Each Christmas for more than 20 years now, I have been fortunate to celebrate it as a mother. Once my son graduated from Hammond High, he spent time away while at the University of Maryland but returned home for the holidays to celebrate. A recent “Facebook memory” appeared in my account that contained the photo of him when he was about 10 with his HC Parks & Rec trophy for tennis, and my immediate thought was that even now, I still see “my baby” in him. I’m sure I’m not in the minority when I write that there’s very little I won’t do for my son. This Christmas was a little different for me, in more ways than just COVID-19 related. Due to the work our group is doing, I ran across a story that weighed on my mind this Christmas. It’s a story from many Christmases ago in Howard County, and it involves a woman and mother named Caroline.

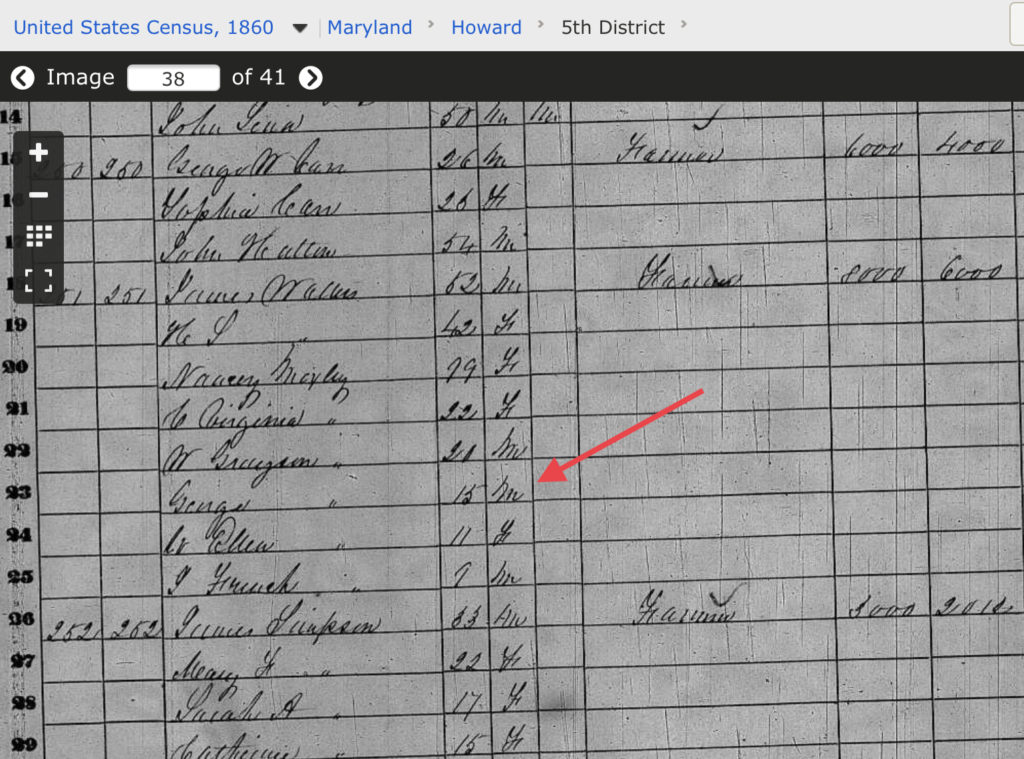

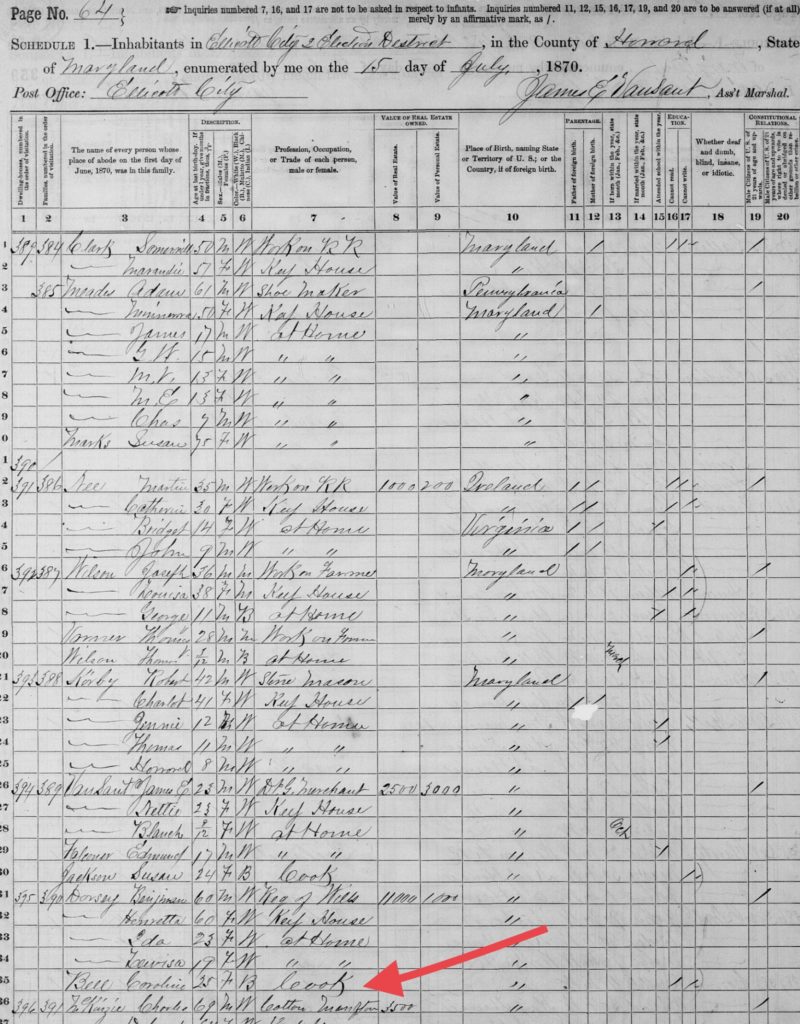

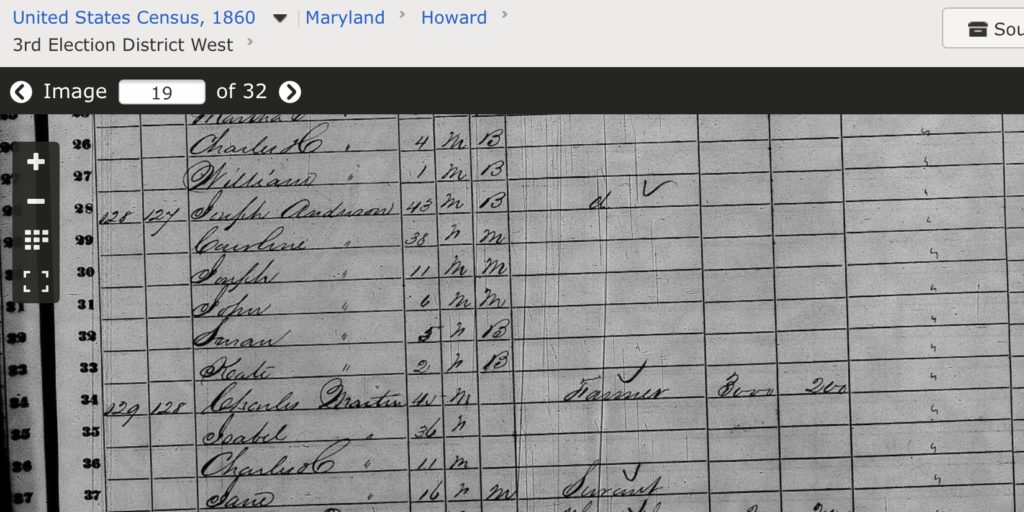

Caroline and her husband Joseph were living in district 3 of Howard County in 1860. She was 38 years old, and had 4 kids living at home with her and her husband. Joseph, John, Susan, and Kate were their names. Joseph was the oldest at 11, and Kate was the youngest at 2. They were a free Black family.

