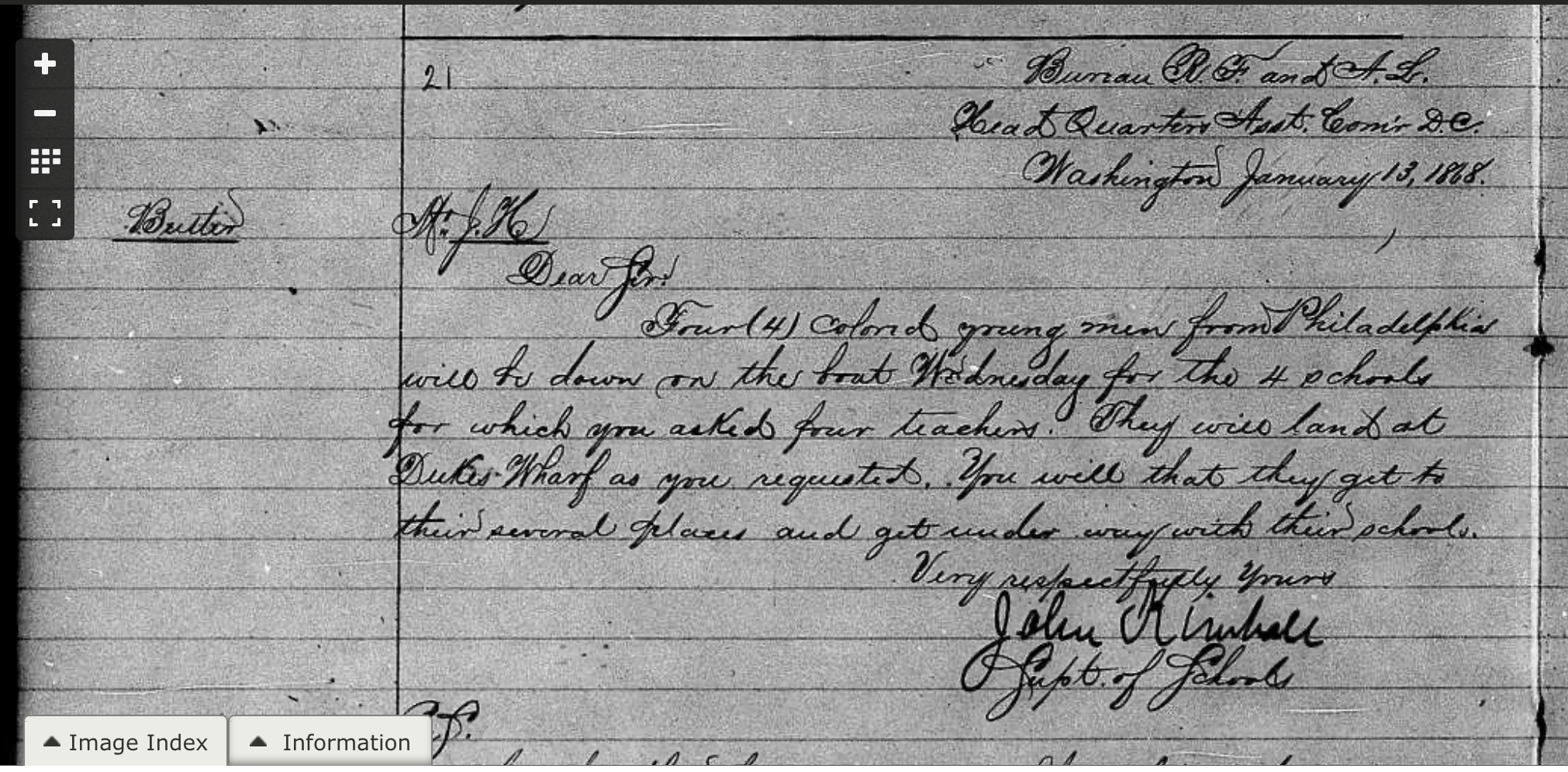

It seems that Hezekiah became one of the teachers who went south to teach. The 1868-69 Lincoln catalogue lists Hezekiah as being a senior in the academic part of the college and having moved to Savannah Georgia.

Hezekiah Moves to Savannah, Georgia

In 1868, Hezekiah was 29 years old and lived on Margaret Street in Savannah. At that time, he reported that his brothers were living in Philadelphia (John), Baltimore (Henry), and Boston (Charles). In March 1868, he was teaching at a school that was referred to as “Brown’s School.” It opened in January 1868 with 15 female and seven male African American children. The number of those students who had been free before the Civil War, as reported by Hezekiah, was zero.

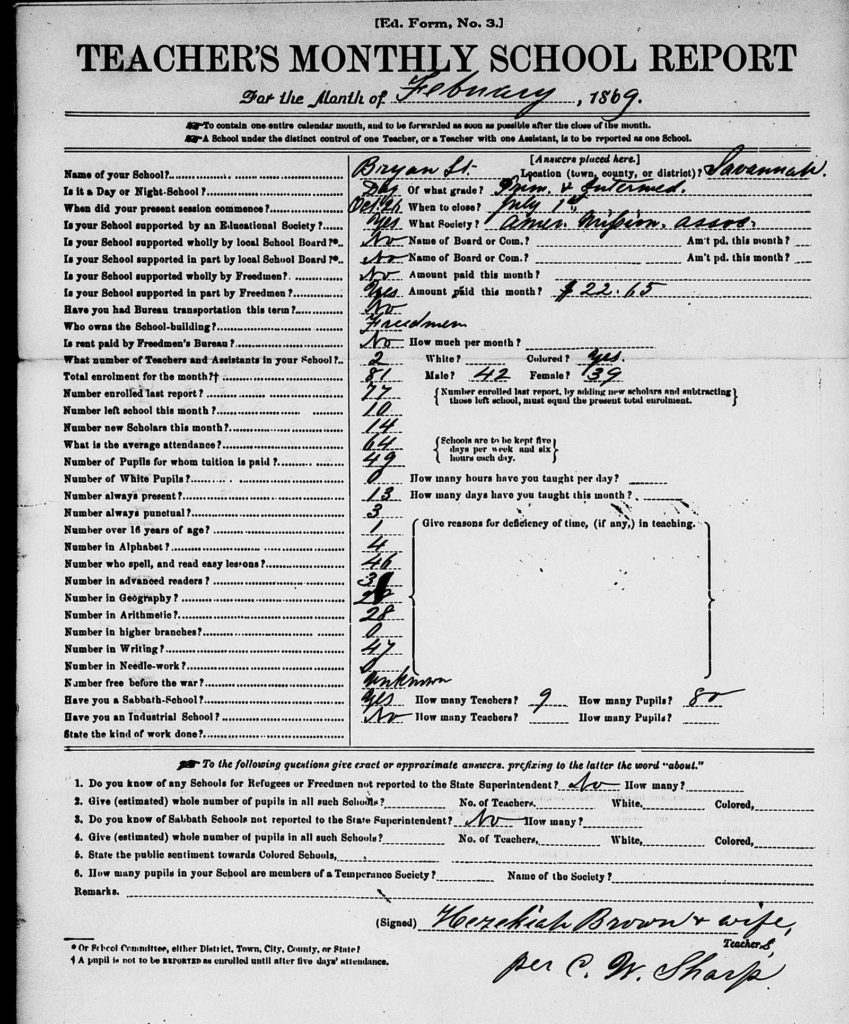

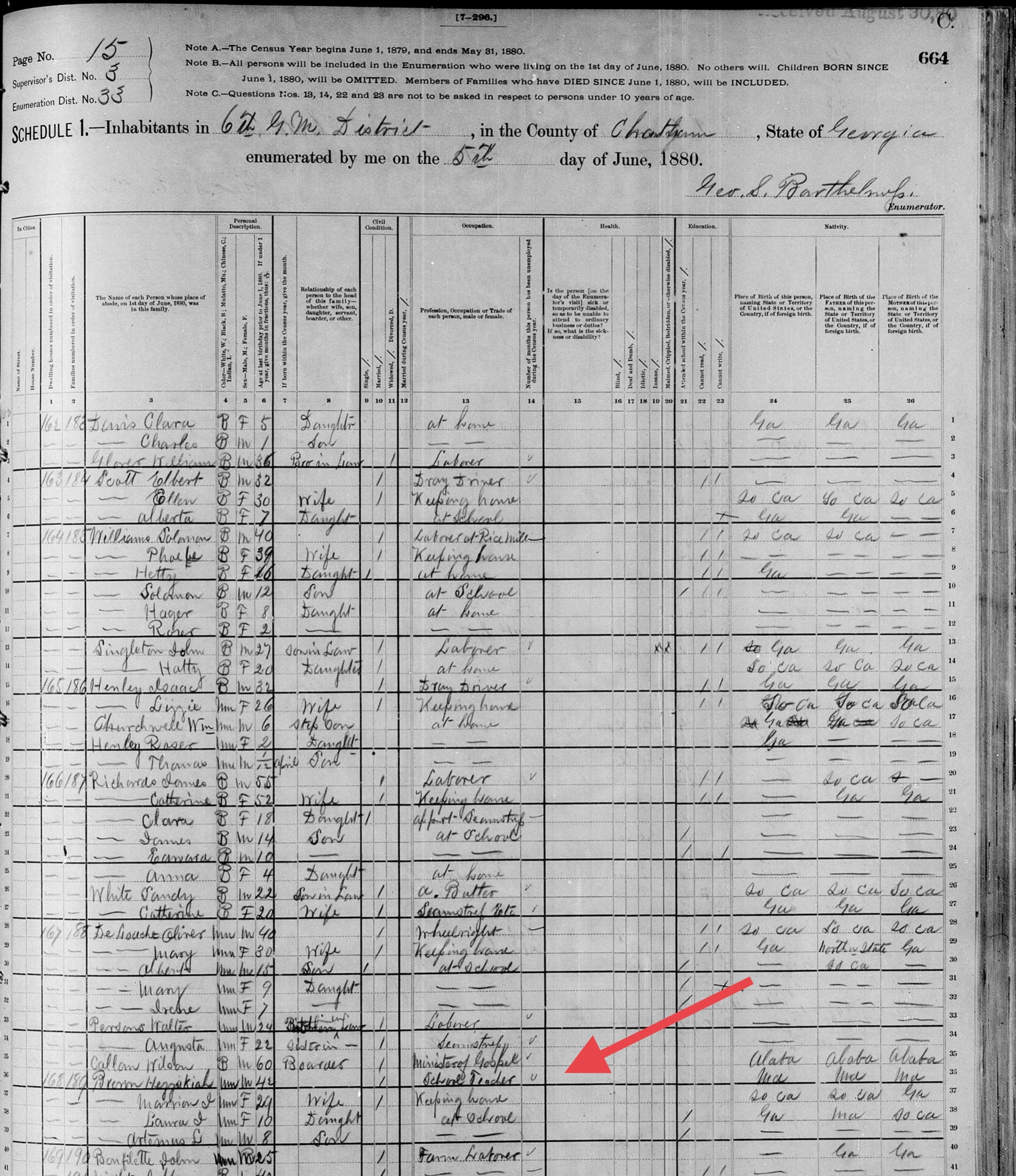

Hezekiah married Marion J. Talbot on March 23, 1868. School reports indicate that he and his wife were teaching 39 female and 42 male primary and intermediate African American students at the Bryan Street school in Dec of 1868 and February of 1869. The Bryan Street school was likely located in what had previously been the Bryan Slave Mart, which had been known as the Montmollin Building. This was one of many buildings and parcels of land that were confiscated from Confederate sympathizers and converted into buildings for public uses following a meeting in Savannah in January 1865 between Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War, Major-General Sherman, and a group of leading African Americans. One purpose of the meeting was to discuss how the newly freed people could take care of themselves and “assist the Government in maintaining [their] freedom.”2 After being confiscated, the top floor of the Bryan Slave Mart was turned into a school for freed slaves and their children.3 An 1895 pamphlet regarding schooling of African Americans in Georgia also confirmed that the building was turned into a school.4

