The phrase “hard history” isn’t new, and the reason I’m using it for the history time period I primarily focus on is probably obvious to many. It’s things that are hard to think about considering the 2023 lives that many people have. Whenever you’re the person doing this type of work, you often hear things of soft protest like “No one here was alive during that time so why does this matter?” or “Why stir things up with this history?” As I’ve told people, the protest here in Howard has progressed to people warning me that the recent examination into Charles E. Miller for the local public spaces commission I co-chair was going to bring “some heat.” My personal favorite thing was being told that two white women who are county employees seem to enjoy referring to me as “the Black devil.” The words of my white mother’s reminder always help me in these situations: “they meant it for evil, but God meant it for good.” I’m certain that I’m called worse, and it says far more about them than it does me. They’re obviously uncomfortable with what the realities of accurate local Black history mean for all of us, since it often actually reveals the generational inequities that existed between many white and Black families. If you were forced to work for someone to effectively help them build generational wealth for their family, you understood what you were likely never going to achieve for yours (and you adjust). I’m talking about slavery and also many of the forced apprenticeship contracts of free Black children, by the way. Fast forward to the time of Charles E. Miller and some of the men of his time who were early developers in our county. How do you think it felt for Black residents who lived here who saw him get appointed to fill a public county commissioner seat while he was creating a development in which property would be sold that restricted the “lot and any part thereof shall not be used, occupied by, or conveyed to a person, or persons, of Negro descent or extraction”? Yes, he was a man of his time, and yes everyone here didn’t do it. The question for the reader is, how do you think Black residents and prospective residents felt about it in the late 1930s and 40s?

I get it that I do history differently here. That seems to bother some people who have done history different from the way I do it. I get calls and texts from people sharing the words written by those they see who dislike me doing history this way. I have always examined things from the perspective of the humans who were/are involved, and approach things from an anthropological standpoint which tracks to my schooling. I also examine systems to try to understand why things were created and what they depend upon in order to exist and function. I really like how that makes me different from them, and it has so far led to my discovery that Frederick Douglass spoke in our county, the discovery of the oldest Black church of our county, and the creation of the Roundtable research initiative which discovered the true Black origins of the log house that residents and visitors have oohed and aahed over for decades.