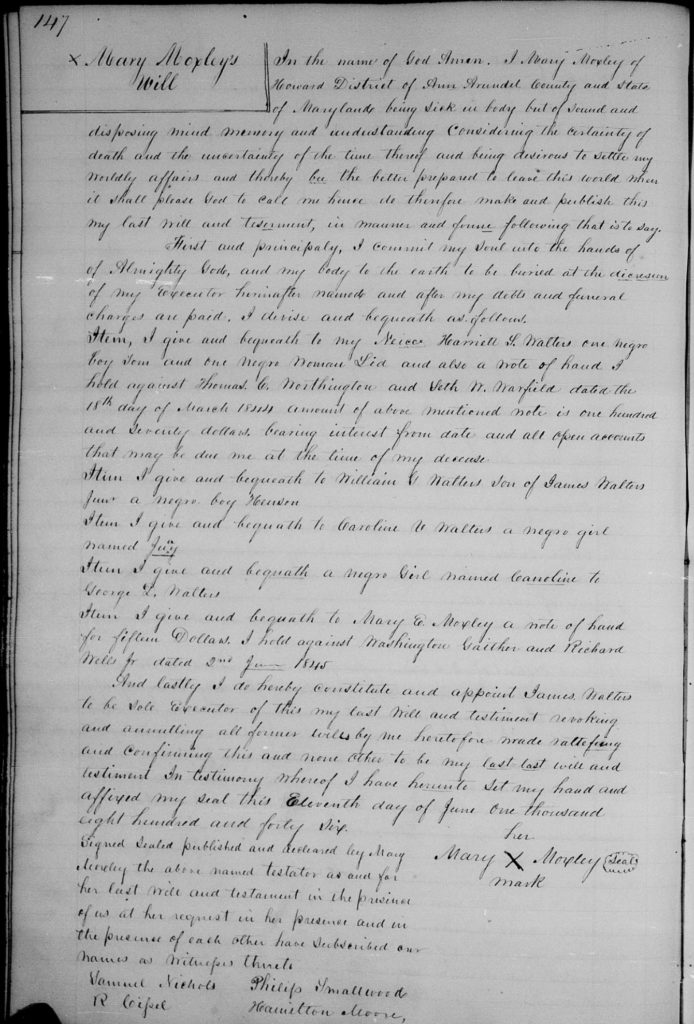

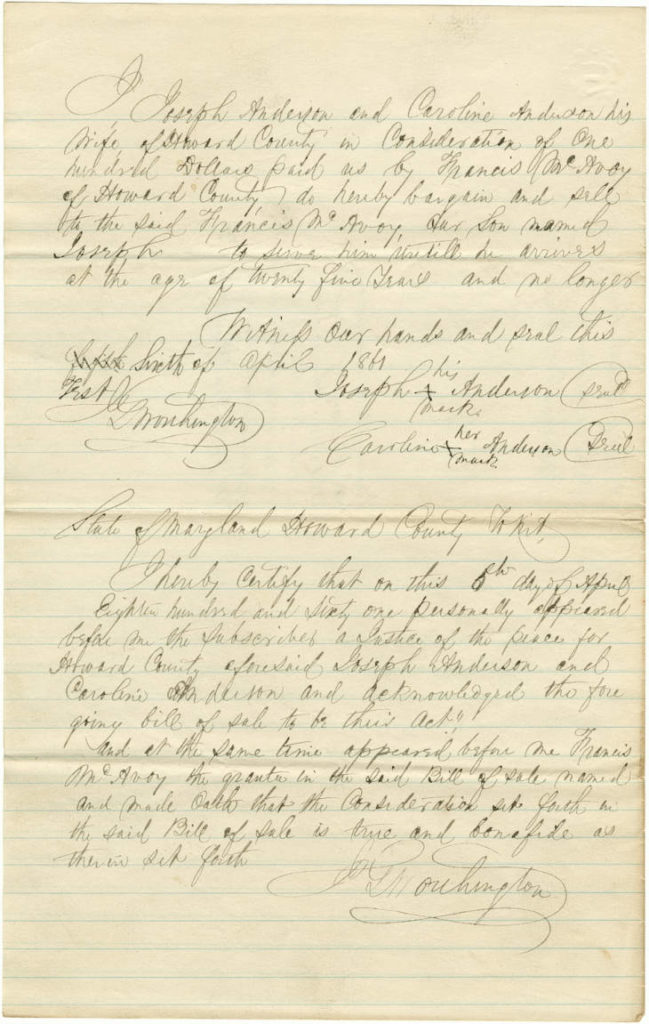

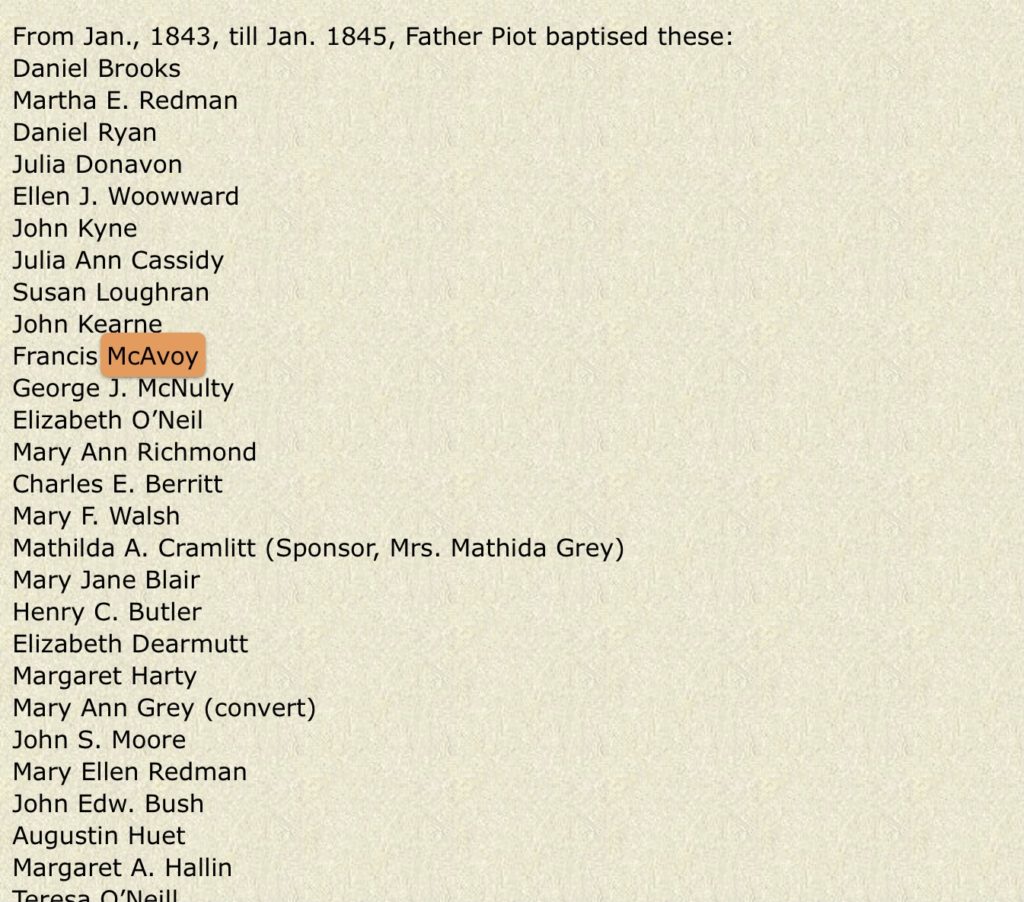

Maryland apprenticeship laws from 1819 were still in place that permitted the children of free negroes to be bound out as apprentices by the local Orphan’s Court if anyone reported their suspicion that they believed a negro child was “not at service or learning a trade, or employed in the service of their parents”. If bound out as an apprentice that way, the master or mistress could be required to teach the child to read or write, or give the child money at the end of their indenture period for what was called “freedom dues”. On April 6,1861, Joseph and Caroline struck their own deal with Francis McAvoy for the service of their son Joseph for $100 paid up front to them. They agreed that Joseph would work for Mr. McAvoy until he turned 25.

This was before the start of the Civil War (April 12, 1861), but after Abraham Lincoln had been inaugurated President (March 4, 1861). Howard County voters weren’t keen on Lincoln or his ideals, having cast only ONE vote for him in the election.