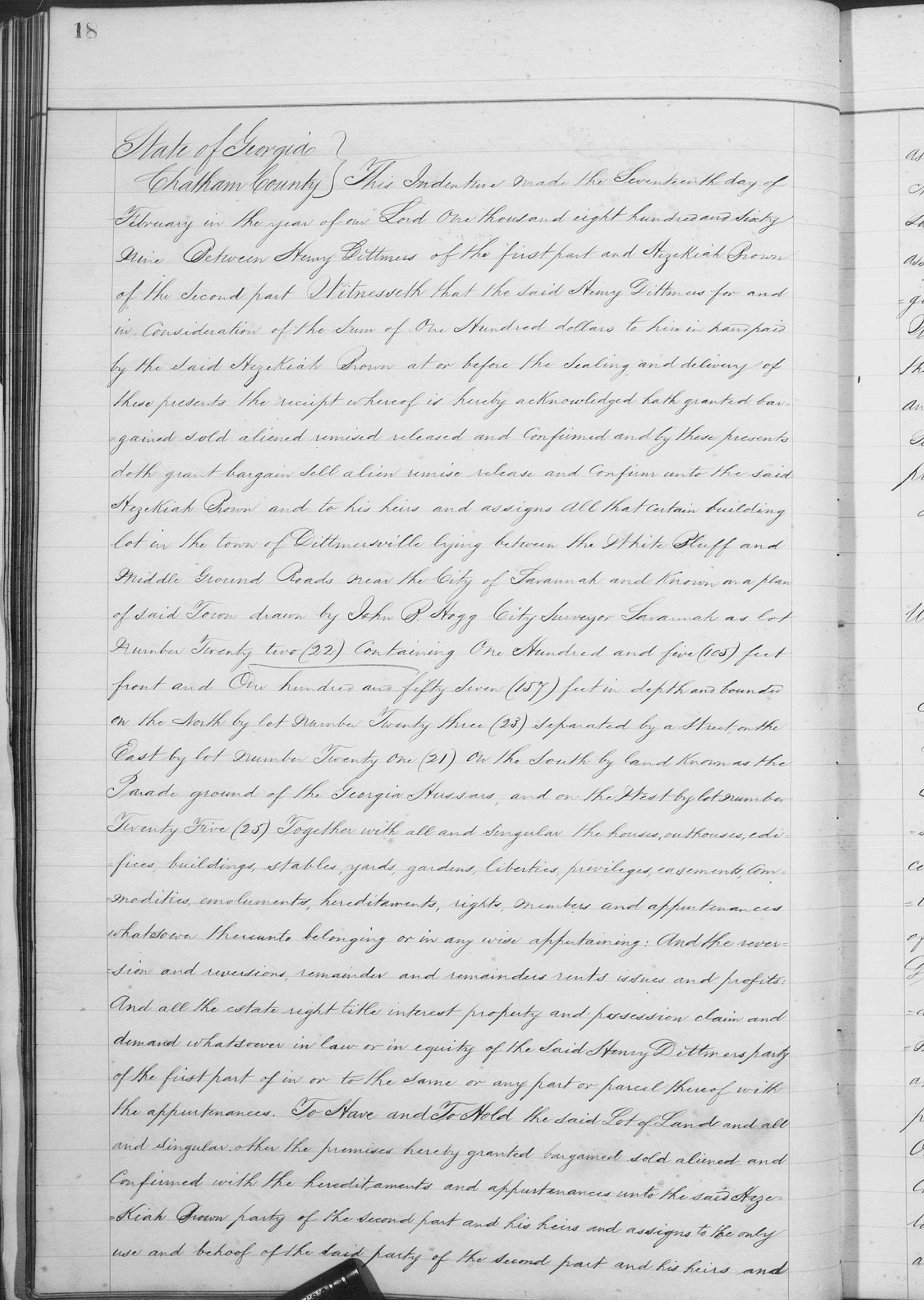

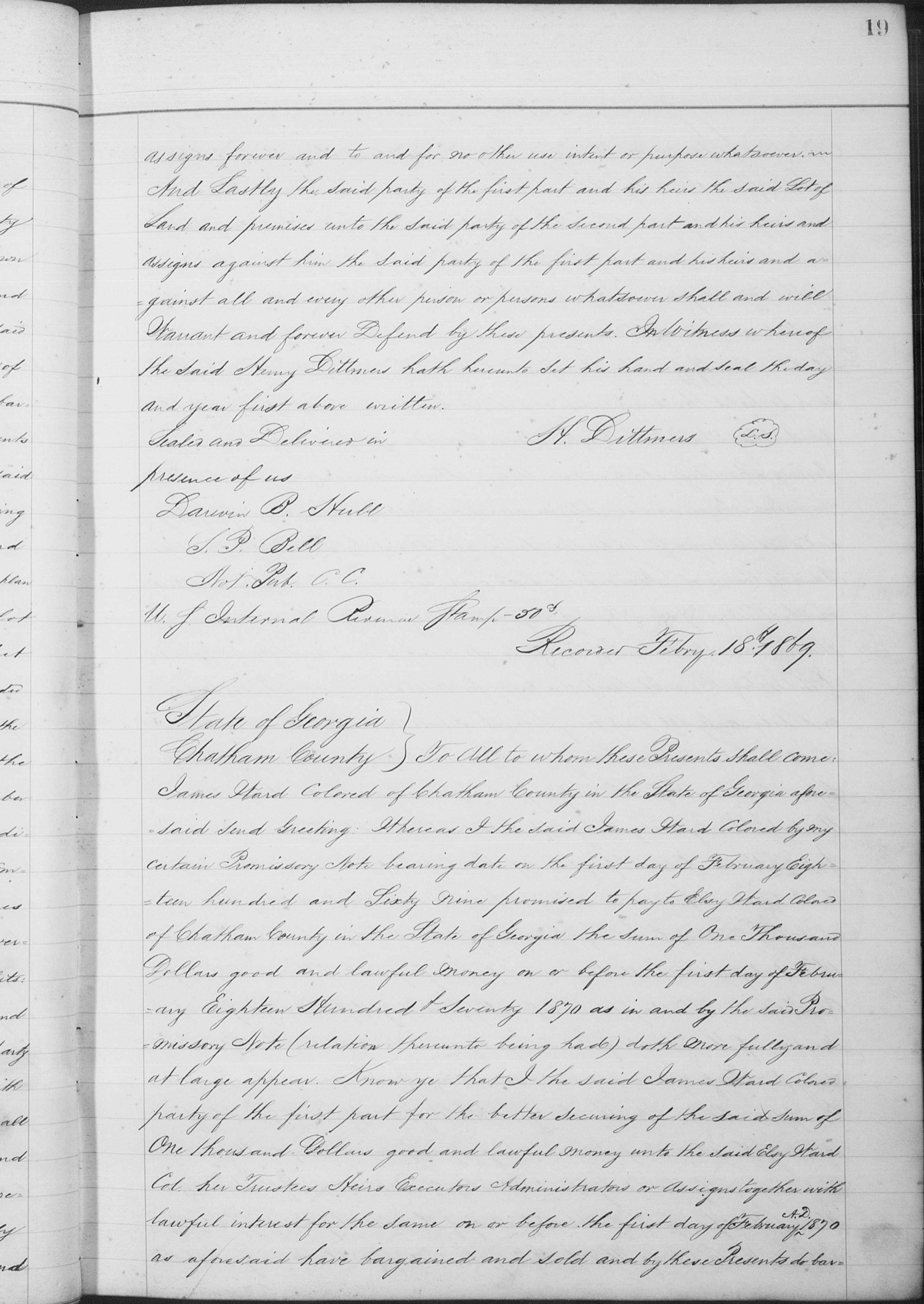

Hezekiah purchased his first property (Lot 22) in Dittmersville, Chatham County, Georgia on February 17, 1869. He and Marion had their first child, Laura Isabella Brown, later that same year. On their January 1870 Teacher’s Monthly School Report, he and Marion reported that “we have a school House in erection when it is finished we shall establish a Sabbath School.” It is possible that the school they referenced was being constructed on Hezekiah’s land.

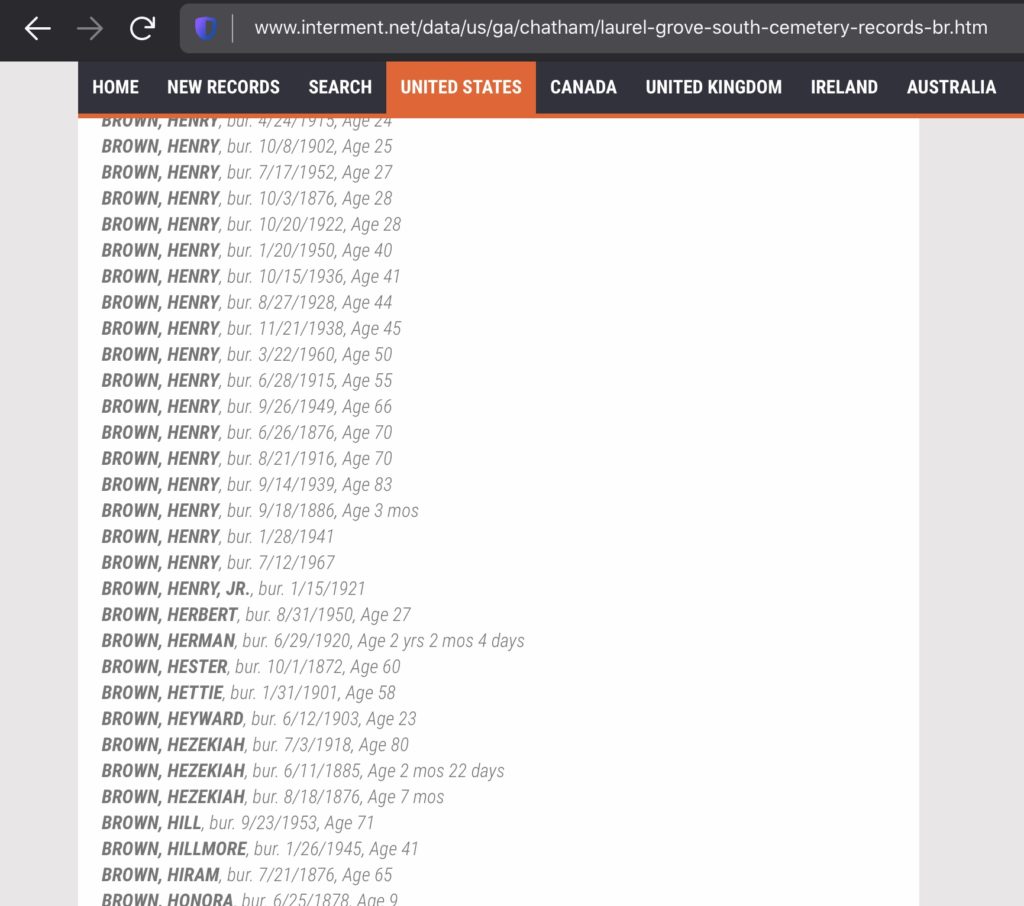

On April 6, 1873, Hezekiah purchased Lots 23, 24, 25 and 26 of Block 1 in Dittmersville, Chatham County, Georgia for his growing family. By February of 1874, the family included Laura Isabella (age 4), son Artemus Luther (age 2), and Sidney Percival (3 months). (This information is indicated at the bottom of the 1868 Freedmen’s Bank record above). As was common, he and Marion may have had a son whom they named Hezekiah. If so, this son died as an infant on August 18, 1876 at age seven months. He was buried in the Laurel Grove cemetery, in the African American section.

Public Education in Maryland

As the Civil War was coming to an end, the Maryland legislature began working to improve education throughout the state as one important strategy to heal from the divisions of the war. Schools existed in Maryland prior to the war, but there had not been a uniform statewide public education system. In 1867, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction submitted the first Annual Report, dated 1866, to the General Assembly. It was reported that there were 73 schools for the “colored” population, with 22 being in Baltimore City and 51 in 19 of Maryland’s counties. However, schools for African American children were grossly underfunded. An 1868 Maryland law entitled “Public Education” (Chap. 407) provided that white youths between the ages of 6 and 18 would be educated for free.5 In the “Colored Population” section, it stated that the “Total amount of taxes paid for school purposes by the colored people of any county, or in the City of Baltimore, together with any donations that may be made for the purpose, shall be set aside for the maintaining the schools for colored children.” This was to be done under the direction of the Board of County School Commissioners, which had the power to appropriate funds that “…in their judgment they may deem proper to further assist the schools for colored children.” Thus, whether or not to fund public schools for Black children, and if so at what level, was left a choice. In the December 8, 1870, edition of The New National Era, the National Teachers’ Association reported that the only governmental jurisdiction in Maryland that was educating Blacks was Baltimore City.

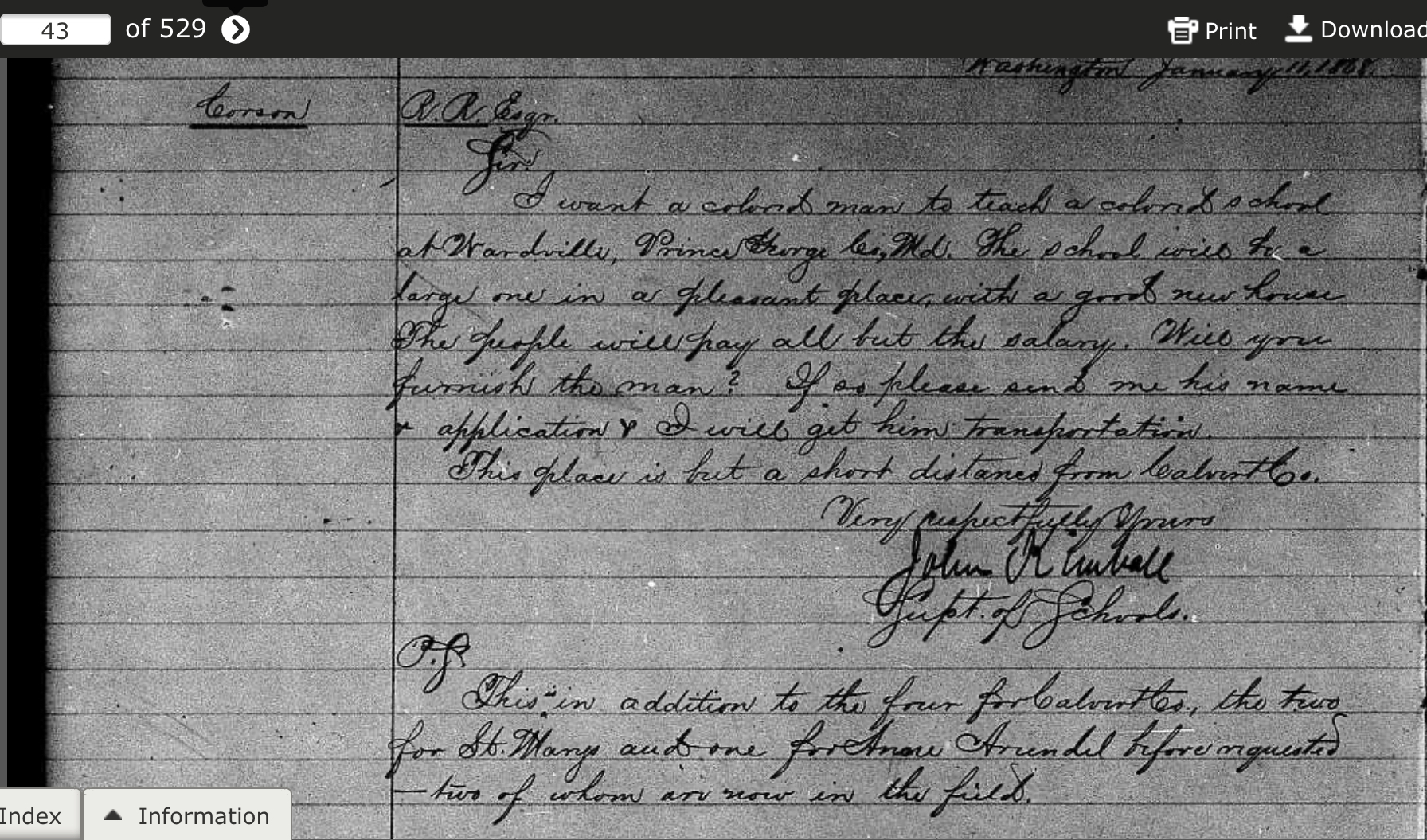

The Baltimore Sun reported on March 19, 1869 that Rev. John Kimball, who was the Superintendent of Education under the Freedmen’s Bureau for the district that encompassed the District of Columbia and Maryland, was being sent to Anne Arundel County in order to survey existing schools for the Bureau and open new ones. The Bureau had created field office locations in Annapolis, Bladensburg and Rockville to support educational initiatives and assist with disputes regarding labor and Maryland’s apprenticeship practices.6

In 1872, the General Assembly passed legislation that changed the age range for the free education of white youths to “over six and under twenty-one”. (Chap 377, Act of 1872, Chap IX, Sec 1).7 It also mandated in Chap XVIII that “one or more public schools in each election district for all colored youth between six and twenty years of age” be created. These schools were also to be free. This legislation was the result of several years of intense advocacy efforts to mandate free public education of Black children. However, in regard to paying for it, the General Assembly again left it up to “such a manner as to said Board of County School Commissioners may seem best.”8

As was the case across much of the country, the Black population of Howard County had to fight long and hard for equal access to education after the end of the Civil War. By 1865 the Howard County Board of School Commissioners had formed. After assigning districts and schools to the respective Commissioners, one of its first pieces of business was to set salaries. This happened during a meeting on September 5, 1865. Not until June 7, 1870 is there any record in the Board’s minutes of the county’s African American population. It was recorded on that date that the Commissioners wanted to have a report compiled to determine the amount of levy (taxes) paid by the “colored” population of Howard County into the school fund.

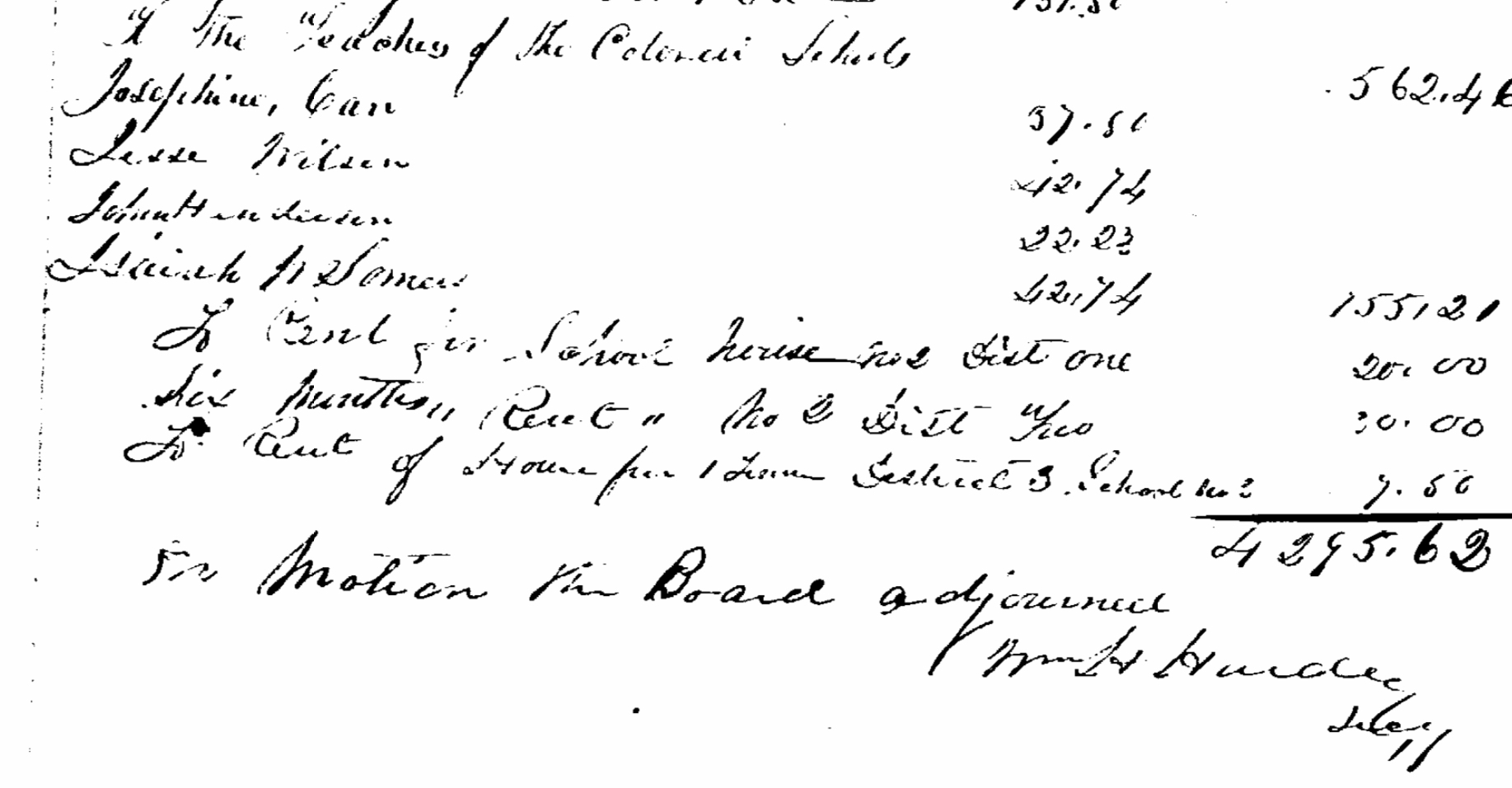

On April 26, 1873, a note was made in the Board Minutes of the monies given to teachers “of the colored schools”. The race of these teachers is unknown.

