When I moved from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Howard County in 2010, my children were in the 3rd and 1st grades. I was excited to find a community that was so diverse that the elementary school had no racial majority. This was a radical departure from the nearly all-white community in which we had lived on Cape Cod. While the middle and high schools my children attended were also highly integrated, I noticed as they advanced through the grades that there was mounting academic and social segregation.

I stepped forward to be a Troop Leader for my daughter’s Girl Scout troop when the girls were rising 9th graders. It was a fantastic group of girls that had been together since elementary school. The racial make-up reflected the diversity of our community: African American, African, Indian, Korean, and white. This was the fall of 2014, which was a time of a growing racial unrest sparked by the killings of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and so many other Black people. We had a lot of conversations about racism that year, and the girls decided to do a group project in which they conducted a survey to understand attitudes about racism. The data they collected pointed to a harsh reality of the world we live in: many respondents who self-identified as white did not acknowledge that racism was an issue. At the beginning of their high school careers, this was shocking to most of the girls, and they wrestled to understand how it could be and what they could do about it. By their senior year, the litany of racist comments and behaviors they had observed or experienced during high school was a long one.

In 2017 The Baltimore Sun published an article about racial segregation in the Howard County Public School System. Although Howard County is among the most integrated in Maryland, enrollment data showed that advanced classes were disproportionately White, while grade-level and remedial classes were disproportionately Black. The article was grounded in data the Sun had collected and analyzed, and it focused on two high school students, Mikey Peterson, who is Black, and Eli Sauerwalt, who is White. Their different experiences at the same high school, and the way those experiences impacted them, highlighted the real harm that the system was perpetuating. I know Mikey, and I felt an intense mix of emotions when I read the story. I was so proud of him for his bravery, and I was so sad that this had happened to him. Nearly four years later, I remember that Sun article – not because of the research and data analyses – but because of the stories.

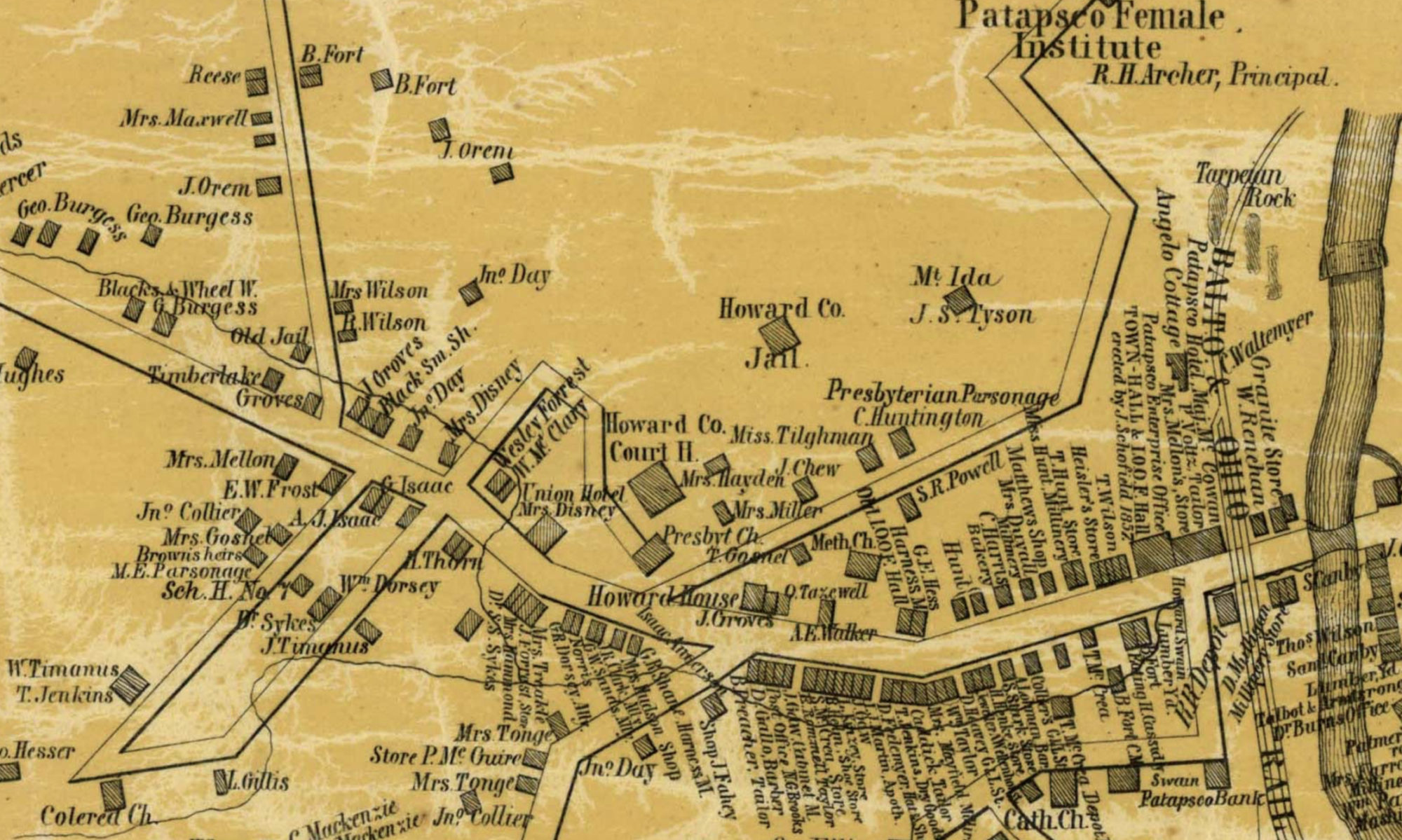

When I read the Sun article, I understood the inequities to be a legacy of our nation’s white supremacist roots. This is true, and yet… we have our own unique history in Howard County. What are the forgotten stories that help explain the current state of racial disparities in our schools? How much wisdom have we collectively lost because we systematically choose – over and over again – not to honor and value the lives and vibrant communities of Black and Brown people?

Historians wield enormous power. They interpret the meaning of events and circumstances by selecting which facts to include and whose perspective informs the narrative. The culture of white supremacy on which our nation was constructed has shaped the stories we learn about our history. This must change.

Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative have issued an insistent call to remember our nation’s history of sanctioned violence. More than 4,400 African Americans were lynched between 1877 and 1950. While the sheer magnitude of these atrocities is unfathomable, learning the stories of those whose lives were violently ended connects us to their humanity, and perhaps to our own.

Three men, who experienced lynching or near-lynching in Howard County, lived rich and meaningful lives:

Rev. Hezekiah Brown

Nicholas Snowden

Jacob Henson, Jr.

In remembering these three men, Howard County Lynching Truth & Reconciliation seeks to restore their humanity and honor their lives. This is an essential step to repairing the harm that continues today.

Rev. Hezekiah Brown’s story highlights our long history of choosing not to equitably educate Black children in Howard County. The present-day inequities written about in The Baltimore Sun are not new. They are connected to stories – mostly forgotten – from our past.

I feel so grateful to be part of the founding group of Howard County Lynching Truth & Reconciliation.