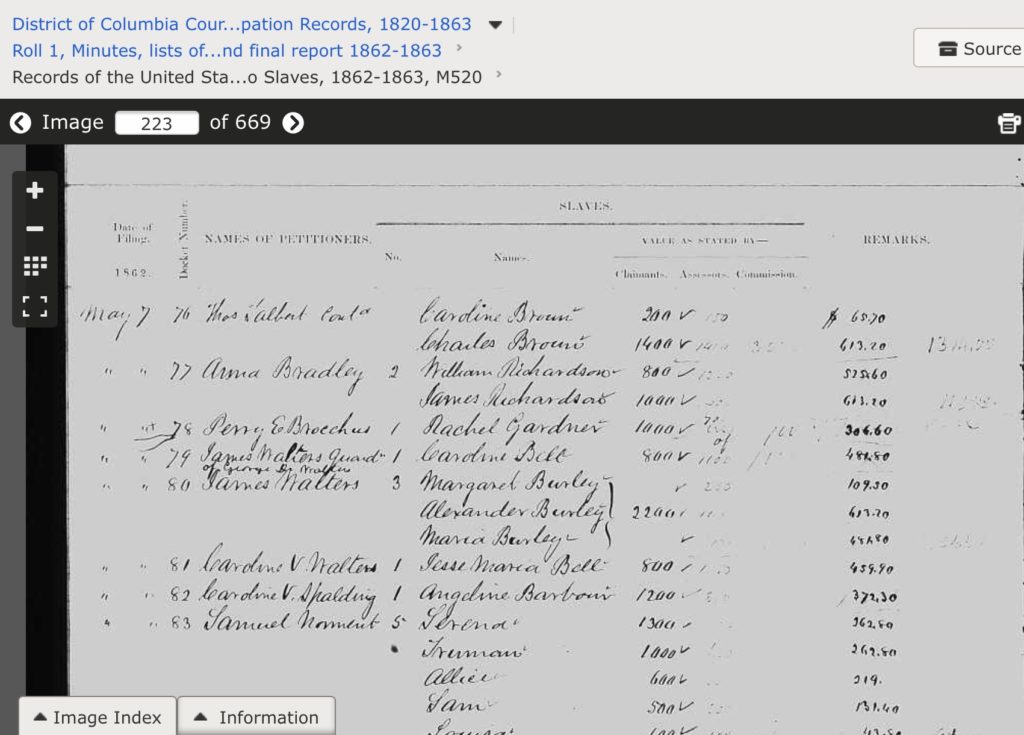

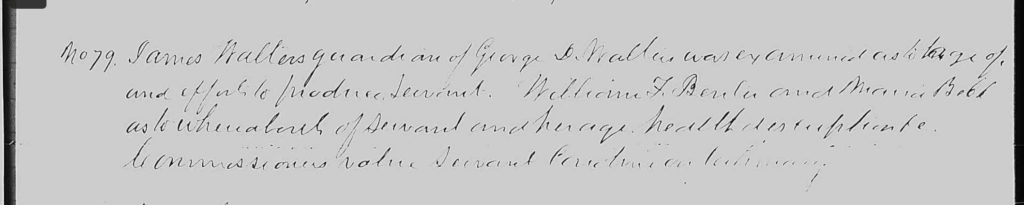

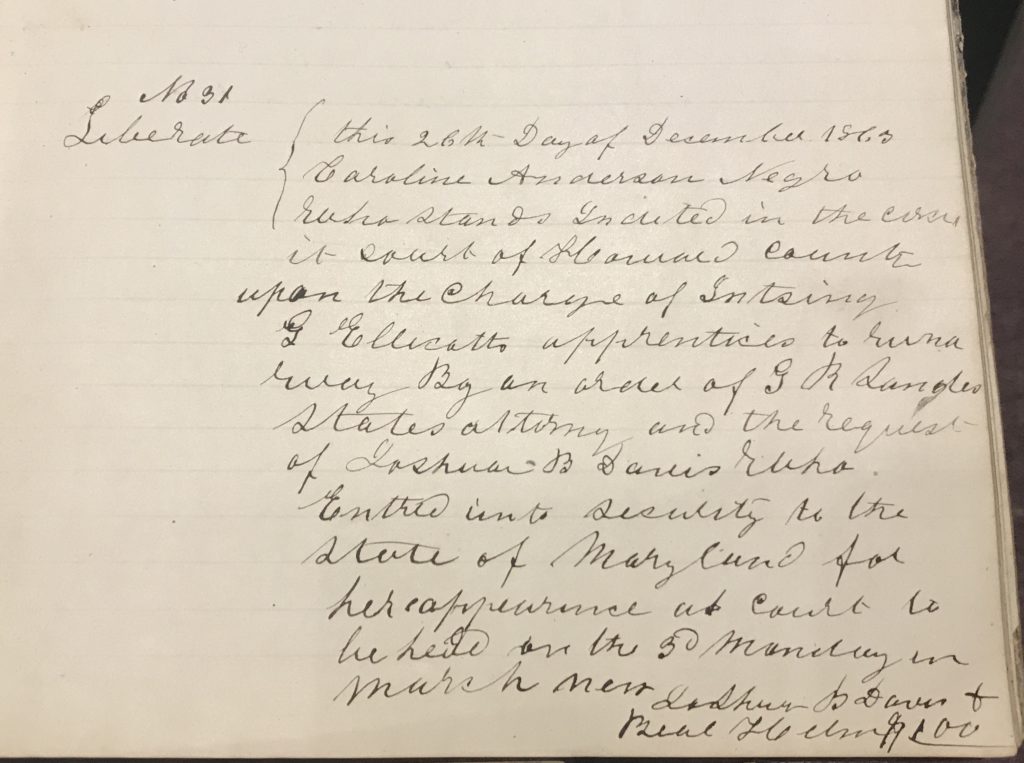

I will never know for certain all that Caroline Anderson personally did in response to the Civil War, states seceding from the Union, and the Compensated Emancipation Act that took effect in neighboring DC in 1862 (but not in Maryland). What I do know is that she was sitting in jail Christmas 1863, having been indicted on charges of enticing the apprentices of George Ellicott to run away from him. ELLICOTT… a name that is usually globally associated with the Quaker faith and antislavery. George had been noted to be an enslaver in 1850.

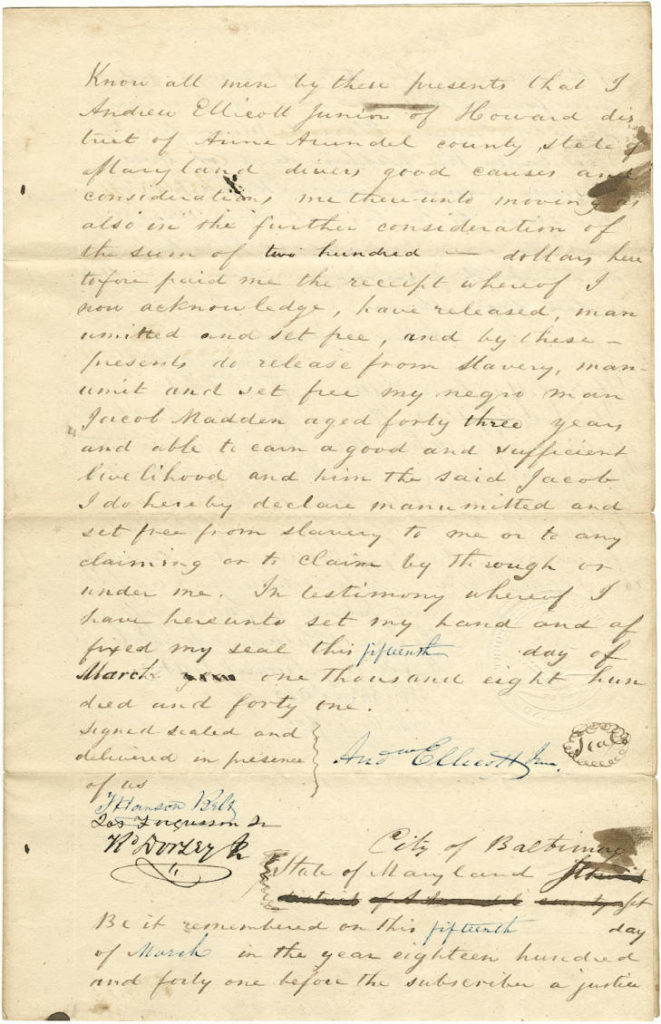

He wasn’t the only Ellicott who was an enslaver, since Andrew Ellicott, Jr also indulged in enslavement. Here, he set 43 year old Jacob Madden free, for the price of $200.