*from the Howard County MD Board Of Education archives9

On August 15, 1878, the Board decided to close five of the schools that served “colored” children and maintain only one in each election district. According to Board minutes, a “petition of the colored population living near what is known as Free Town in the Fifth District” for a school was granted in October of 1878. The Examiner was ordered to open a school there after the end of the Fall term, to continue for 2 terms or until April 15, 1879. In June of 1879, the Board Secretary was ordered to select and purchase a site for a colored school in the 2nd District in or near Ellicott City. In September of 1879, it was decided that the Colored School Fund, which included local tax assessments and state funds, would be used for the purpose of building that school.

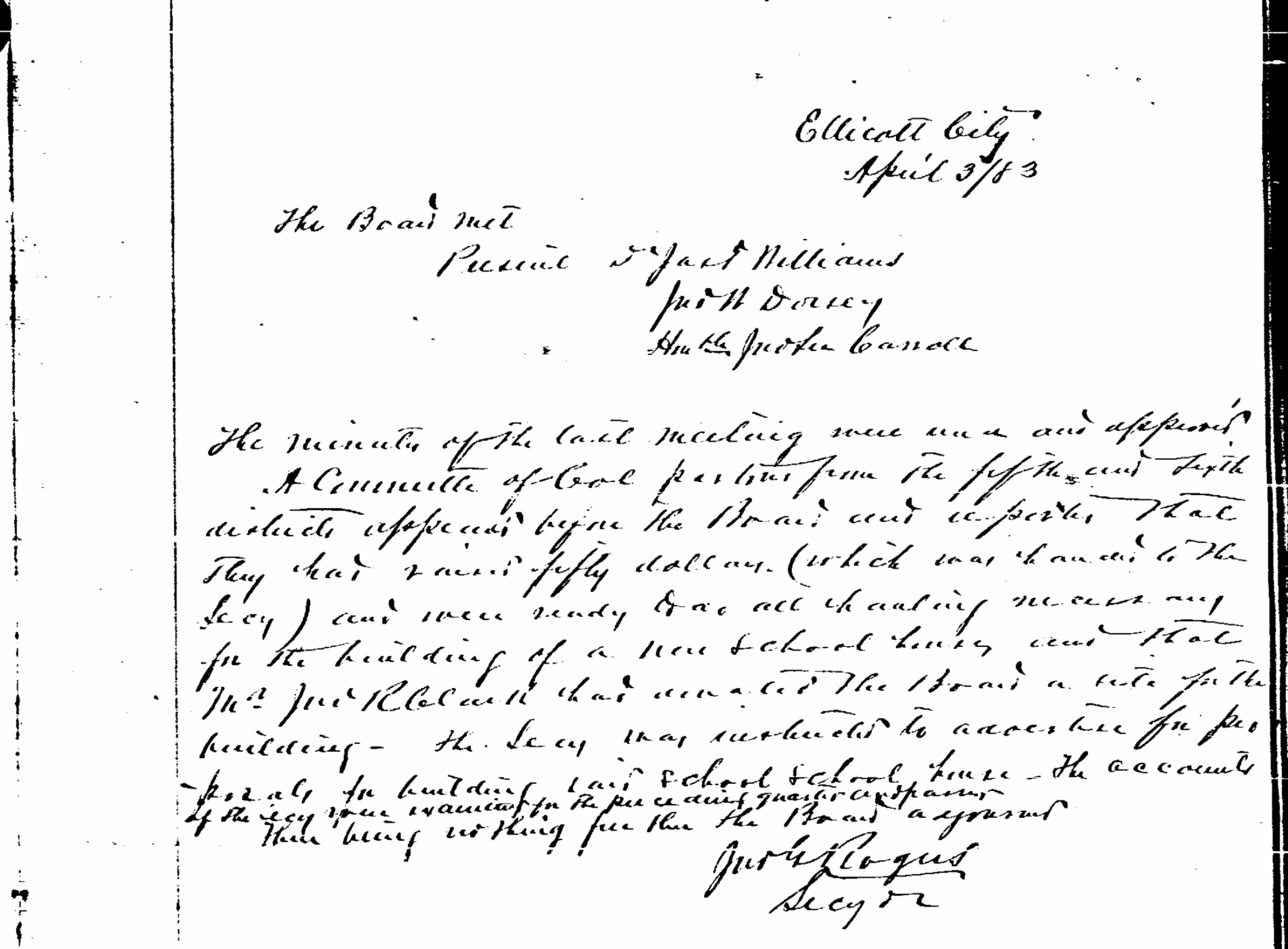

On October 17, 1882, a petition from “colored citizens from [the] Sixth District asked for erection of a building near FreeTown in 5th District.” The Board rejected it as being “inexpedient at present.” On November 9, 1882, a petition was again made for a school by “colored persons living near Free Town in 5th District”. The Board decided to hire a teacher and open a school “for two terms” only. During the April 3, 1883 Board meeting, it was noted that a “Committee of Col parties from the fifth and sixth districts appeared before the Board,” handed a sum of money to the Secretary, and said they wanted a school built. A man by the name of Mr. Colwell was said to have land he would donate for it.

On September 4, 1883, a “Committee of Germans” asked the Board to erect a school for their children, which was declined by the Board due to a “failure of sufficient reasons”. During the same meeting, a “Commitee of Col persons” from the 1st, 4th and 6th districts petitioned the Board for additional facilities. The residents of the 4th district said they would raise $200 for it, but the Board declined. (Pg 189 of the Minutes) During the October 7, 1884 meeting, Trustees for the Colored schools in each election district were finally appointed.

Was the Georgia Hezekiah in Howard County?

There are records indicating that Rev. Hezekiah M. Brown had family roots in the Maryland area, but we have not found documents confirming that he returned to the area. It was possible to us that Hezekiah, who trained as both a teacher and a man of the ministry, came to help the Freedmen’s Bureau advance educational opportunities for African Americans in Howard County after the war, which were very limited at that time. The Freedmen’s Bureau records document its work in neighboring Anne Arundel County and its efforts to bring African American teachers from Philadelphia to Maryland. It is possible that those teachers would have been educated at Lincoln University. The Bureau assisted with opening schools in Calvert, Alleghany, PG, St Mary’s and Montgomery counties, with a school as close as Laurel.10

An 1880 census shows that Hezekiah was still living in Chatham County, Georgia, along with Marion and his children, Laura and Artemus. Sidney P. Brown had died at the age of 1 year and 7 months on August 17, 1875 and is therefore not listed. Sidney is interred at the same cemetery as baby Hezekiah.

It was possible to us that Hezekiah, trained as both a teacher and a man of the ministry, came to Howard County to help teach.

“Did he come to Howard County?”, was our question.

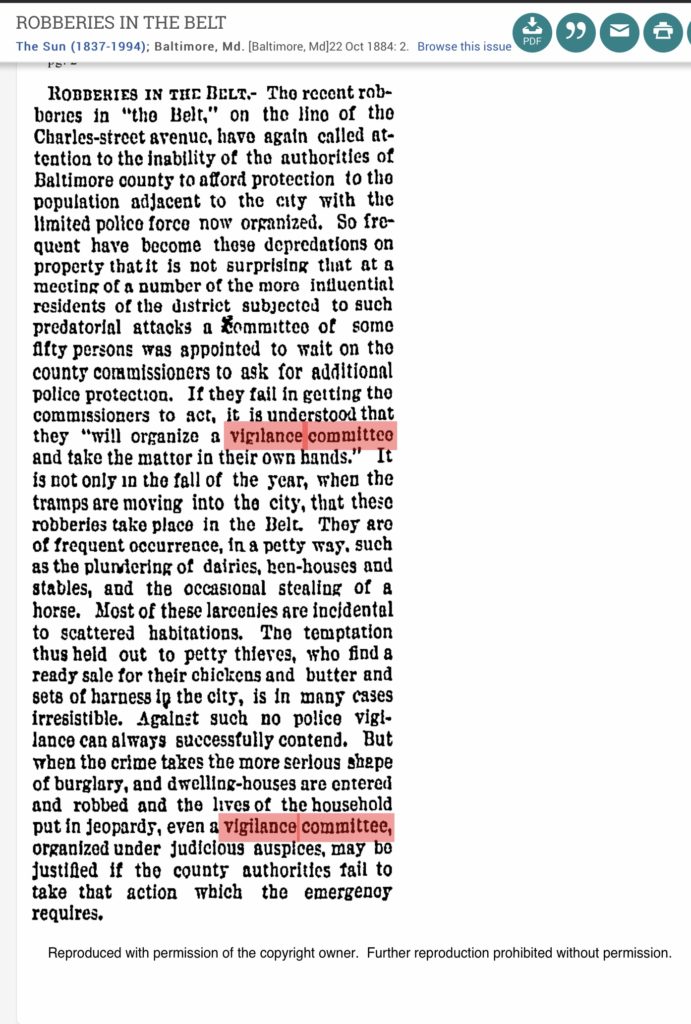

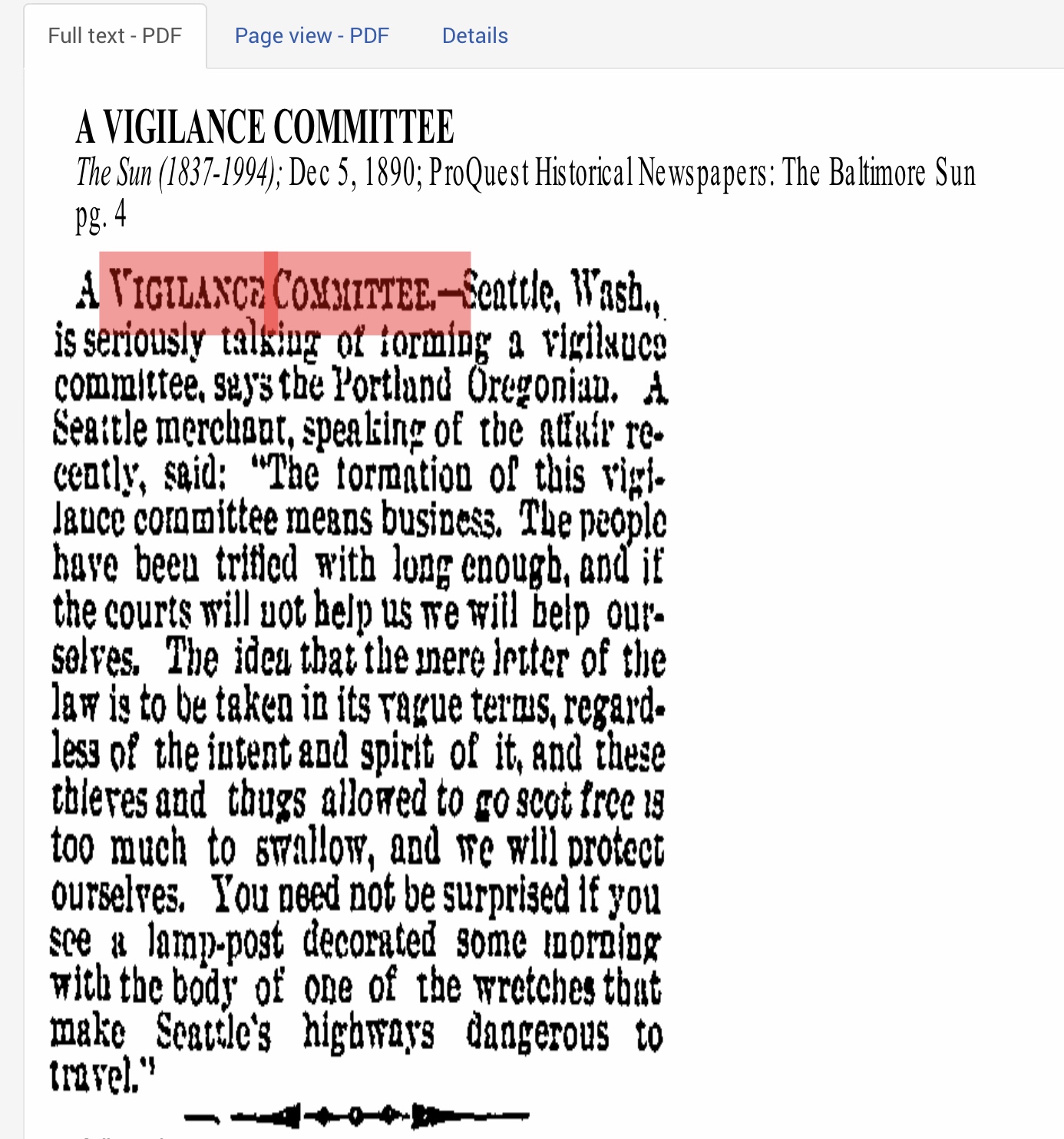

Vigilance Committees

Before moving to the next part of this story, it is important to explain the usage of the term “vigilance committee,” which was commonly used by the Baltimore Sun and other newspapers during this time. Vigilance committees or “regulators” were formed by private citizens to administer law and order outside of government structures, often for the purpose of enforcing the racial hierarchy with violence or the threat of violence. A visit from one could mean a person’s arrest or their imminent death. Here is a sample of two articles published in The Sun that reference vigilance committees (one threatens a lynching):

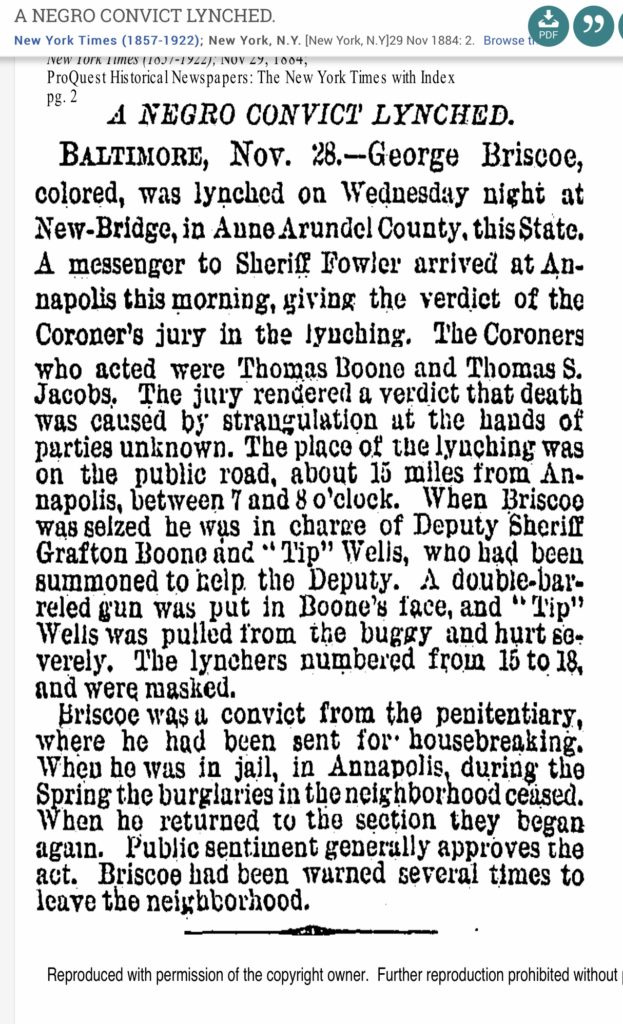

George Briscoe Lynching

To appreciate the social and political context of the events concerning Hezekiah Brown on December 12, 1884, it is important to have some knowledge of the circumstances surrounding the lynching of George Briscoe that transpired just a couple weeks earlier on November 26, 1884 in neighboring Anne Arundel County. Mr. Briscoe was suspected of having committed a series of robberies. Prior to being arrested, a “vigilance committee” visited his home at 2:00am and told him to leave the county. Someone in the crowd shot into his house. Later that same day a warrant was issued, and Mr. Briscoe was arrested. The Baltimore Sun reported that, “Briscoe’s manner and language were insulting to himself and all who were present. The man was full of bravado at all times.” While being transported to Annapolis that evening for an appearance at a higher court, near the head of the Magothy River, “more than a score of men swarmed into the road from the woods … all of whom were masked”.11

Mr. Briscoe was lynched and hung from a nearby tree reportedly within an hour.