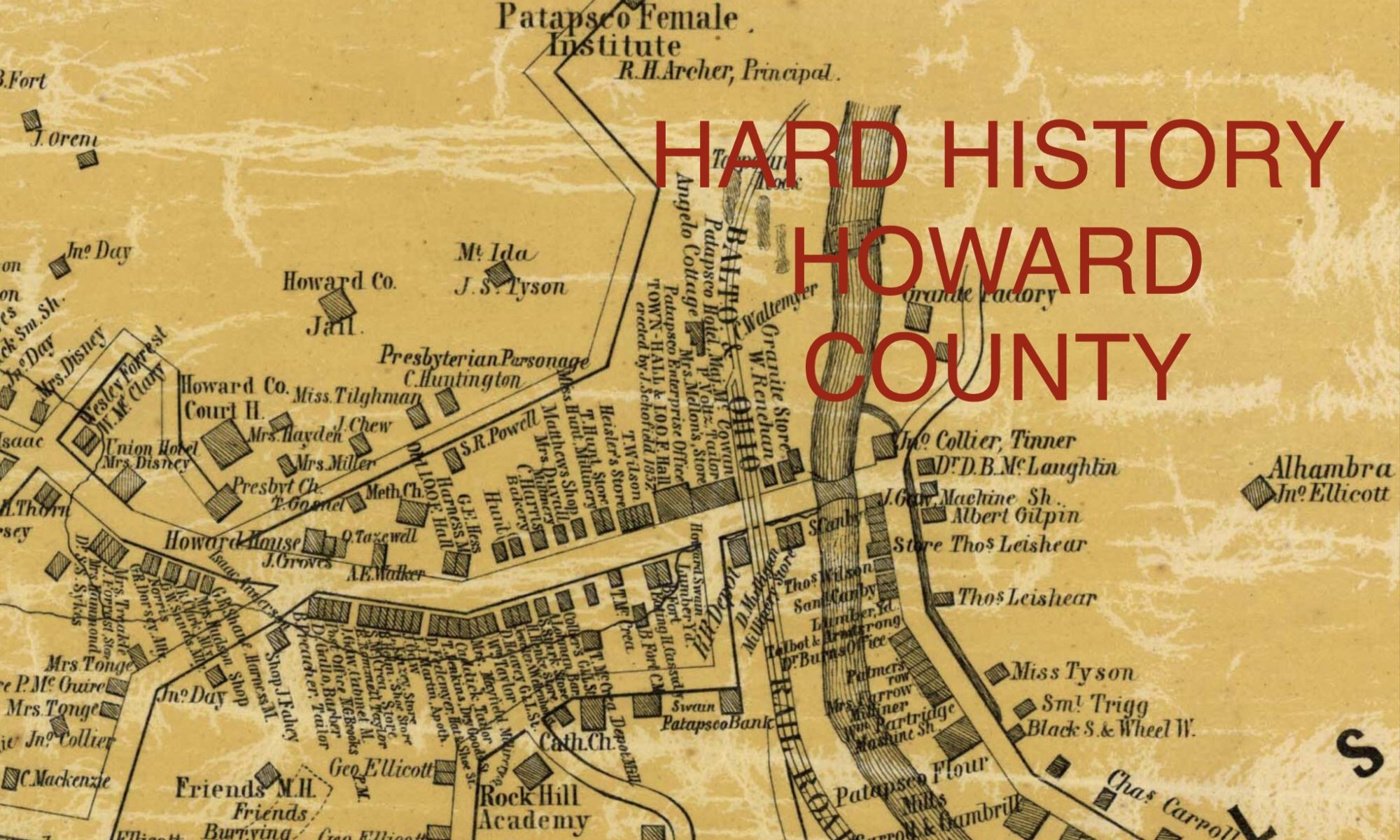

A social media post was brought to my attention a few days ago, and I wanted to bring attention to it here. A local for-profit tour company was posting about it, and I really appreciate seeing history involving Amos Matthews who was in the US Colored Troops being showcased. In a store window on lower Main Street Ellicott City is this display with a framed piece:

I don’t know who created the display, but I do know that they have it wrong and I’m fairly certain I know why. The creator focused on the newspaper report of Amos being drafted. In the picture I can see the blow-up of the newspaper with Amos and James Treakle’s names. Amos is listed as a slave of Treakle’s. Was he though?