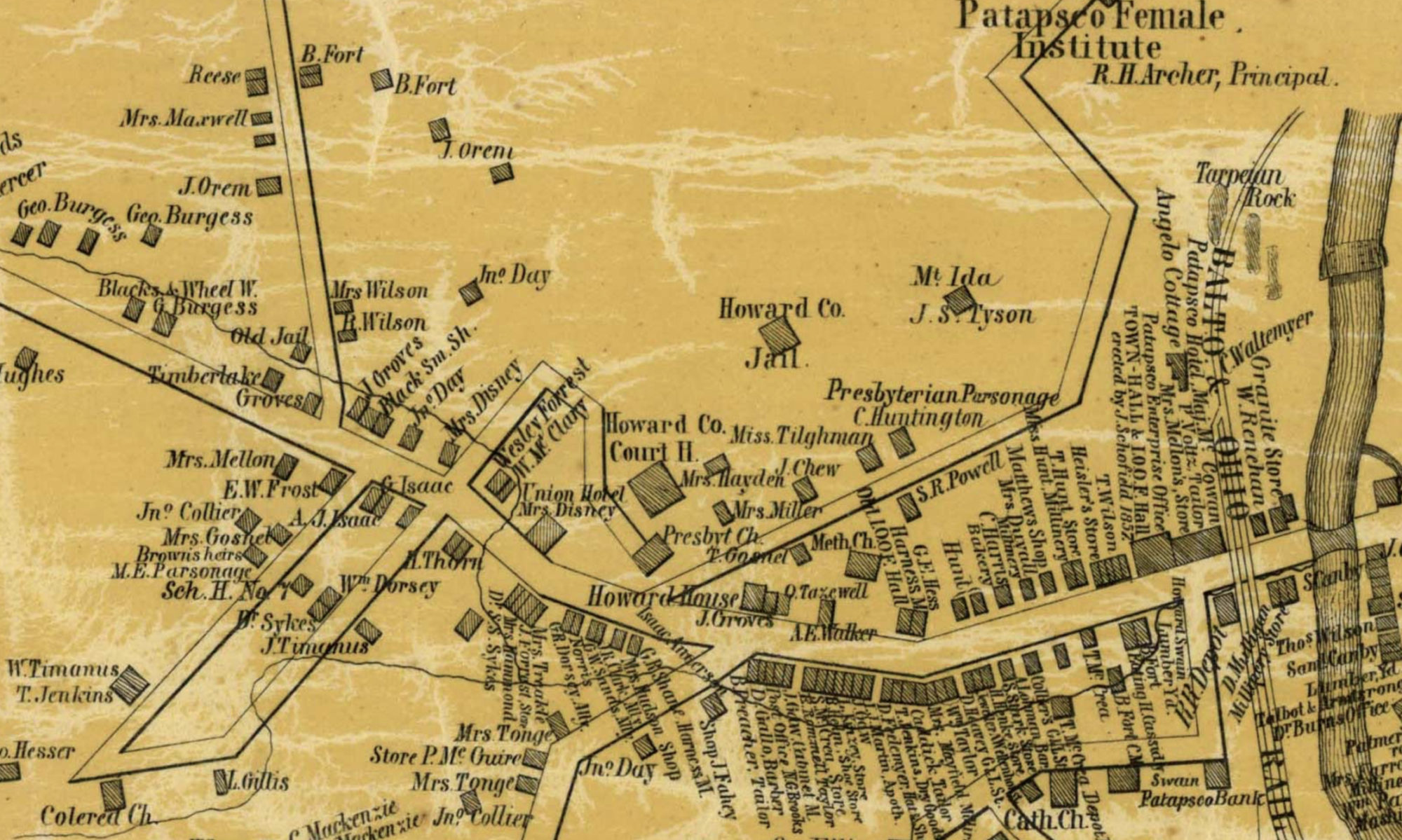

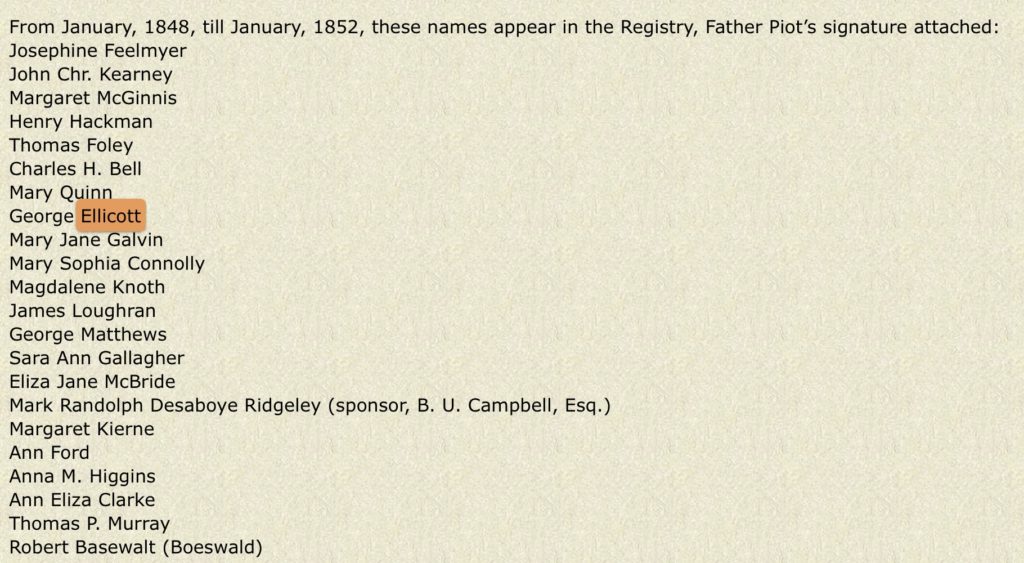

In the years to come, I hope that the work that our group does helps to tear down global assumptions made about people that society of the past has uplifted as well as those that haven’t enjoyed the privilege of being exalted. Society can benefit by having more people who take time to consider and realize the individual stories and circumstances of people (past, present and in the future) before judging them. George very likely knew Francis McAvoy, because it appears that they both attended St. Paul Catholic Church in Ellicott City. McAvoy was baptized there, and a George Ellicott appeared on the registry (likely the father, George II, since his son was only an infant child’s that time).