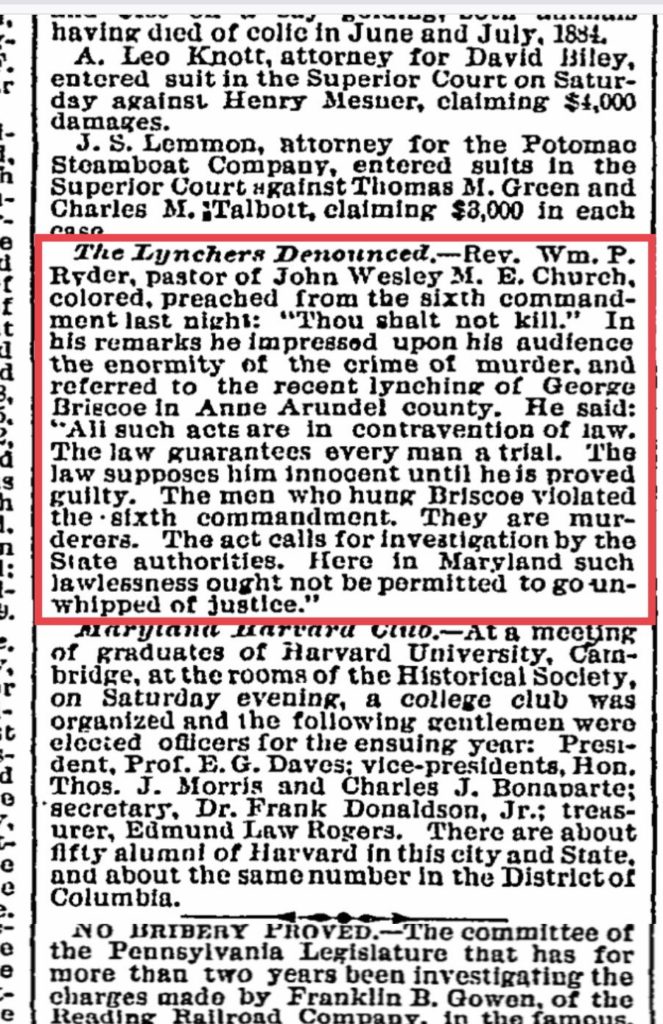

Mr. Briscoe’s lynching was reported in The New York Times on November 29, 1884. The Baltimore Sun subsequently reported on December 8, 1884 that Reverend William P. Ryder, “pastor of John Wesley M. E. Church, colored,” denounced the lynchers as murderers and called for an investigation by State authorities.

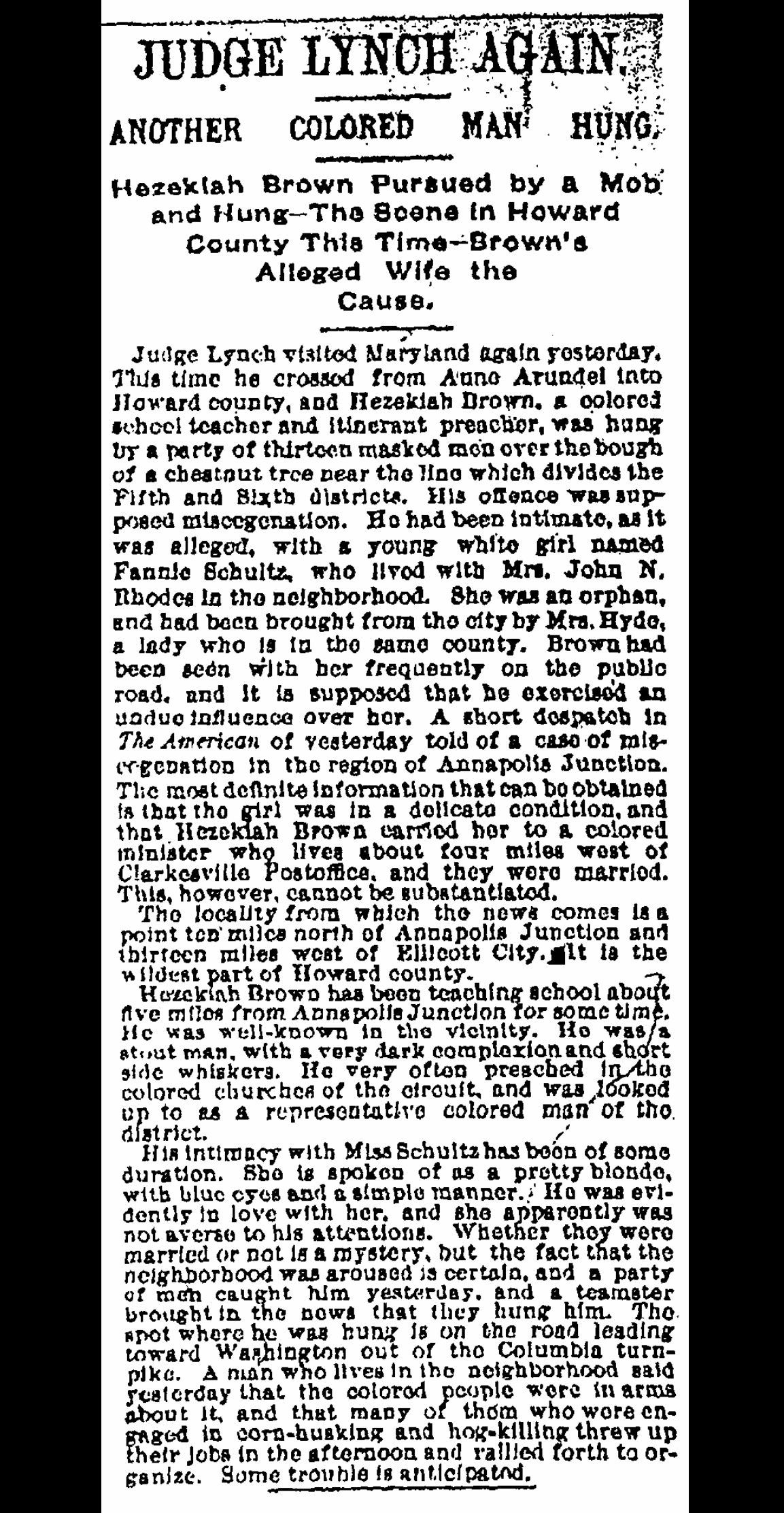

Reports of the Lynching of Hezekiah Brown

Just a few weeks later on December 12, 1884, the Baltimore American reported that the day before, a “colored man has been ordered to leave“ for allegedly marrying a white woman.12

In the days that would follow, newspapers in many parts the nation picked up the story and reported on the lynching of Hezekiah Brown.

Rather than interpreting the newspaper reports, we invite the reader to judge for themselves by reading the actual newspaper reporting on the lynching.

On December 13, 1884, the news about an event in “the wildest part of Howard County” was reported by the Baltimore American:13

The story was picked up by newspapers in other states, and was even reported as far away as Wisconsin on Christmas Day:

(Click on the image and it will open larger for you)

[dflip id=”482″ ][/dflip]

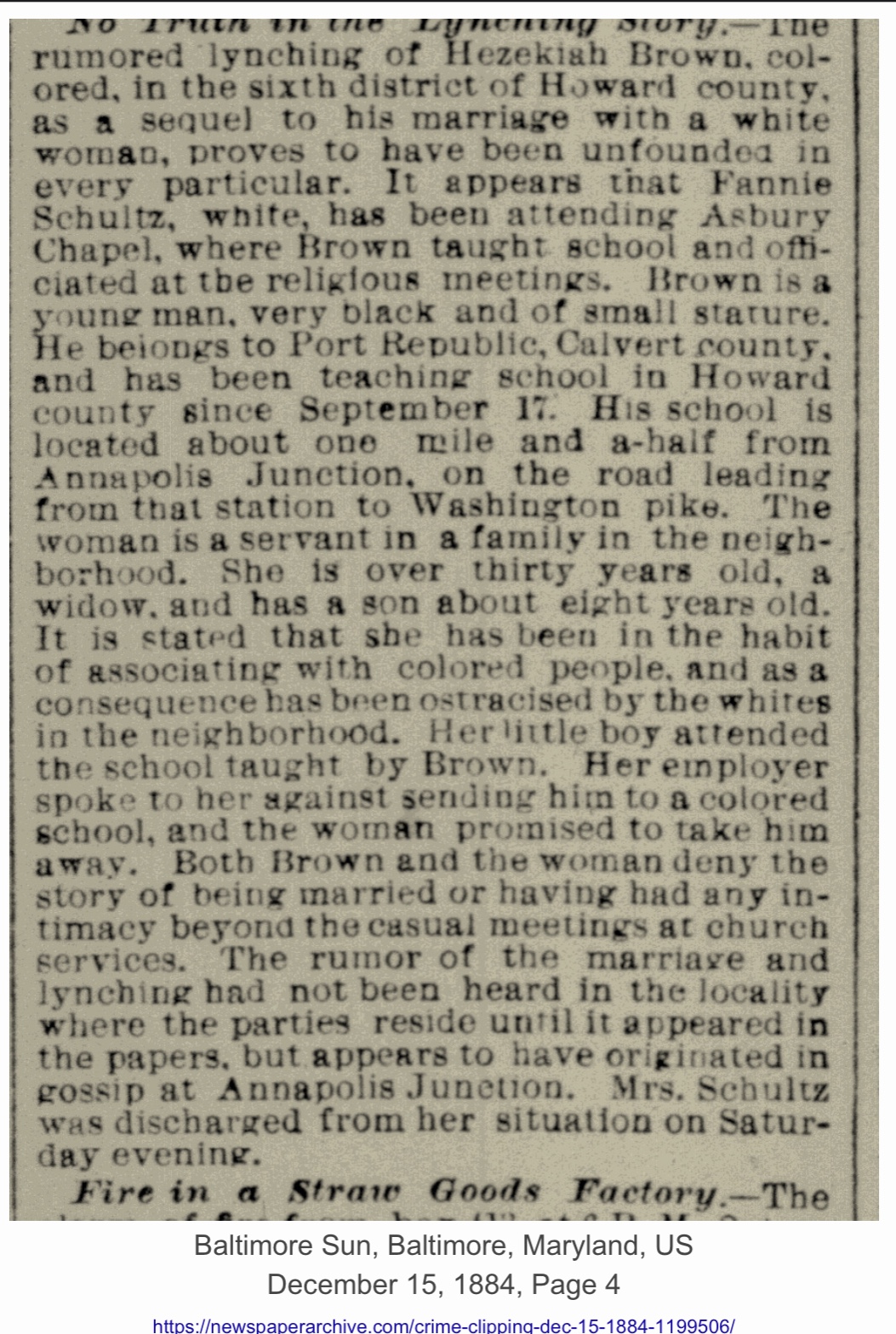

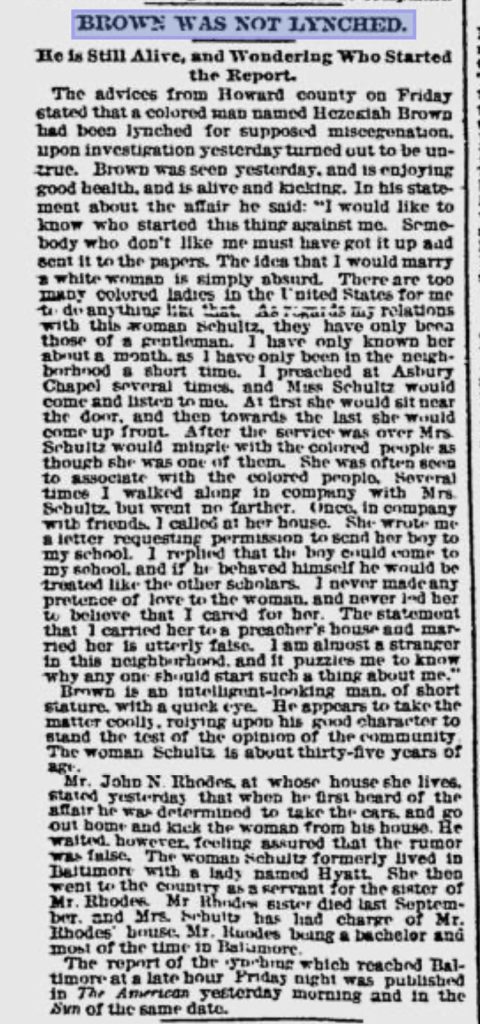

Baltimore Sun’s Retraction

The Baltimore Sun subsequently printed the following story December 15, 1884:

The Baltimore American printed the following story:14

Additional Historical Context

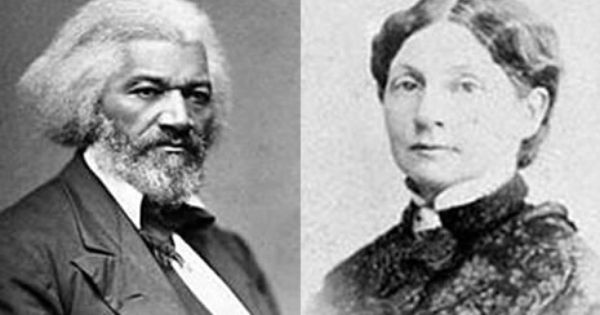

Earlier in the year that Hezekiah Brown was falsely reported to have been lynched, Frederick Douglass married Helen Pitts on January 24, 1884 in the nearby District of Columbia. Helen was a white woman.

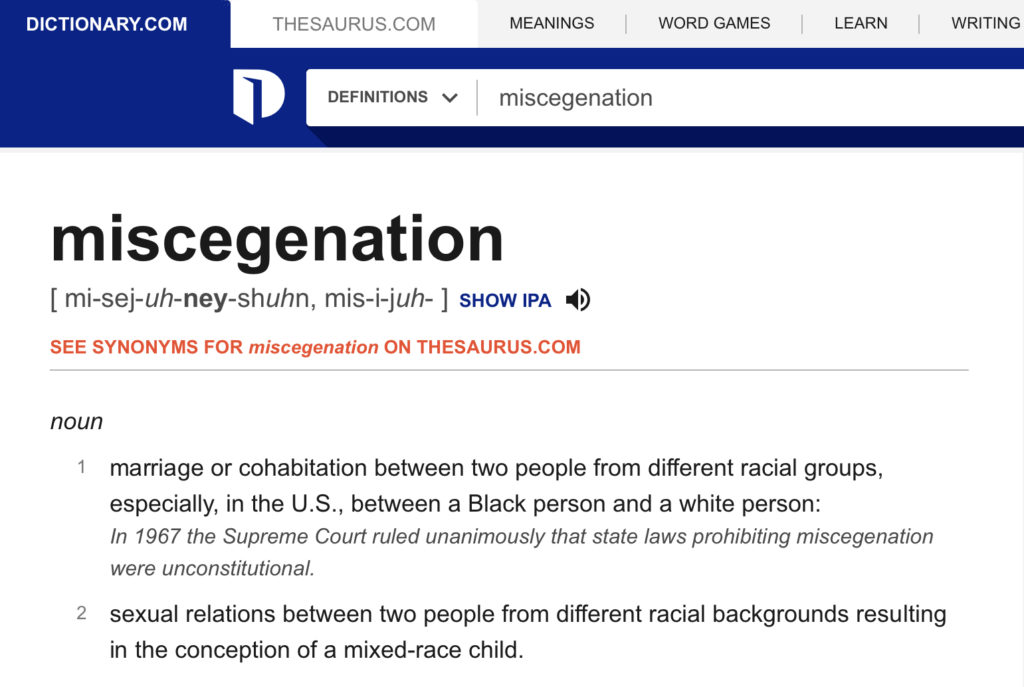

This marriage would have been considered miscegenation. It was illegal in much of the country at that time, but not in the District of Columbia.