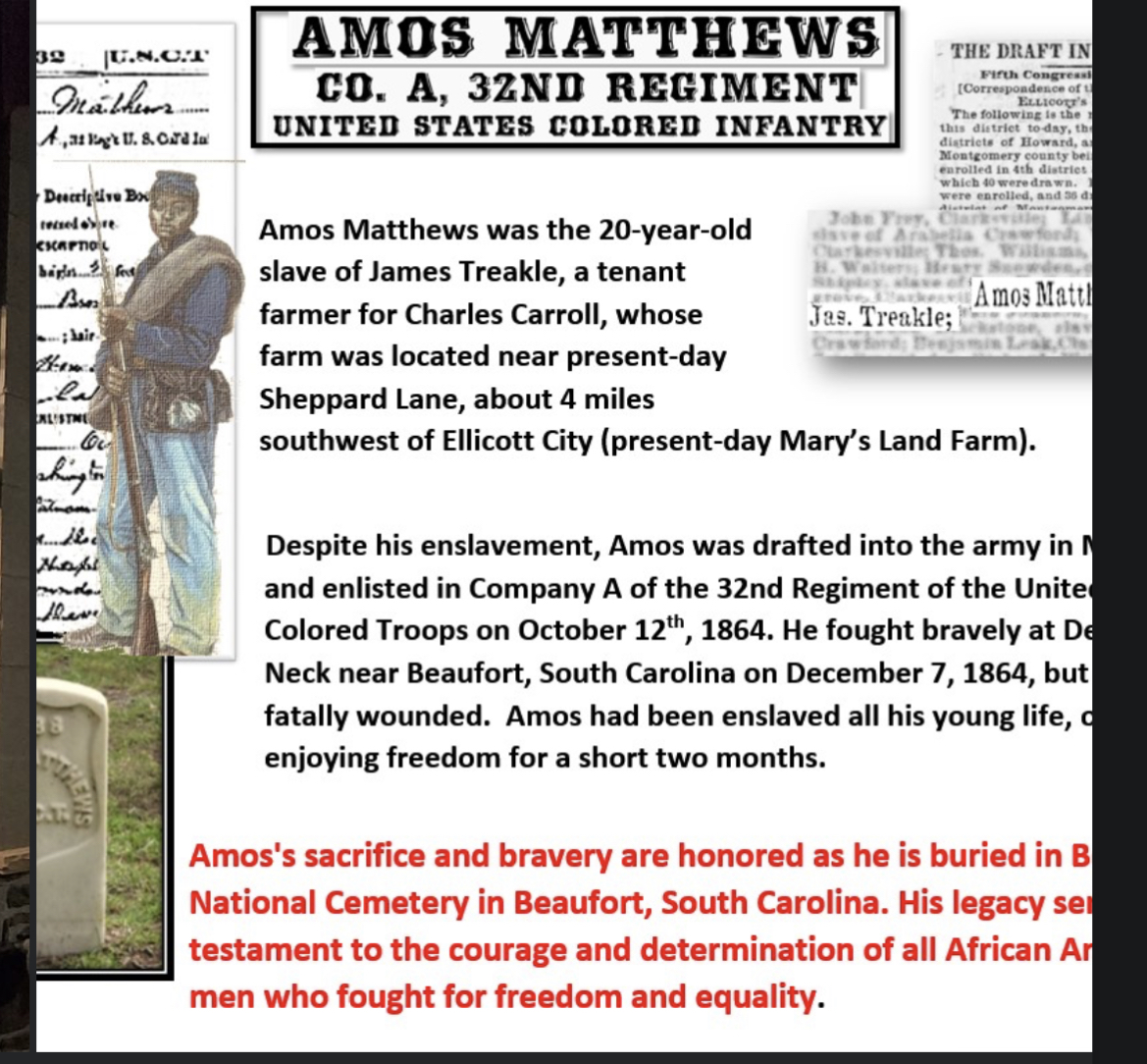

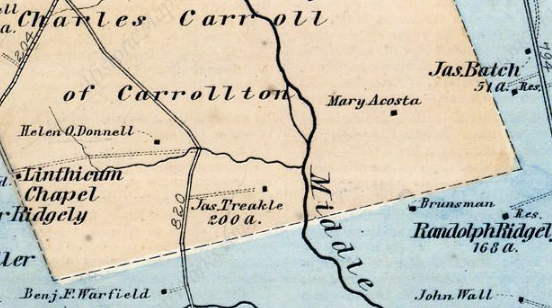

First, I’m not certain that Treakle was a “tenant farmer” of Charles Carroll’s on Doughoregan Manor. That Charles was the grandson of the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence Charles. Yes, there were several white tenant farmers who lived on his property through the years. But Treakle, who was NEVER a “commissioner” as has been inaccurately said about him (he was a justice of the peace for quite some time, and he or his father was a constable in the early 1830s), was listed to be the owner of quite a bit of real estate on the 1860 census. Was he a white tenant farmer of Colonel Carroll’s who was under an arrangement to pay for the taxes for the property he and his family paid rent for? Perhaps, but surely records would reveal that. I’d like to know, since it provides an interesting dynamic to history interpretation of census materials if it’s true.