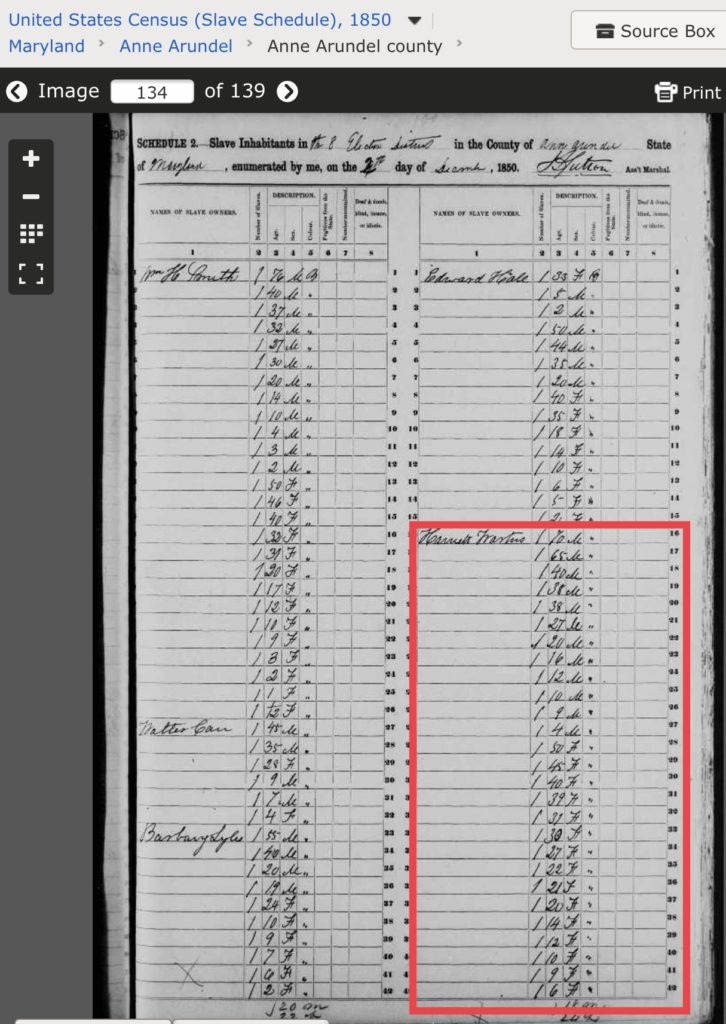

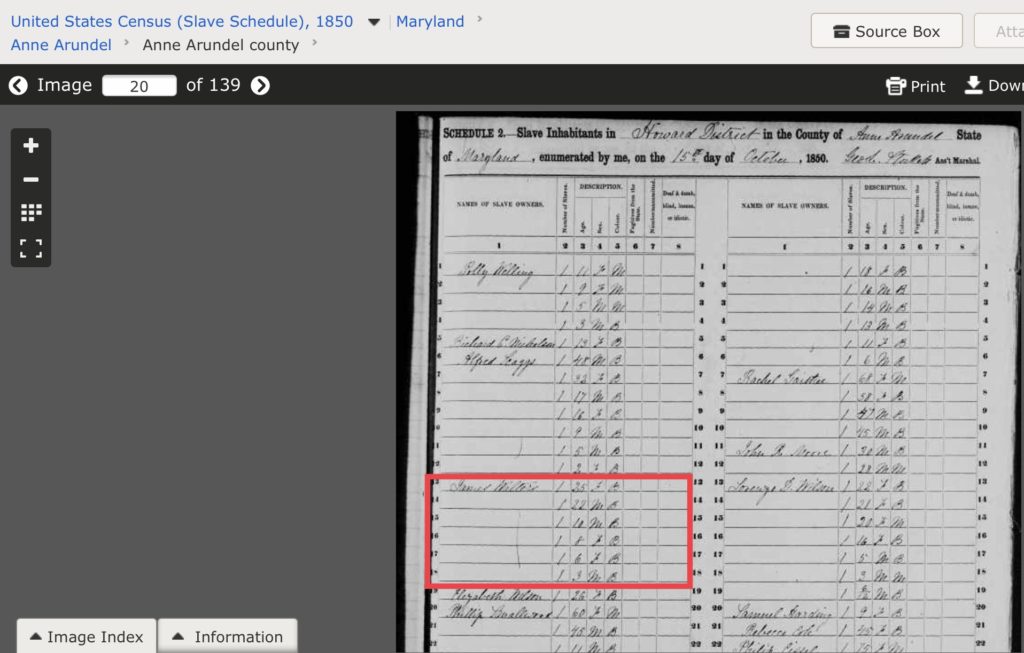

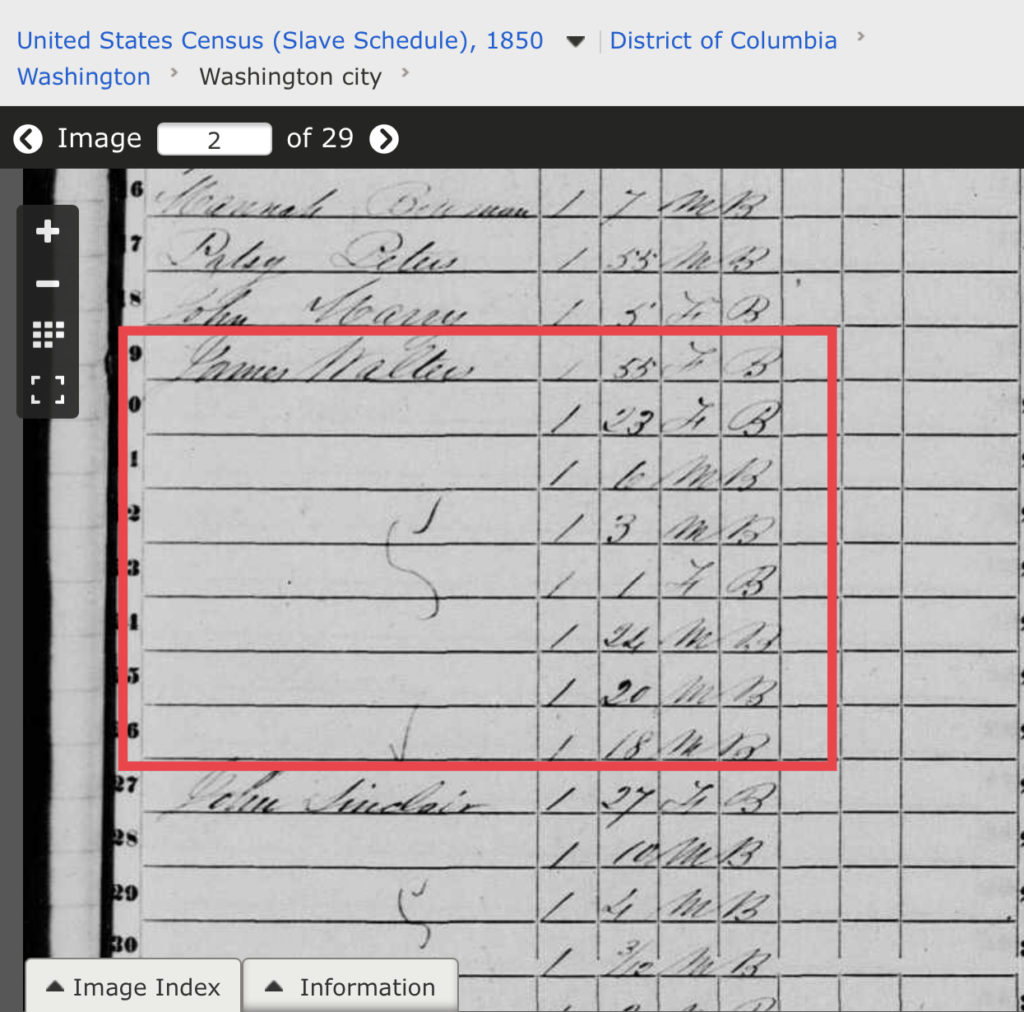

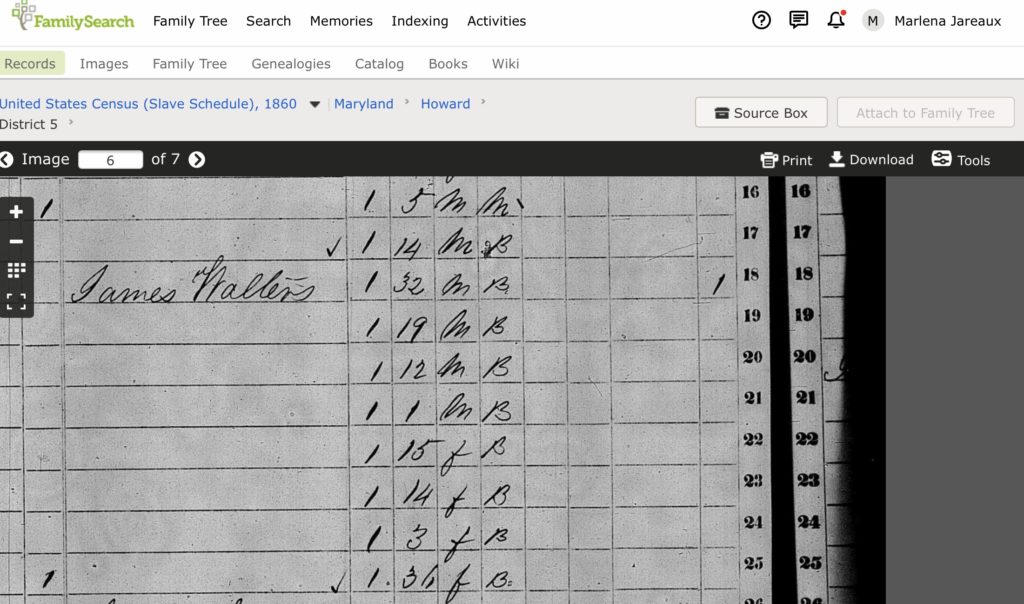

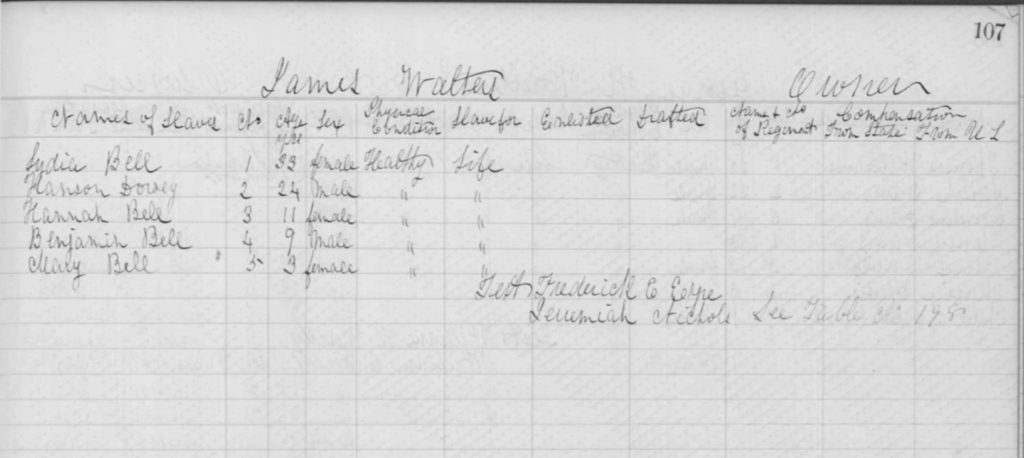

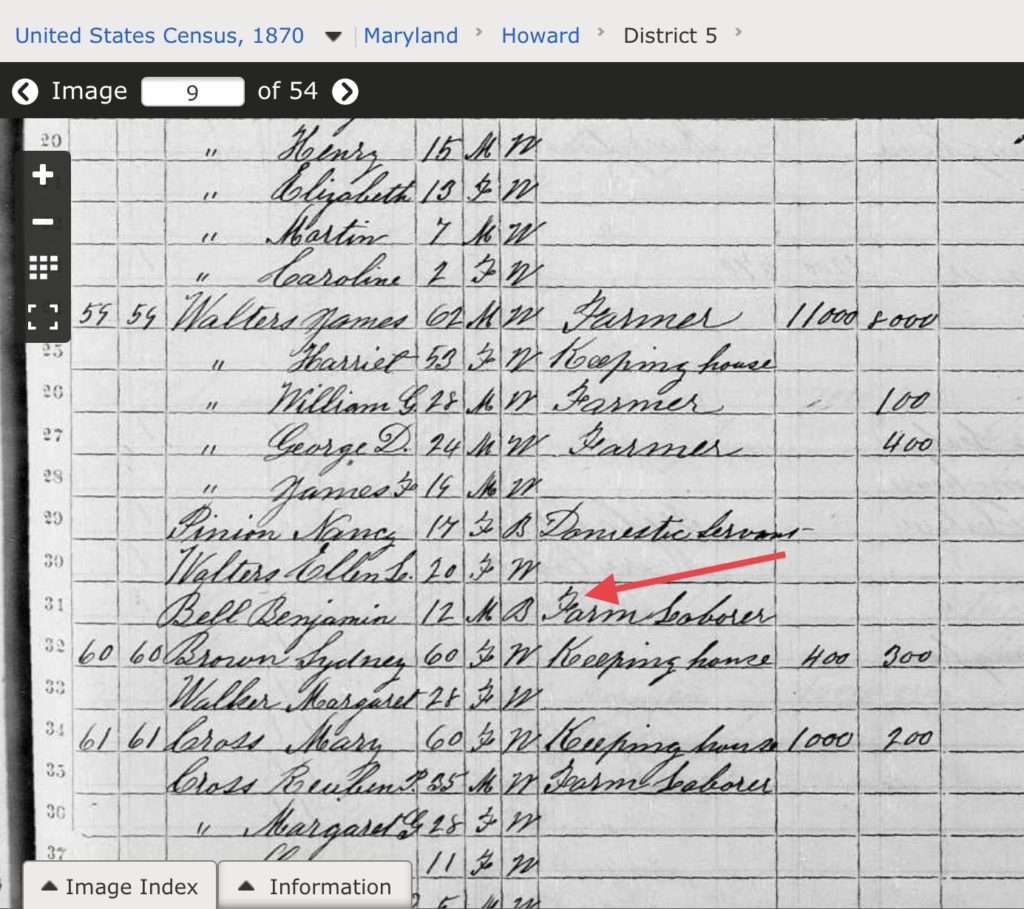

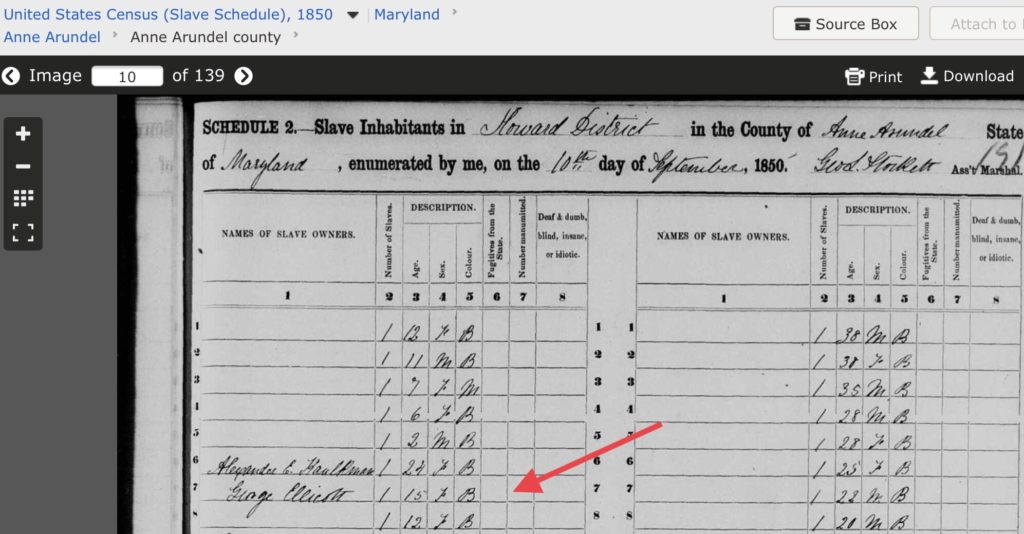

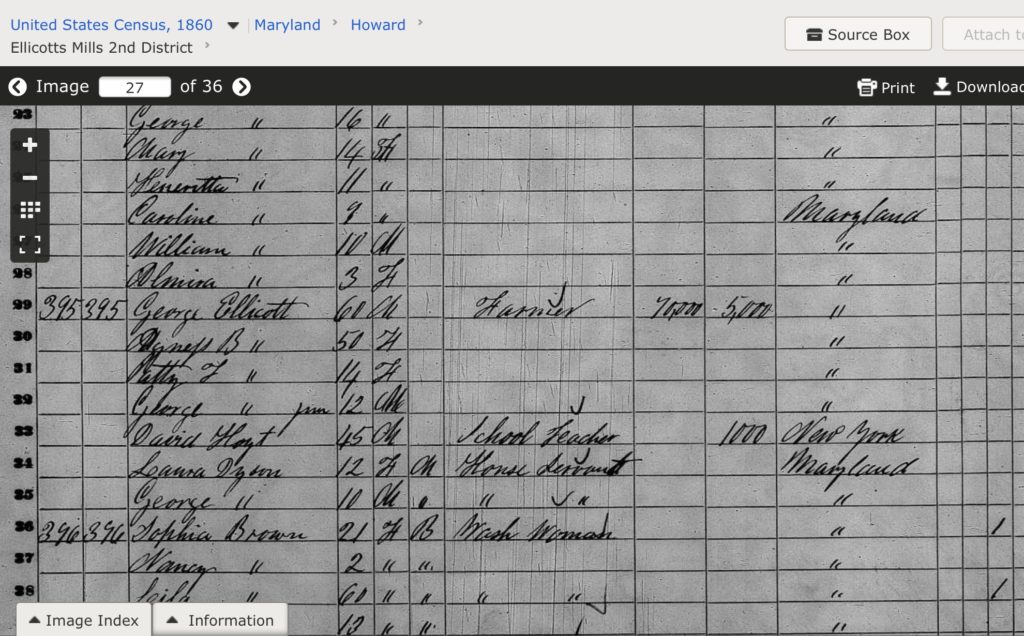

Was it the father or the son who was associated with the case involving Caroline who was sitting in jail on Christmas? George Sr. had been enslaving two young girls, ages 12 and 15 in 1850, according to the census image above.