The definition of miscegenation:

Final Reflections on Rev. Hezekiah M. Brown from Georgia

As our research about Rev. Hezekiah M. Brown unfolded, the storyline was plausible: an educated African American landowner who had been born into freedom came to Howard County to teach and was not well-received by the white community of Reconstruction-era Howard County. However, one detail did not line up: Hezekiah was already married! How did a story that a married man had married another woman gain such traction? And why was his wife Marion not mentioned in the retraction?

Subject 2:

Hezekiah Brown

We almost missed him! Rev. Hezekiah Brown: another extraordinary man who was deeply committed to educating African Americans at a time when so many were not.

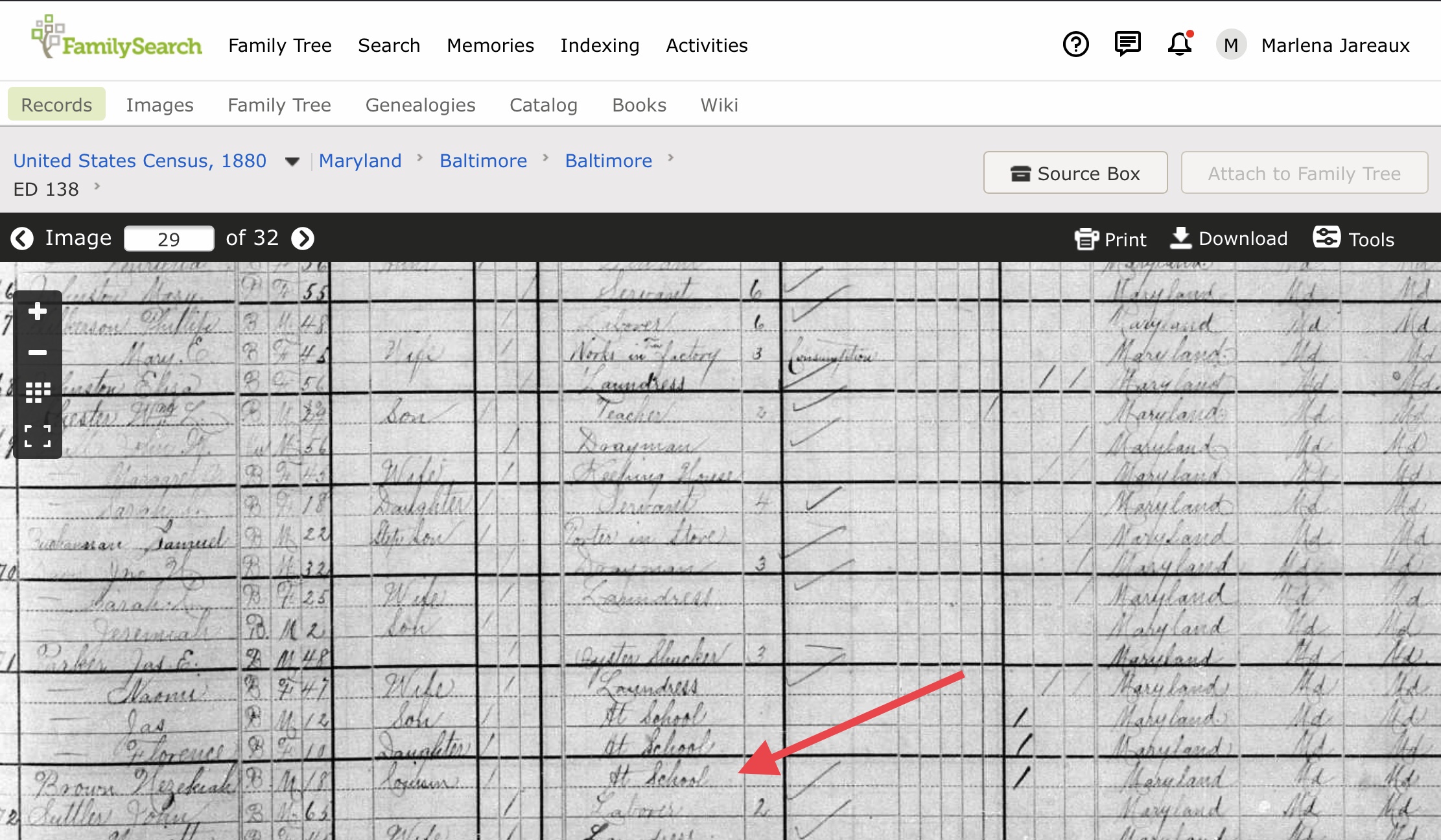

There was a “Hezekiah Brown” listed in the 1880 Baltimore City census as being “at school.” He was 18 years old at the time of the census, so he would have been around 22 in 1884 at the time of the falsely reported lynching.

The 1870 census shows Hezekiah as a young child with his parents and siblings on the 1870 of Calvert County, MD. He was listed as being 8 years old.

The 1890 census would have provided answers to many lingering questions. Unfortunately, most of the 1890 census is lost forever to history.15 However, other records from the time period did survive.

Howard County Board of Education records dating back to this era are not searchable, which means that each PDF page of the Board Minutes must be read in order to find references. Some of the pages are very faint, and the original books apparently cannot be located by the Board. (We appreciate the efforts of an administrator who tried!)

However, perseverance paid off! On August 11, 1885, the Howard County Board noted that “Hez Brown” was one of the teachers who was confirmed by them “for the Col. Schools.”

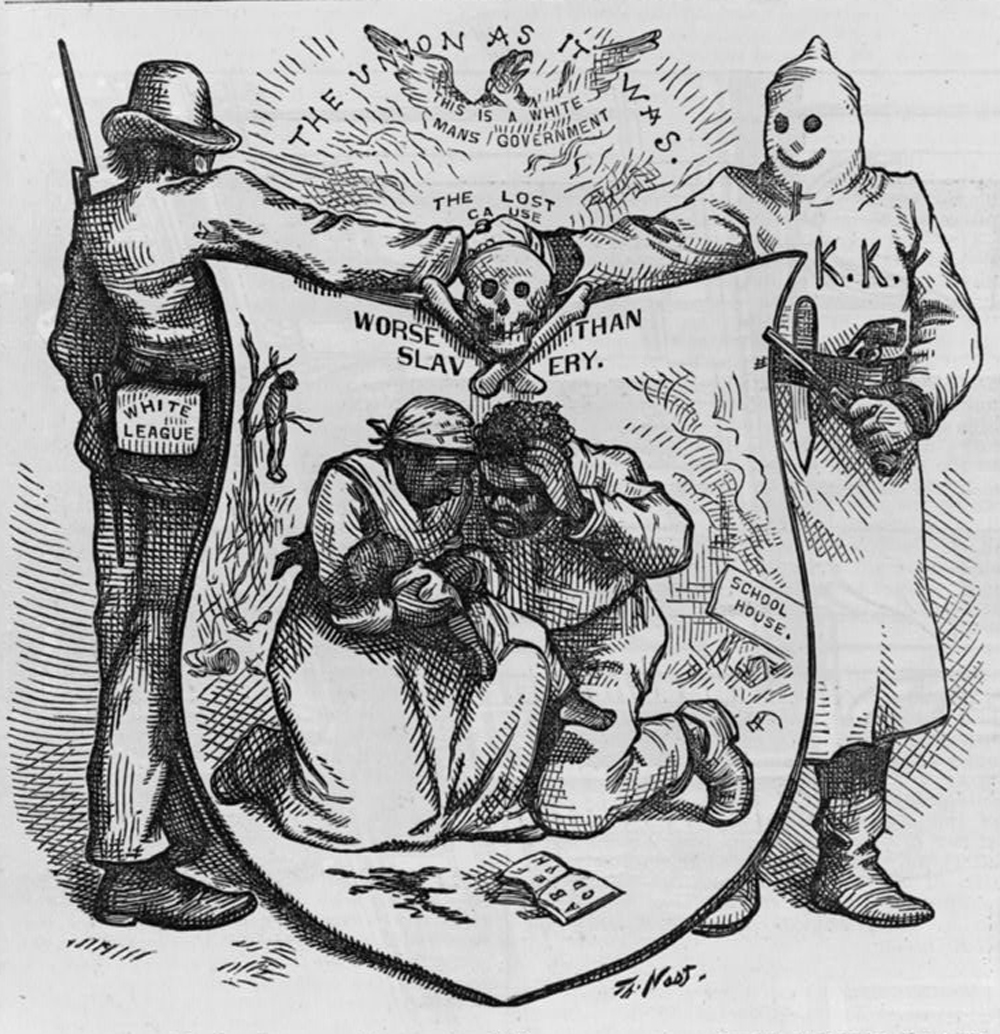

Reference to the KKK?

Although not directly related to Hezekiah Brown, we decided to include in this section another entry in the Board minutes from the year 1886 (on PDF page 4) because it provides important historical context. “K.K.K.” is written into the official record in a way that looks like it may be a doodle or a notation. For at least some Howard Countians at the time, or at least for those who wrote and approved the Board of Education minutes, the Ku Klux Klan was an unobjectionable reference to include in an official record.

Hezekiah Stays in Howard County

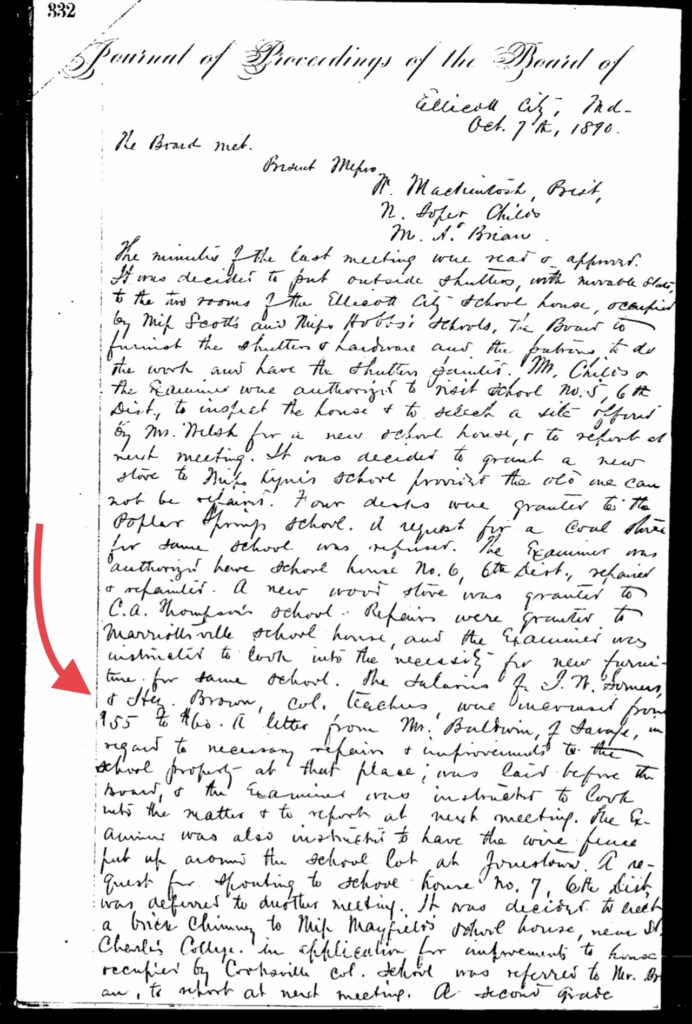

On October 7, 1890, the Board authorized the salary of Hezekiah Brown to be increased from $55 to $60.

On the 1900 census, Hezekiah was listed as being a boarder in the Ellicott City household of Isaac Fuller. He was reported to have a birth year of 1868, and to be 30 years old.

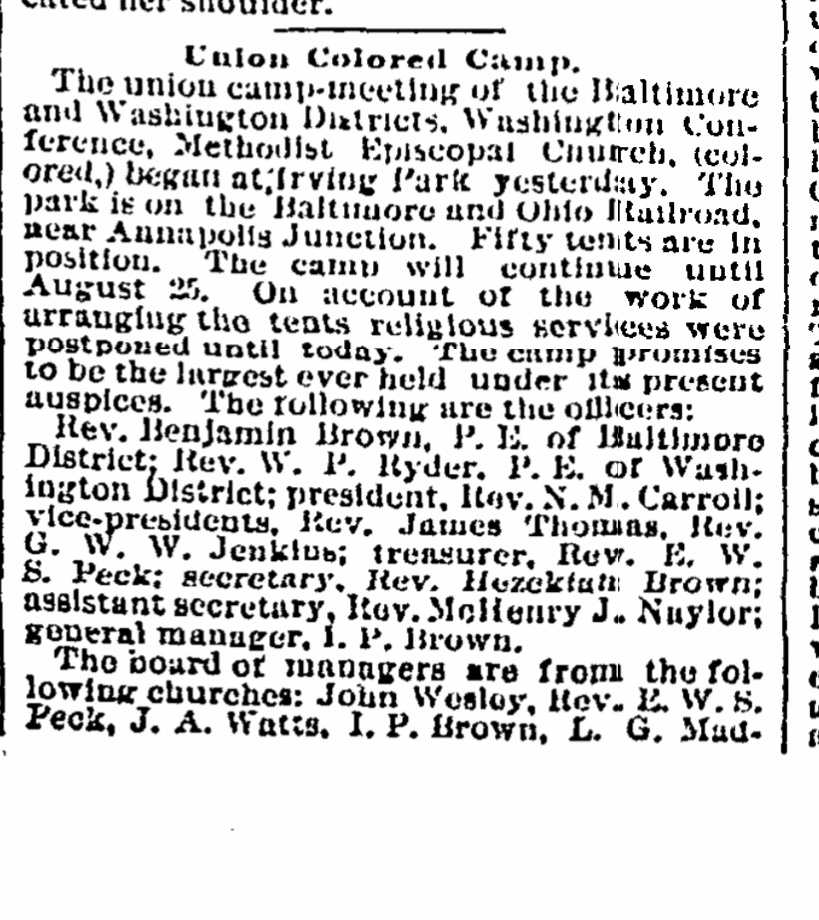

On August 8, 1891, the Baltimore Sun reported that Rev. Hezekiah Brown was an officer (secretary) of a camp meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church. This is the first documentation that substantiated the press reports that he was a reverend. As it was typical for officers at such meetings to be men of the cloth, we have adopted this as his title for this story.