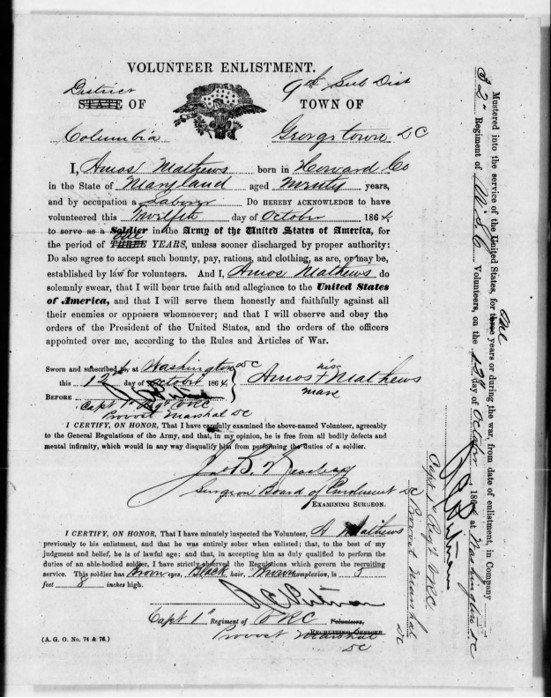

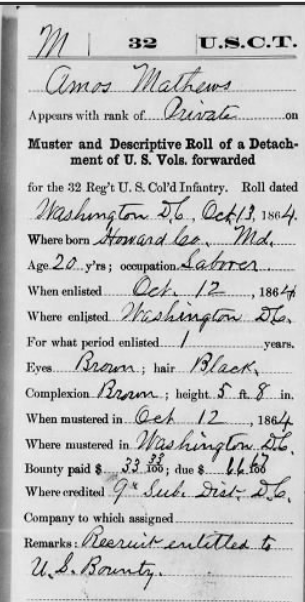

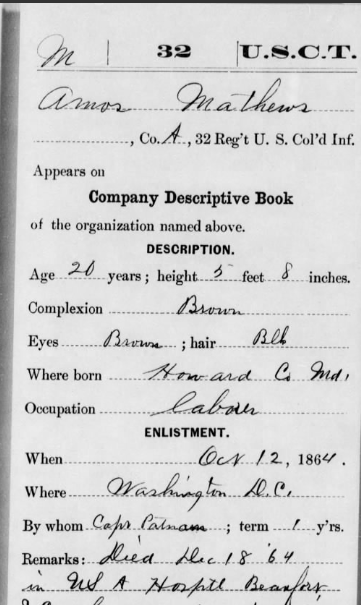

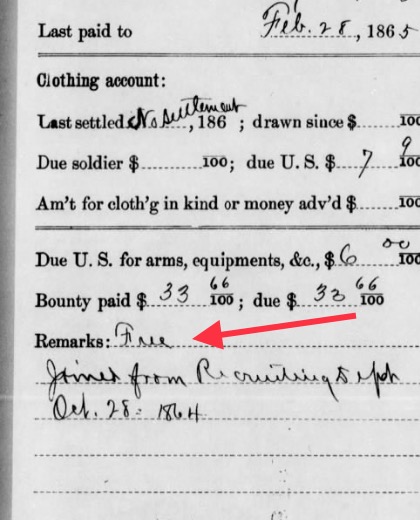

Getting back to Amos, the true focus of this post. The display reads “Despite his enslavement, Amos was drafted…” and I’m going to pause here. From his service records, you can clearly see that Amos volunteered for military service when he enlisted at Georgetown, DC on October 12, 1864. Twenty year old Amos was 5 foot 8 inches with a brown complexion, and he signed up for one year of service. He was also paid a portion of the bounty he was entitled to, which you didn’t get if you were enslaved. I can see that also on his service record. On another record, he was noted to be “Free”. See for yourselves…

I suspect I’ll be labeled a “Black devil” for wanting this history to be accurate for every person walking down Main Street in Ellicott City for the remainder of Black History Month. For those who have already seen it, you now have the accurate story about Amos but there’s more. Yes, he did have a short time in the military and did die and is buried in South Carolina. No, I don’t think it true that “Amos had been enslaved all of his young life..enjoying freedom for a short two months” from what I have. Treakle didn’t put his name on the list of enslavers who wished to be financially compensated after slavery was abolished, nor did his heirs. But I can tell you something about people I suspect were family members of his who had an experience with Treakle while Amos had gone off to fight in the war, if you want to know.