60 years old by the 1860 census, George Sr. lived with his family and 12 year old son George, as well as 2 mulatto “servant” children (George Dyson, 10, and Laura Dyson, 12) in district 2 of the county. So, it wasn’t the younger George Ellicott associated with legal proceedings against Caroline. It isn’t known if the 2 servant children were the ones who Caroline allegedly enticed to run away from George.

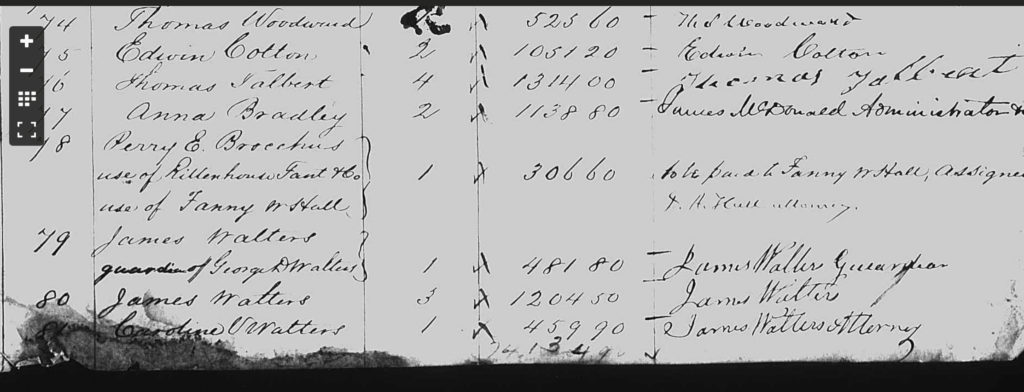

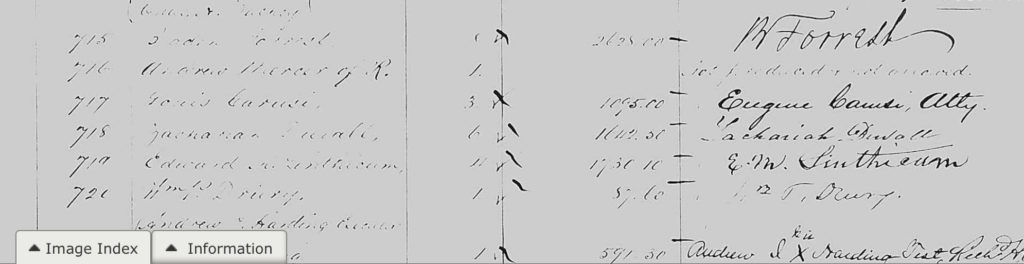

Caroline got released on what is now referred to as bail in the amount of $100 the day after Christmas. Joshua B. Davis posted the security for her appearance, and the State’s Attorney agreed to her release.