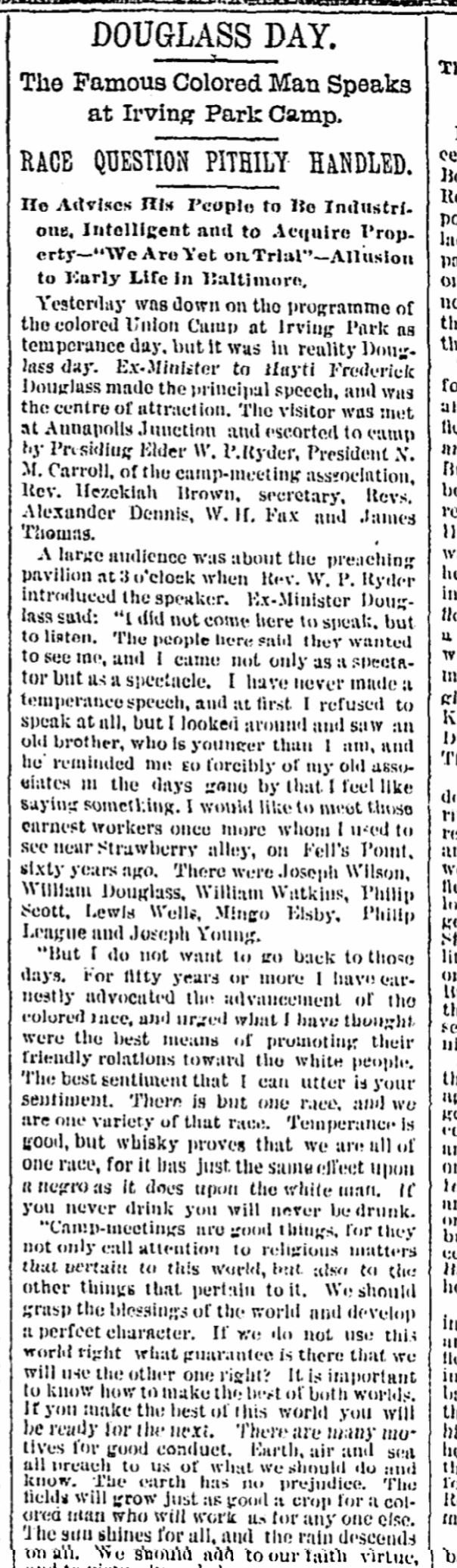

That camp meeting was scheduled to last until August 25th. On August 19th, the area called “Irving Park” in Howard County near Annapolis Junction had a visitor that was known all over the world. This Hezekiah and five other men met Frederick Douglass and escorted him to the Camp meeting!

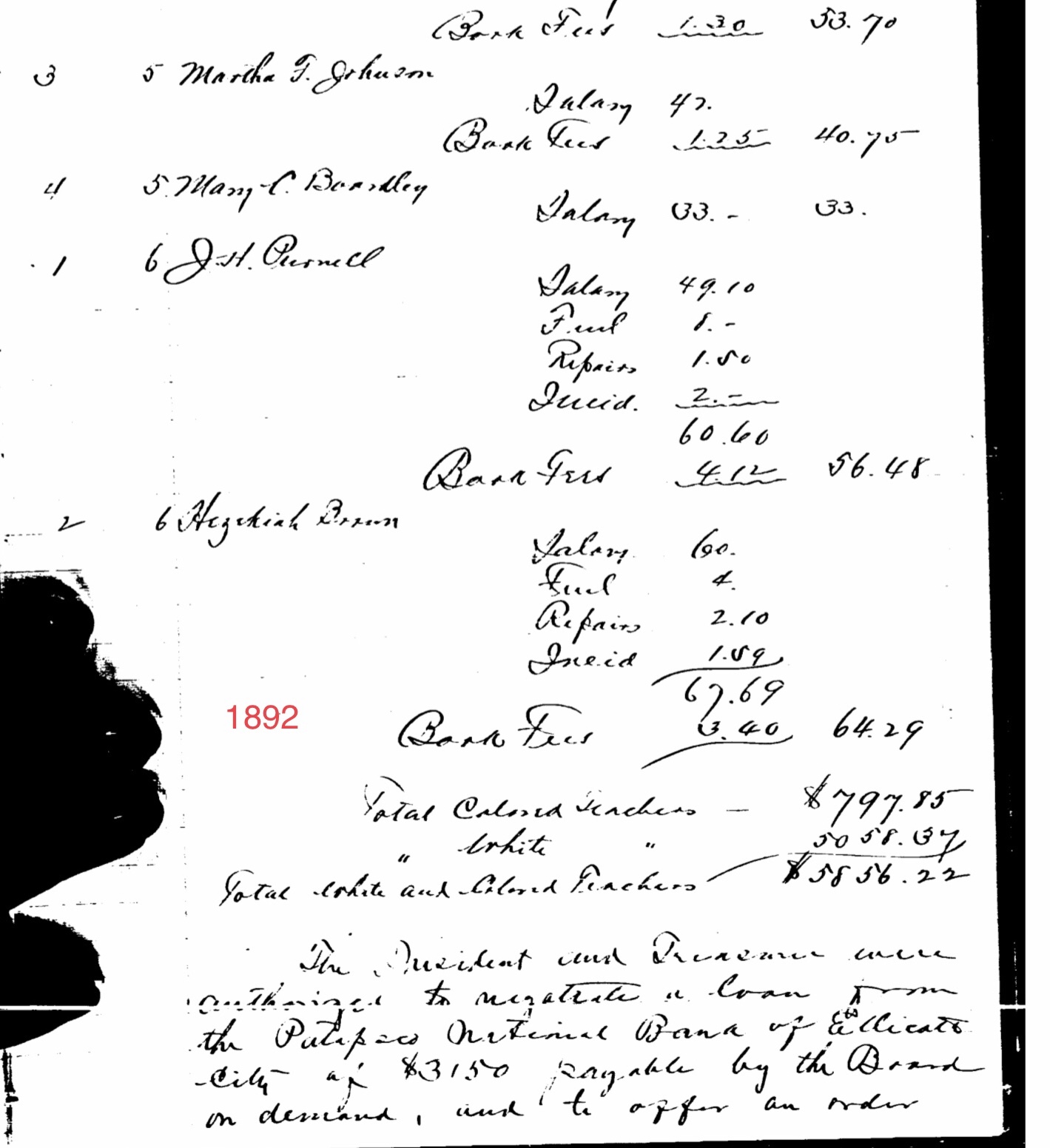

In 1892, Hezekiah’s salary and expenses were noted by the Board as being $67.69.

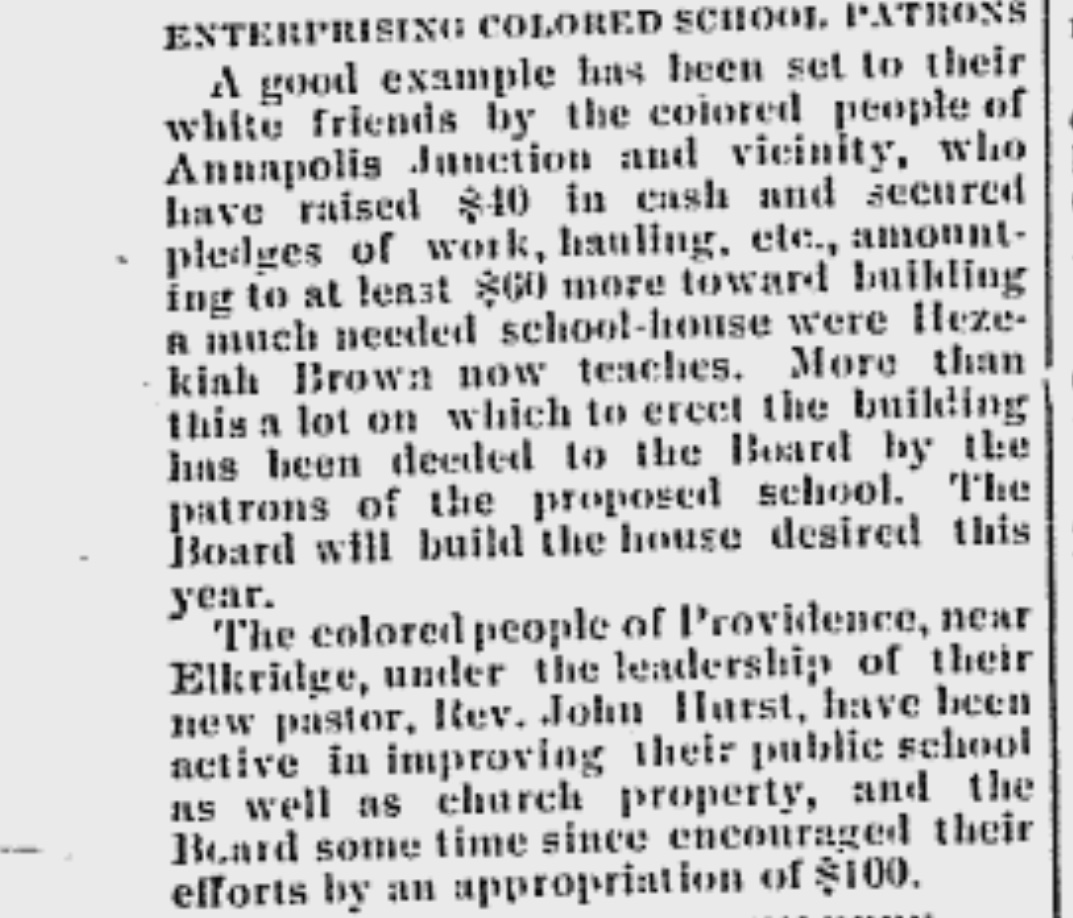

On January 20, 1894, the Ellicott City Times16 reported on the efforts to build a school where this Hezekiah taught. The land was reportedly deeded to the Board by an African American. This was not the first time that the Board received land for the purpose of building a school for African American children.

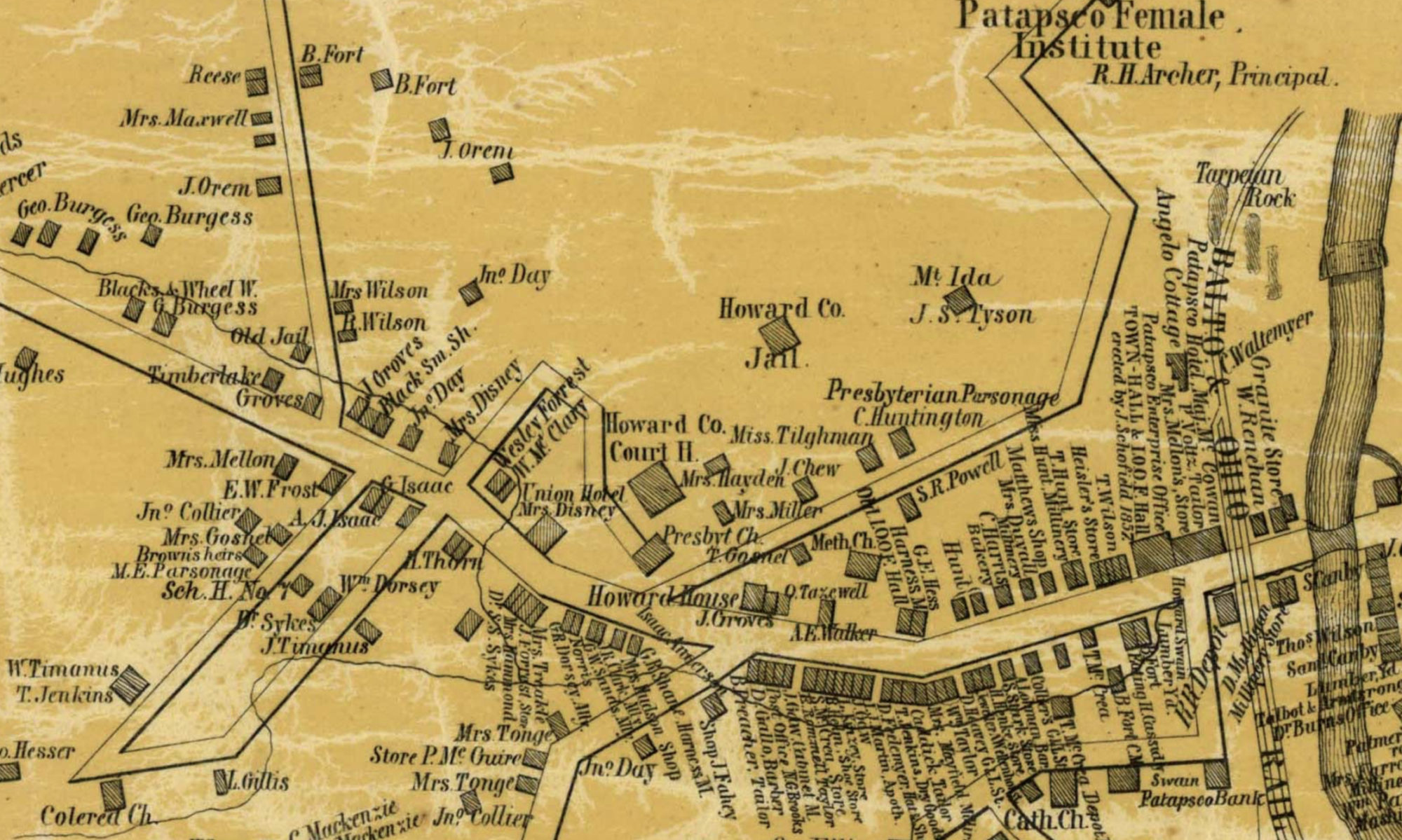

This 1878 map shows the area of Howard County in District 6 where Hezekiah taught and preached and Fannie and her son would have lived. It is also where Hezekiah was reported in such detail to have been lynched. Hezekiah taught at Asbury Chapel (labeled Asbury M.E.Ch. on the map) and reportedly preached there several times. Other versions of this map, including the one at the top of this webpage, add the designation “Col’d” referencing the same church. They are the same place.

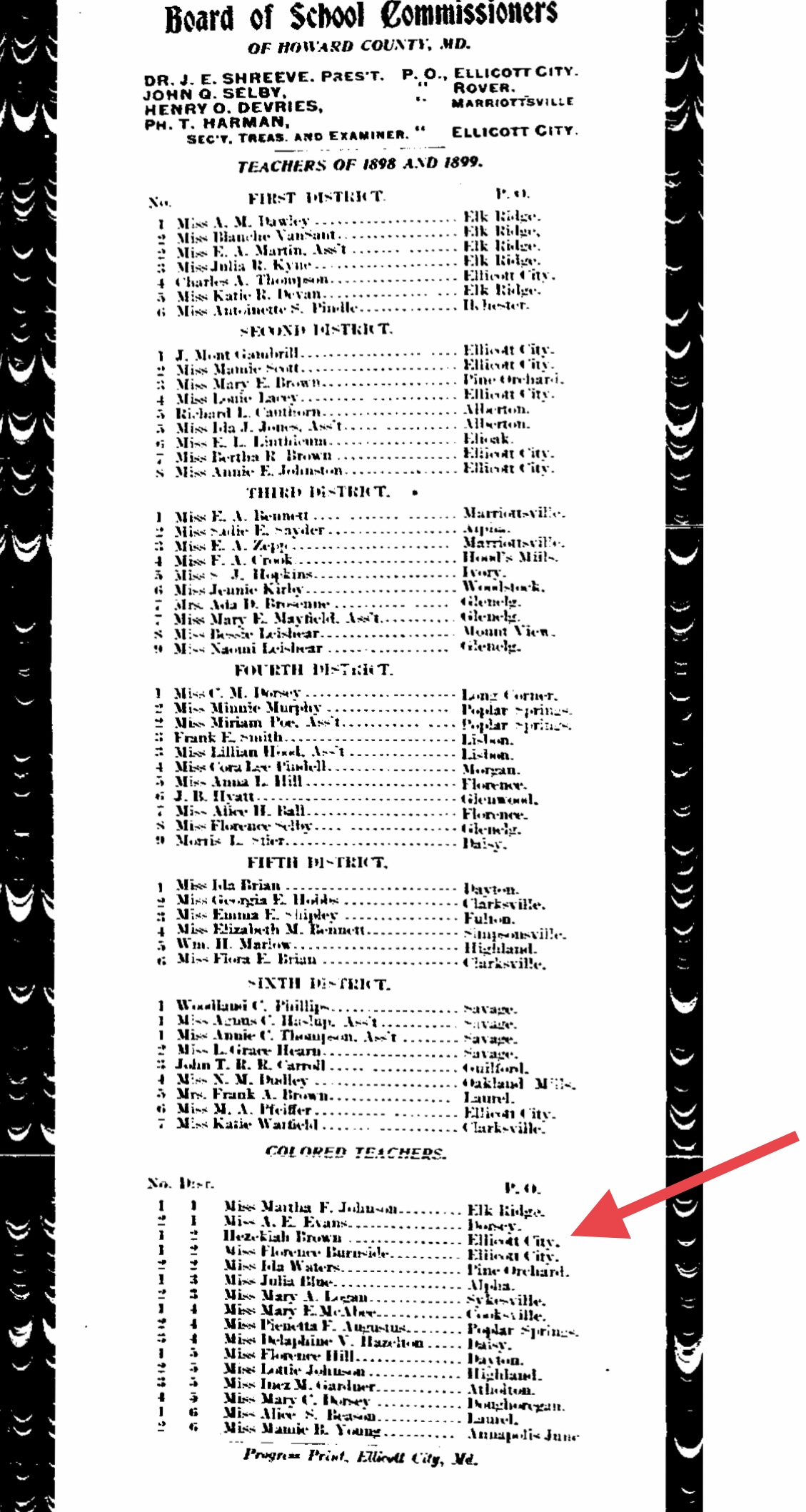

A Board of School Commissioners document records that by the 1898-1899 school year, Hezekiah was teaching at Ellicott City.