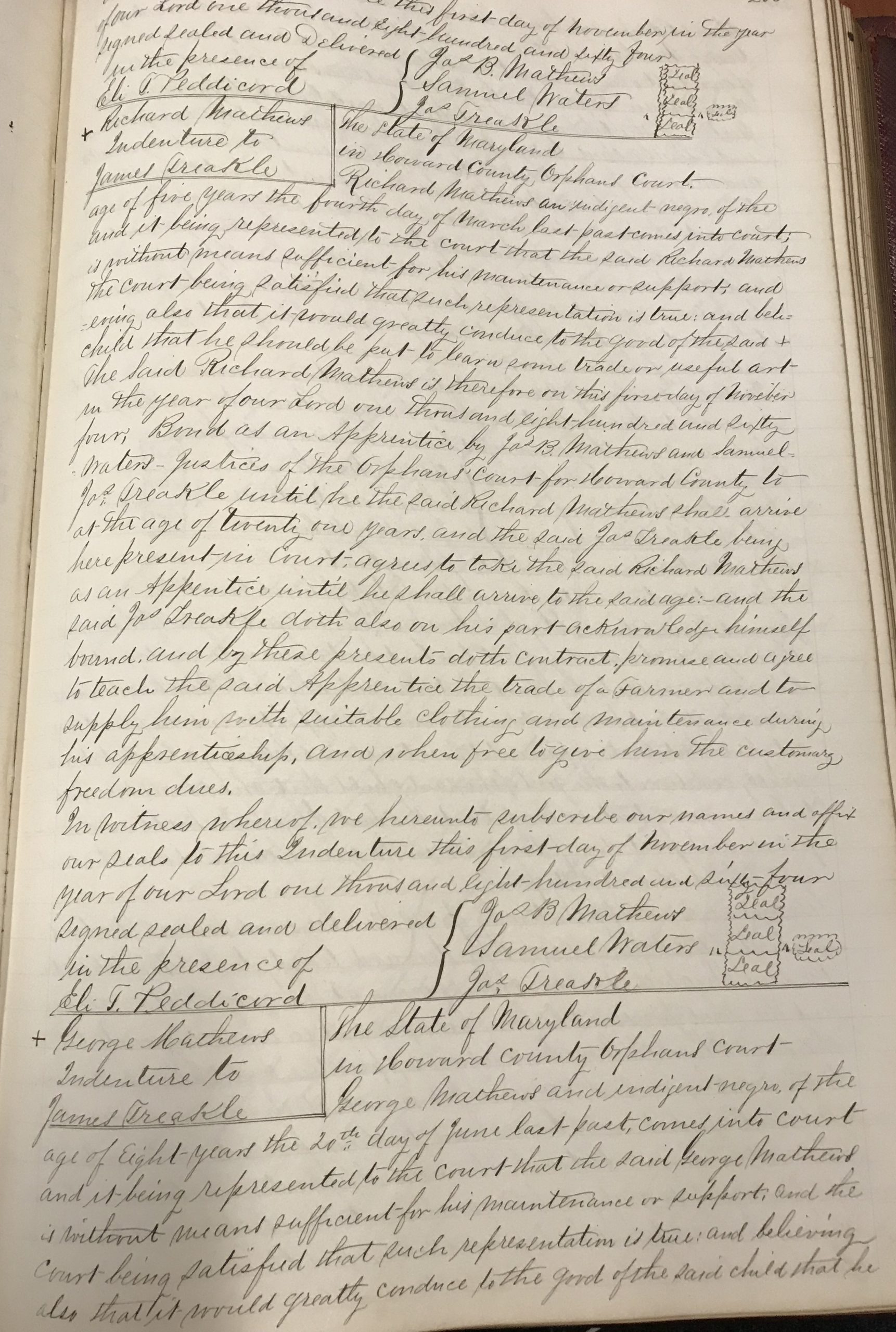

Elizabeth Mathews, age three, was indentured by the Howard County Orphan’s Court on the day that the state’s new constitution abolishing slavery went into effect. She was to learn to be a housekeeper, and serve in that capacity for Treakle’s family until she reached age 18. So was Henrietta Mathews, age eight MONTHS, and Alice who was six. Richard who was five, was to be his farmer until age 21. Here is his indenture contract, along with the first part of George Mathews’ who was eight years old:

Whose children were they? I’ll tell you that another day. When the 1870 census got done, Treakle was reported to own $10,000 worth of real estate. The census taker also recorded four young Black girls in his household and one was “Alice” who was about the same age as the Alice apprenticed to Treakle in 1864. I don’t know if it’s the same Alice, nor do I know (yet) whose very young children they were.

This would have been prior to Treakle’s official purchase of part of Doughoregan Manor which was recorded in 1878 (book 38 page 651). James’ four sons would receive the property from him in 1881 before he died (book 43 page 216). The names of two of his sons (Emmett and Albert Treakle) can be found on the Confederate memorial housed by the Howard County Historical Society, Inc.’s museum. They fought on the opposite side of Amos. How do you think Black people felt about that? Here’s the Treakle land at Doughoregan, shown on the 1878 Hopkins map and on a drawing made for a Carroll family lawsuit involving the division of the land being fought over:

Were there Black people forced into enslavement on the property belonging to the descendant of the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence? Absolutely! Stories for another day though. Today was for a line of the Mathews family.

Marlena Jareaux