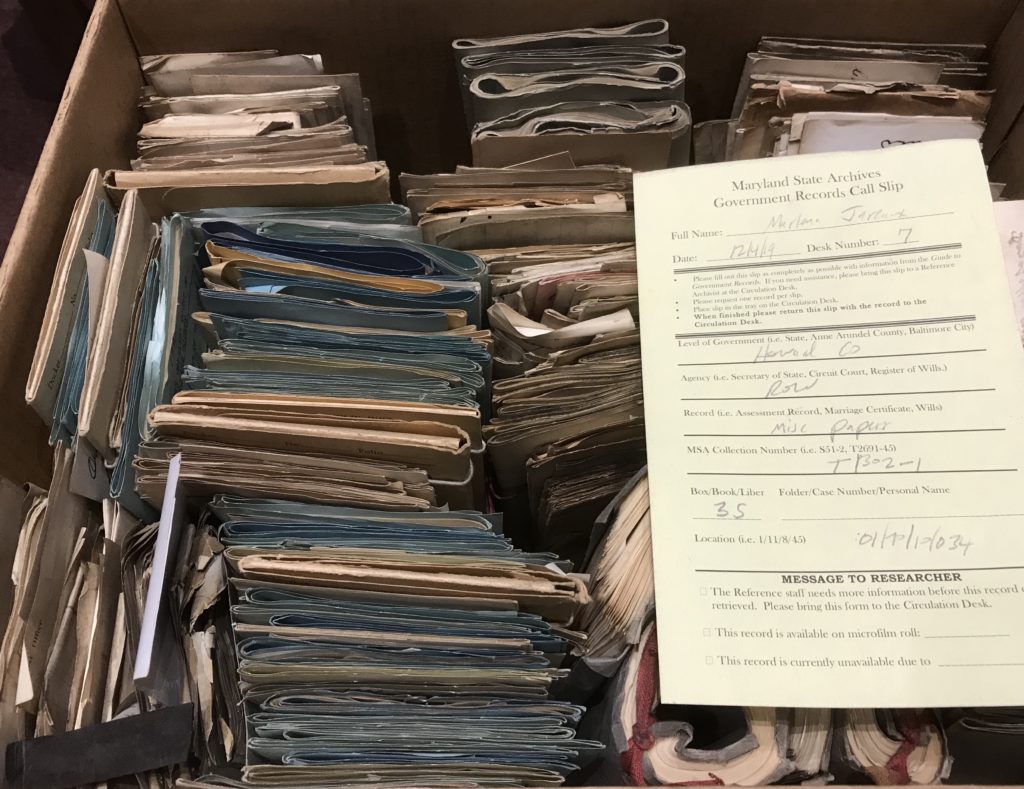

Here is the cover of the VERY old book I found Caroline and others in, down at the Maryland State Archives in Annapolis this past September.

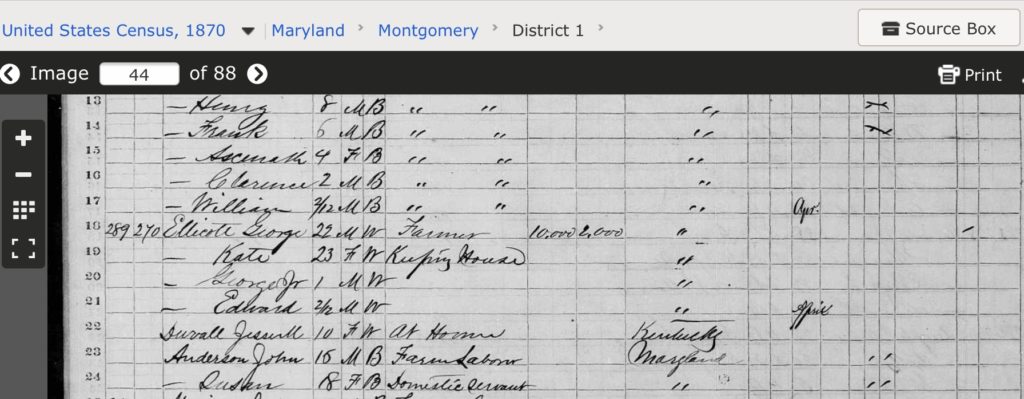

I don’t know (yet, thanks to COVID-19 closing things again) what happened in her case when she went back to court in March 1864 as the Civil War still continued. I only know that her son John (16) and daughter Susan (18) were listed as living with George Ellicott Jr (then 22 with a wife and son they named George) in Montgomery County in 1870 when the war had been over years ago. I can only imagine why, and I hope it wasn’t a punishment of some sort for Caroline.

I think it’s quite natural to encounter stories like this and ponder about what you’d do if it were you. The reader can probably accurately guess whether this author would have been like Caroline, in jail on Christmas of 1863. I raised my glass this holiday and toasted to finding this part of her story, and to the year ahead working with and in the community to unveil more.

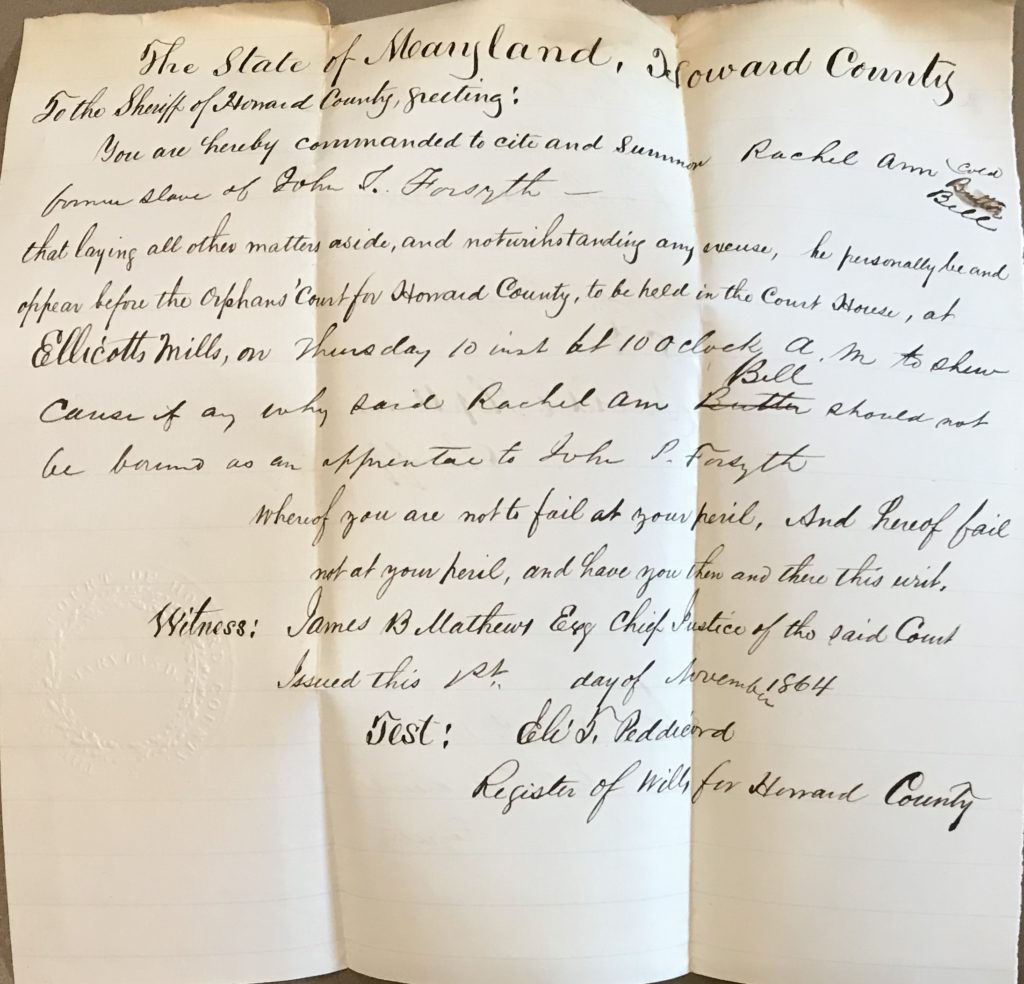

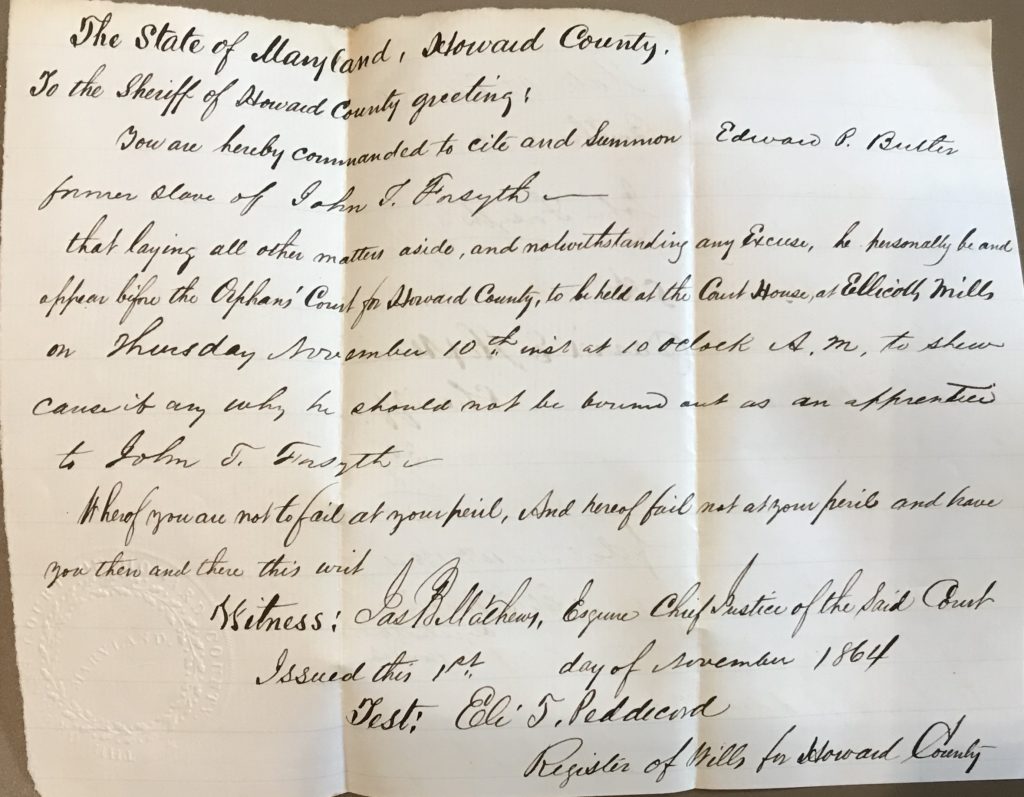

NOTE: Caroline’s children weren’t the only ones to face Orphan’s Court proceedings regarding being bound out to another family. As an example, the Howard County sheriff was told to summon Rachel Ann Bell to the Orphan’s Court in order to testify as to why she shouldn’t be bound out as an apprentice to John Forsyth. The date was November 1, 1864, and Rachel Ann was listed to be the “former slave” of Forsyth’s.