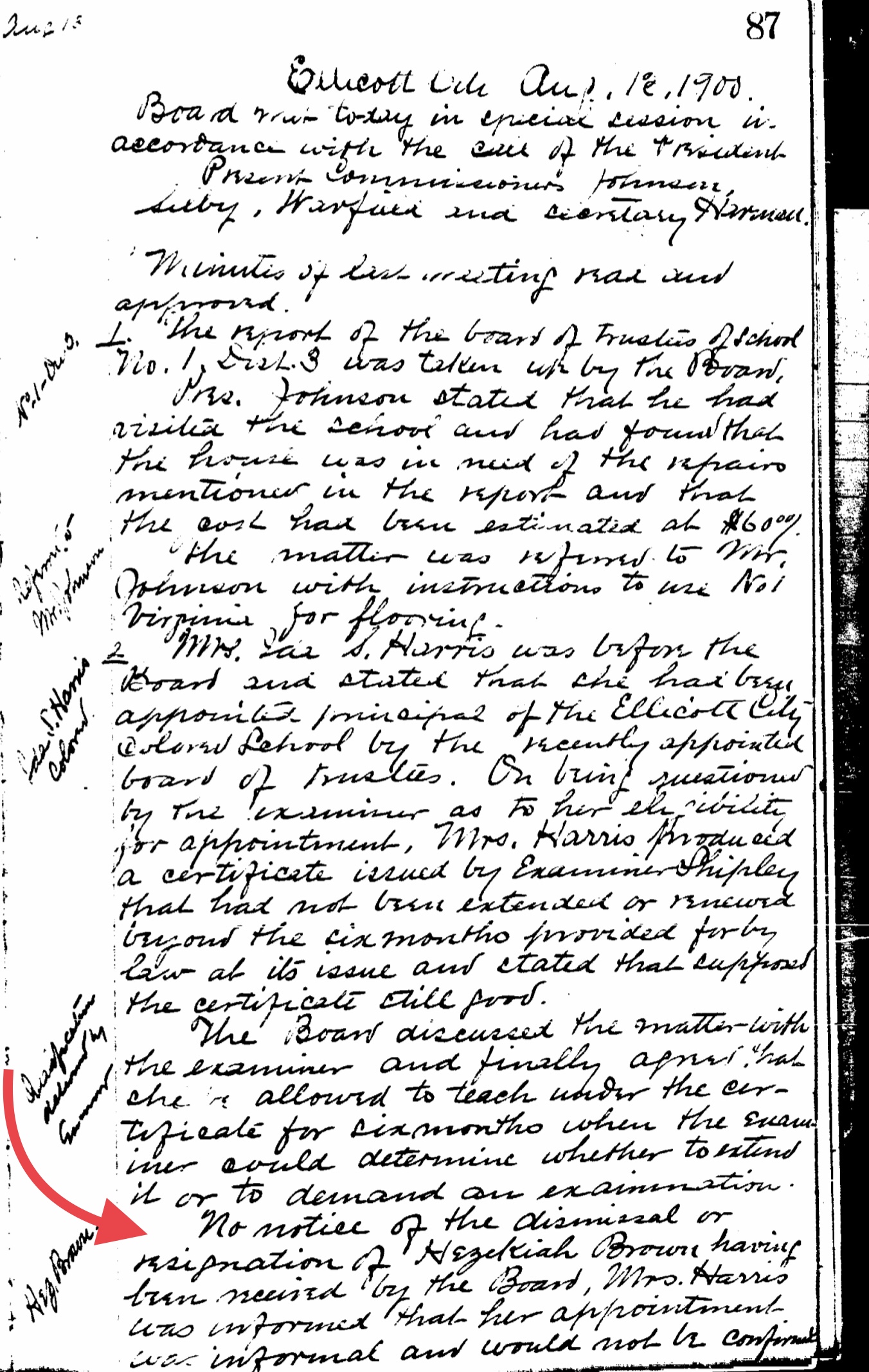

In the August 13, 1900 Board Minutes, Hezekiah Brown, residing in Ellicott City, was noted to be the Principal of the Ellicott City Colored School! We do not know how long he held this position.

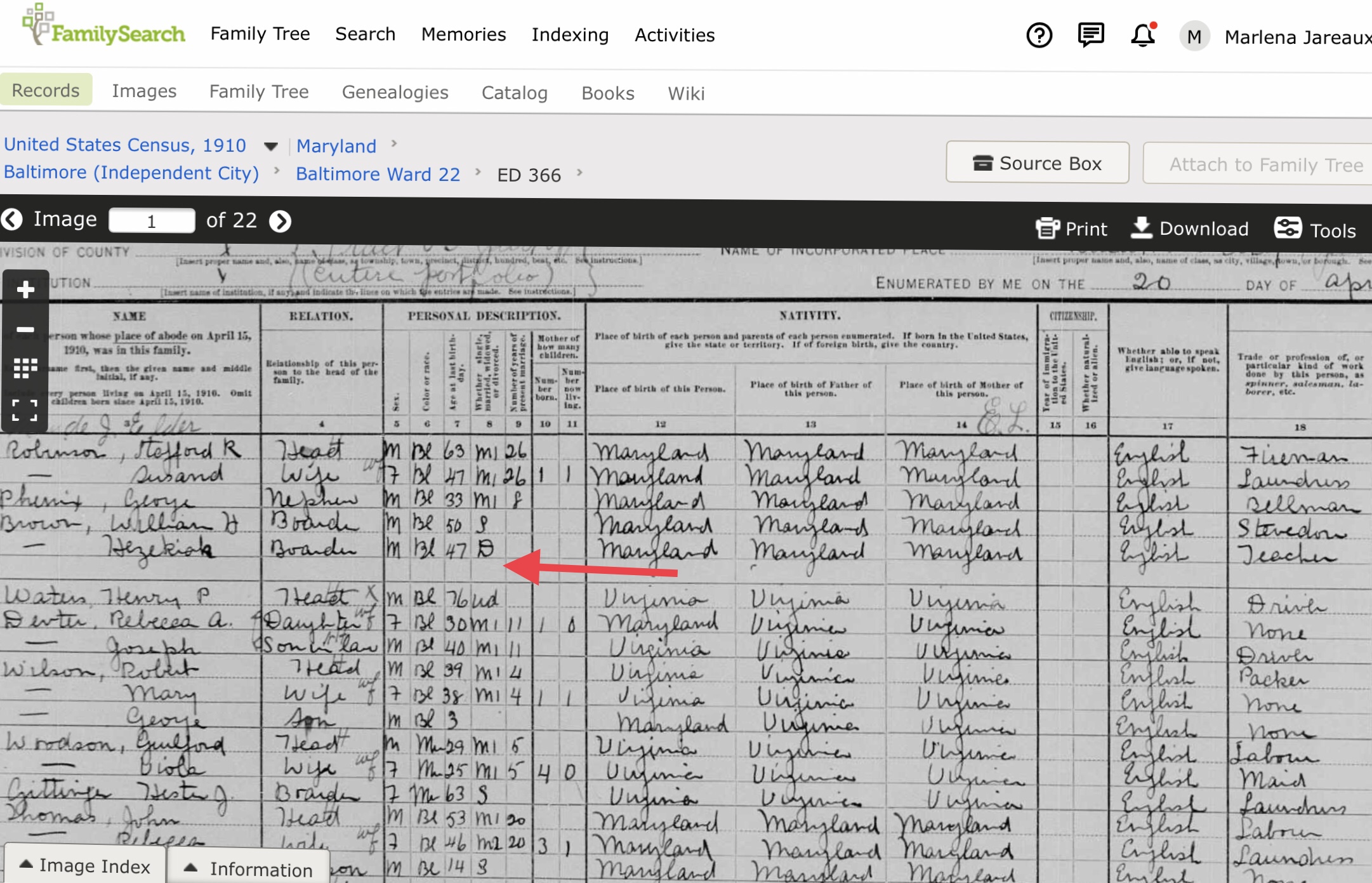

By the 1910 census, Hezekiah, age 47, was listed as living with William H. Brown in Baltimore City. He was noted to be divorced. We have not found any information related to a marriage.

Conclusions:

We have concluded that the Hezekiah Brown born in the early 1860s, who was living in Baltimore in 1880, was the Hezekiah who was falsely reported to have been lynched in December 1884. Regardless, the information unearthed in the search sheds important light on the intentional and systemic barriers that were constructed to ensure that African Americans did not have access to an equal education in Howard County and across the state of Maryland. Importantly, we also learned of the tenacious efforts of African Americans to overcome these barriers. A great deal of information regarding the desire for equal education and the challenges to obtaining it both in Maryland and Howard County has been compiled, with only a fraction of it being included herein due to space considerations.

BOTH of these men impacted the lives of countless people. The younger Hezekiah was born free as the Civil War was raging on but came to Howard County to teach in a time when it was a struggle for African American children to receive equal educational opportunities, while the older Hezekiah was born free during the time when slavery was more deeply entrenched in the country. Hezekiah M. Brown was obviously determined to partake in rights of citizenship made available to him by virtue of his opportunity to get a college education, along with opportunities made possible in Georgia in part due to the federal occupation of troops during Reconstruction. He was able to work as a teacher while the younger Hezekiah was just a boy, and he bought his first lot of land shortly thereafter in 1869. Both of these men impacted the lives of many children in times when that job was dangerous.

Role of the Press

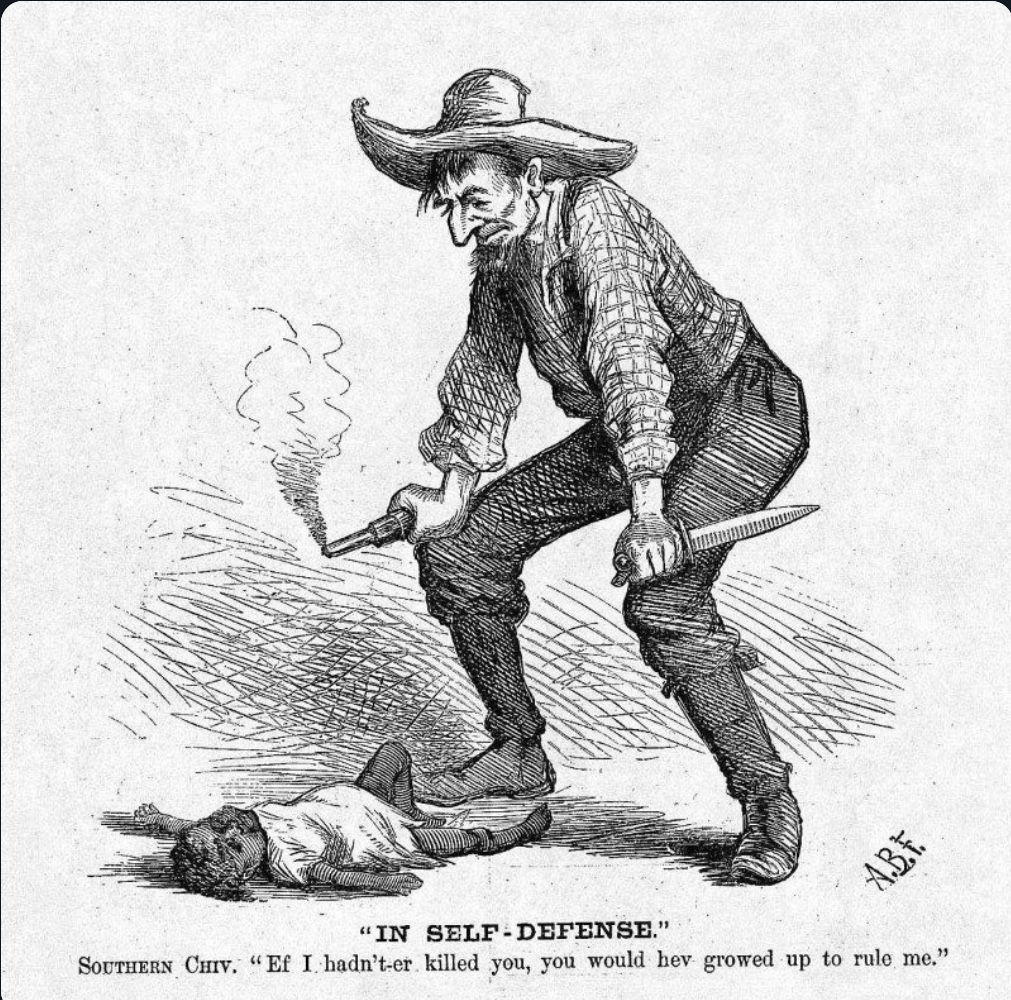

It is important to remember that both men lived during a time when the press enforced the racial hierarchy with the following types of images. (Note the image of a man being lynched and schools burning in the second image, with white supremacy groups depicted.)

The Fate Of The Georgia Hezekiah M. Brown:

It is likely that the Georgia-based Hezekiah lost another child named Hezekiah. On June 11, 1885, baby Hezekiah passed away at age 2 months and 22 days. In March of 1897, Hezekiah petitioned the courts to be the administrator for his wife’s estate after her death.17 She was 13 years younger than him, and her cause of death is not known. By 1900, he was listed on the Chatham census living with his 6-year-old son, George. Hezekiah M. Brown passed away on July 3, 1918 and was buried in Laurel Grove cemetery with his children.

The Fate of the Baltimore Hezekiah

We lost the trail of this Hezekiah after 1910. Perhaps our writeup will inspire someone to trace his story to determine what eventually happened to him. Next time you drive down Main Street in Ellicott City and pass the restored Ellicott City Colored School, think of Hezekiah teaching and later becoming the principal there!

Hezekiah would have had a unique perspective on the lynching of Nicholas Snowden in 1885. He also may have known Jacob Henson, Jr., who in 1895 worked on Main Street near the Ellicott City Colored School. There are no documented lynchings of African American men in Baltimore City. Perhaps Hezekiah decided that it was a safer place to live and moved back there.

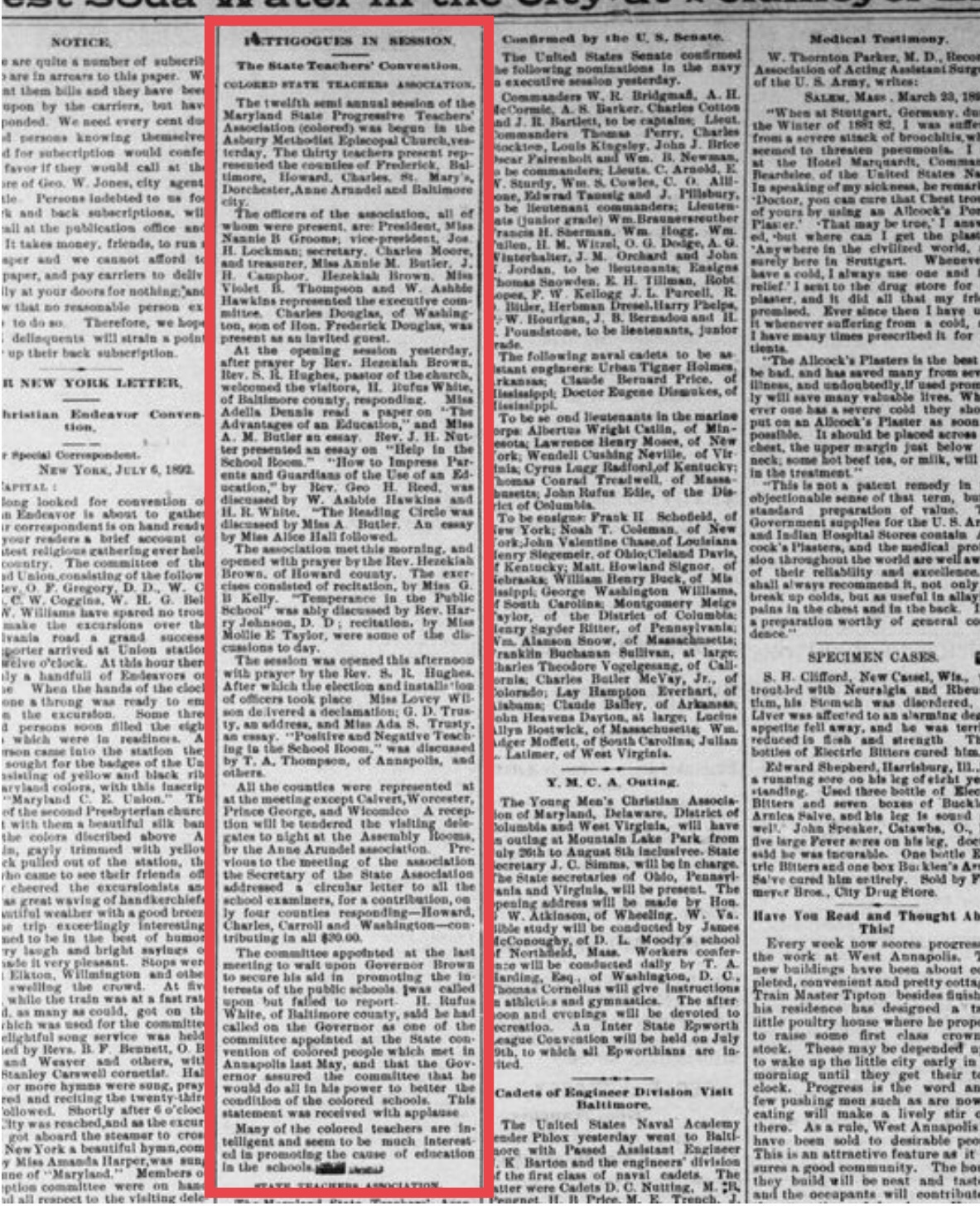

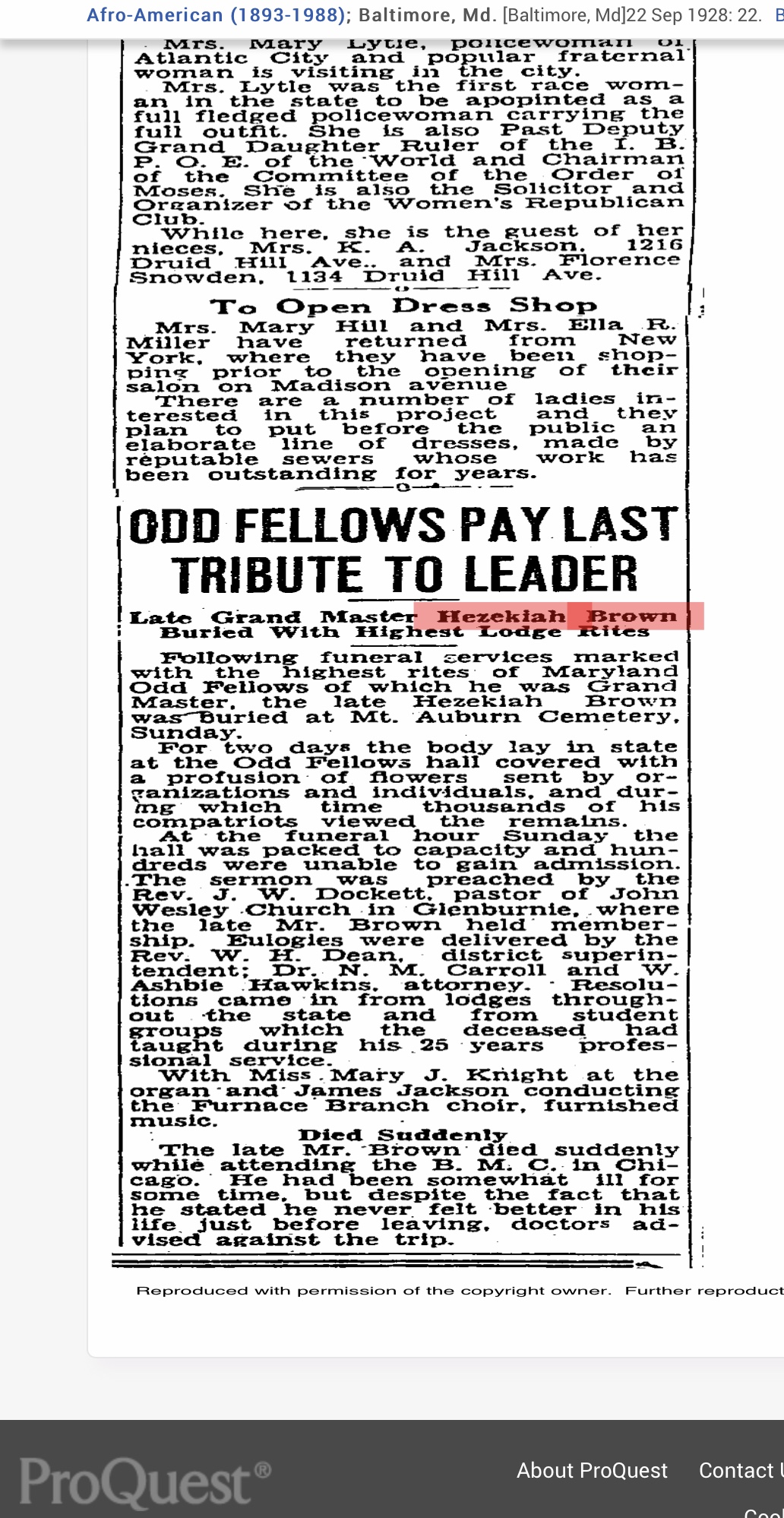

As an interesting aside, we came across an article in 1892 that references Rev. Hezekiah Brown having an acquaintance with W. Ashbie Hawkins, who was the legal counsel for Jacob Henson, Jr. More to come on this in the story of Mr. Henson’s life…

A zoomed-in view of the relevant part:

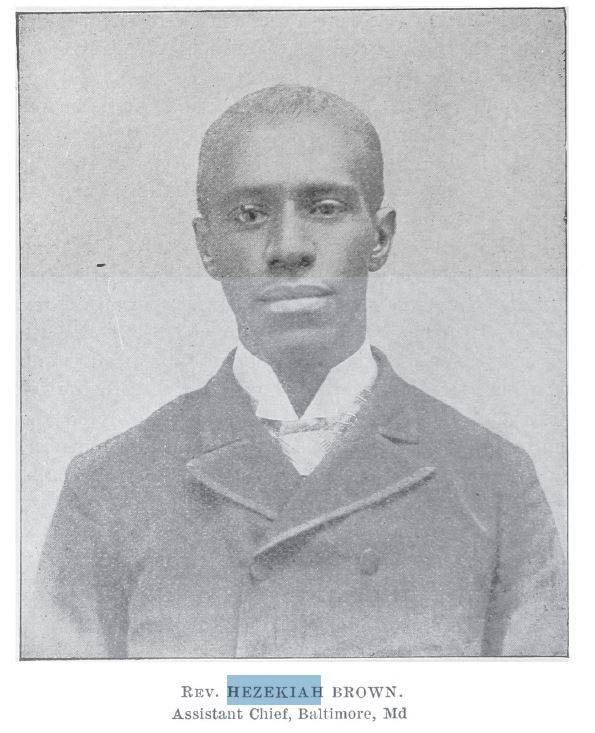

UPDATE A face can be put to the name for Reverend Hezekiah Brown, thanks to the great work of a researcher (Wayne Davis) interested in our group’s work. Introducing… the Reverend Hezekiah Brown:

Additional updates are:

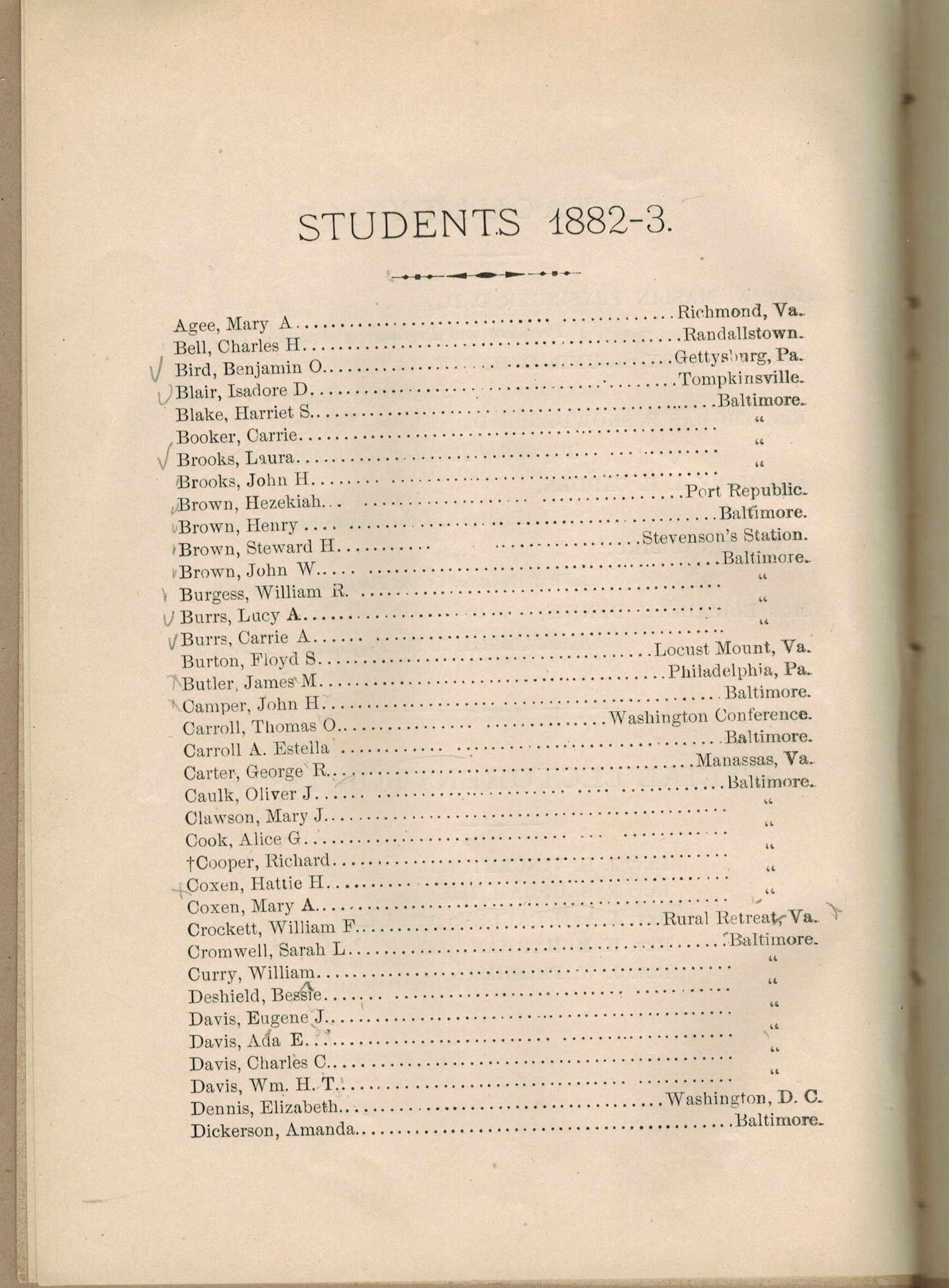

He was a college-educated man also. He attended Centenary Biblical Institute (later becoming Morgan College in 1890). He was listed as a student in the 1879-81, 1881-82 and 1882-83 catalogs. This is from his final year of matriculation:

In addition, Hezekiah was found to have been reported on during the occasion of his death in 1928.

No article has been located in The Sun regarding Hezekiah’s death or funeral service.

The Afro-American reported on the thousands of people who payed their final respects over 2 days while his body laid in state in Baltimore.

Questions for the Reader

1. What might we conclude about the culture in Howard County and prevailing attitudes of its white residents that the false narrative of a lynching that did not happen was reported in such detail? For example, the December 13, 1884 article references “13 masked men” and that he was hung “over the bough of a chestnut tree.”

2. What was the role of the press in perpetuating a culture of white supremacy, and what accountability does it bear?

3. One of the articles was printed on December 25, 1884 – nearly two weeks after the falsely reported lynching event. What was Hezekiah experiencing during this protracted period of time?

4. What would have been the impact of the falsely reported lynching on the African American community of Howard County?

5. Discussions about racial disparities across a range of educational outcomes continue to this day in the Howard County Public School System. How does the information in The Tale of Two Hezekiahs contribute to the ongoing dialogue about these disparities?

Additional Resources:

John B. Bailey’s fascinating story can be found here:

https://thenegroinsports.blogspot.com/2014/02/born-free-in1815-in-baltimore-maryland.html

Information about Laurel Grove cemetery, where the Georgia Hezekiah is buried:

https://gallivantertours.com/savannah/historic-cemeteries/laurel-grove-cemetery/

Burial info for many of the Georgia based Brown family:

http://www.interment.net/data/us/ga/chatham/laurel-grove-south-cemetery-records-br.htm

More information about Free Town, Howard County:

More on Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church:

https://data.howardcountymd.gov/scannedpdf/Historic_Sites/HO-337.pdf

It’s exciting to think that Hezekiah may also have also participated in activities at this lodge built next to the Asbury church. Mt Moriah Lodge 7:

https://mht.maryland.gov/secure/medusa/PDF/Howard/HO-800.pdf

For more info on the educational system that the Georgia based Rev Hezekiah M. Brown would have been a part of in Georgia, you can read more here to learn what he would have faced:

- http://www.chestercohistorical.org/sites/default/files/411%2C131D%20Brinton%20guide2008.pdf [↩]

- https://civilwarhome.com/shermanandministers.htm#:~:text=Sherman%20Meets%20The%20Colored%20Ministers%20In%20Savannah.%20Minutes,M.%20Stanton%2C%20Secretary%20of%20War%2C%20an d%20Major%20 [↩]

- https://warwashere.com/tag/montmollin-building/ [↩]

- https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbaapc.34600/?sp=19 [↩]

- https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000190/pdf/am190–3229.pdf [↩]

- https://www.archives.gov/files/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau/maryland-and-delaware.pdf [↩]

- https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000190/html/am190–3208.html [↩]

- http://aomol.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000190/html/am190–2811.html [↩]

- https://go.boarddocs.com/mabe/hcpssmd/Board.nsf/files/85TLDT5619BF/$file/09+05+1865+to+12+23+1885.pdf [↩]

- “United States, Freedmen’s Bureau, Records of the Superintendent of Education and of the Division of Education, 1865-1872,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9TH-KSTZ-K?cc=2427894&wc=313M-DP8%3A1556056502%2C1556113411 : 9 March 2015), District of Columbia > Roll 1, Fair copies of letters sent, vol 1-2, 1868-1870 > image 43 of 529; citing multiple NARA microfilm publications (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1969-1978) [↩]

- https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013700/013731/images/sun28nov1884.pdf [↩]

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=9fSugHr6AN8C&dat=18841212&printsec=frontpage&hl=en [↩]

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=mh5EAAAAIBAJ&sjid=8rAMAAAAIBAJ&pg=5780%2C6643054 [↩]

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=mx5EAAAAIBAJ&sjid=8rAMAAAAIBAJ&pg=7230%2C6685944 [↩]

- https://blog.newspapers.com/destruction-of-the-1890-census/ [↩]

- msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc4800/sc4872/007987/html/m7987-0014.html [↩]

- https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063034/1897-03-24/ed-1/seq-3/ [↩]