The sheriff was told to do the same to Edward P. Butler, also listed as a “former slave”. November 1st was the day that Maryland’s new state constitution banning slavery went into effect.

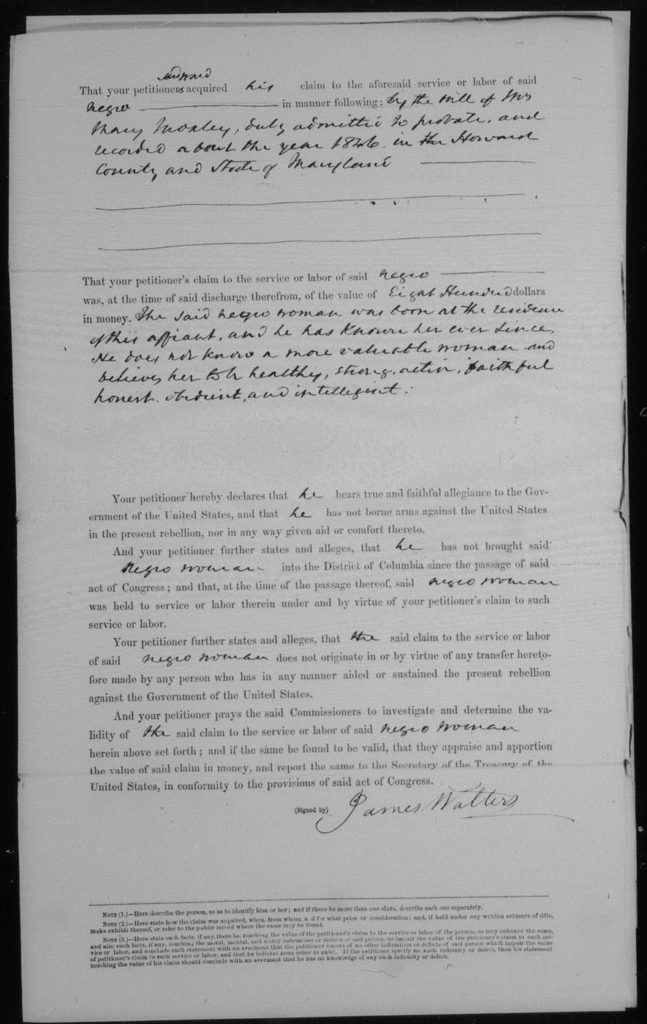

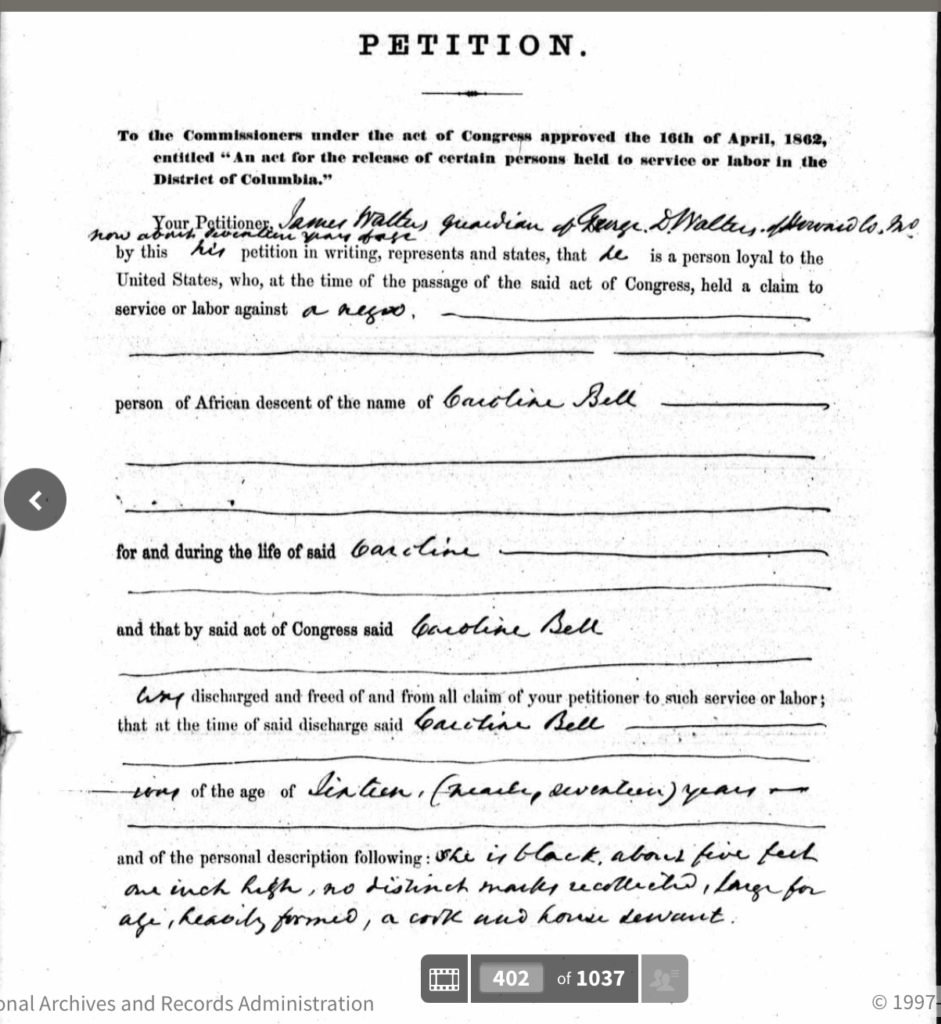

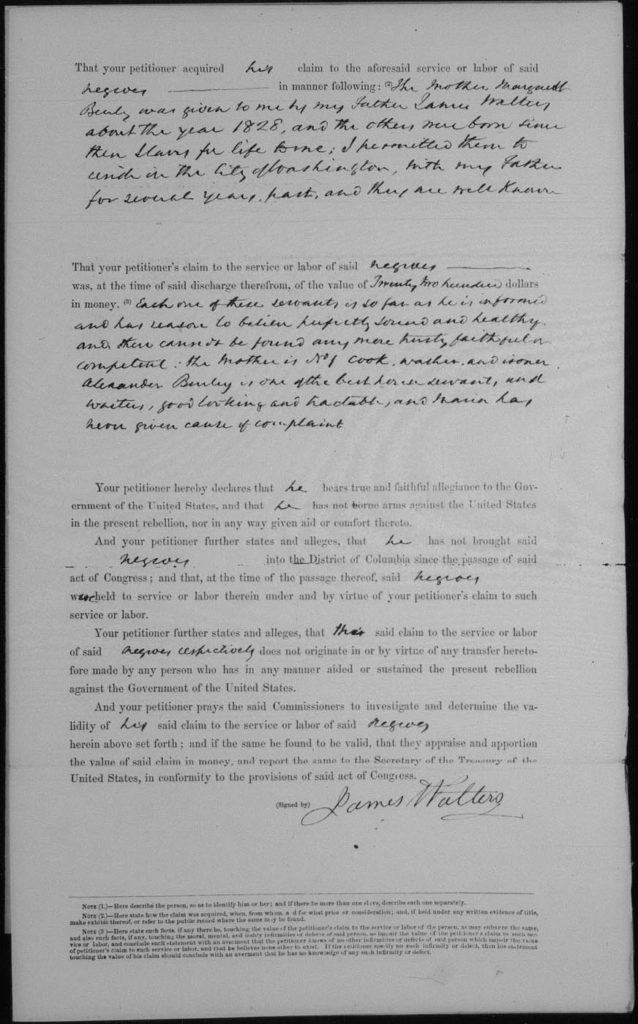

Rachel was only 16 years old when the Orphan’s Court summoned her to come. Richard was only 7. This is known because of the information Forsyth gave to Howard County’s Commissioner when he placed his name on the list of those wishing to be compensated for the loss of those they had enslaved being freed. (See the image on page 45)

Marlena Jareaux